Photo illustration by Dami Mojid / THE REPUBLIC.

the ministry of arts / books dept.

The Language of Violence

Photo illustration by Dami Mojid / THE REPUBLIC.

the ministry of arts / books dept.

The Language of Violence

I f indeed there is a perfect metaphor for everything, then the perfect metaphor for journaling would be a bridge—that is, a bridge between our inner world and our external reality. Its transformative though quiet roles in our lives seem so endless as the reach of the imagination. It does not only shape our understanding of self—a way of processing our experiences, emotions and trauma—but also stands in as a repository of our personal history and cultural memory, our dated entries also anchoring private happenings in broader historical contexts. In the South African poet Qhali’s hands, in her debut short collection of poems titled Crying in My Mother’s Tongue: Ukulila, poetry becomes a refined, distilled form of journaling. The book is a startling and thorough exploration of language and identity, intergenerational trauma and healing, sexual violence and culture, motherhood and family relationships, each as complex as it is illuminating.

LANGUAGE, FORM AND MEMORY

‘Daughter’, the poem that opens the book, is an ars poetica, introducing key themes that recur throughout the collection: the interplay between memory and the present, the duality of experience, the body as a site of stories, the search for maternal connection, and the smooth movement between worlds and languages—namely English and isiXhosa. Functioning also as a manifesto for how the rest of the collection will operate, the poem begins with the expressive intention of the poet:

there are corridors in my memory

i shall now take you into

dark rooms in which i am blind and see everything

where big hands pin me down

feasting on me dead breathing

where my blood becomes the venom

where no one saves me

Beyond intimating the dark recesses of her paradoxical ‘blind’ memories—memories she both resists and cannot escape—Qhali finds an adequate language, both emotional and critical, for expressing rape and gender-based violence. One of the first poems that showcases her gift for compression is her first journal entry dated 17 January 1994, titled ‘The Pregnant Tree in Our Village’. If ‘this [Ukulila] is the story of a woman / moving between time / between worlds’, then the two characters in ‘The Pregnant Tree’—the mythical Mamorena, mother of kings, and the speaker—embody the universal, historical realities of women across times: from the inevitability of gender-based violence to the necessity of resilience. Mamorena, for instance, is punished by the gods for what is out of her control in the death of one of her ‘six kings’ or sons:

one died on her back

three months old and where he died

a pregnant tree pushed out

right from the center of her back

These two poems, ‘Daughter’ and ‘The Pregnant Tree in Our Village’, serve as introductions to themes developed throughout the collection. In the entry for 17 June 1994, titled ‘Dear Qamata, Why’d You Give Tata Small Hands’, ‘umama’ is a real-life allotrope of the mythical Mamorena who becomes a victim of the male ego of her husband:

tata’s hands are too small

to hold umama

so he cuts her up to make her fit

he cannot have umfazi

bigger than him living in his house

Rife with underlying critiques of the status quo, the phrasing of the poems are illuminatingly precise: ‘too small’ not only signifies the physical anatomy of ‘tata’s hands’, but also the smallness of his character. In the same vein, Qhali brushes off both the dismissive vice and the irascible folly of old men towards women young and old with the brusque force of a single, qualifying word. Its precise criticism reaches the heights of satire in the prosaic journal entry for 1 June 1994, titled ‘Dear Qamata, I Need to Pray with Makhulu Now’: ‘and tata says children must keep quiet when big people talk.’ Not old, not wise, but big people. Indeed, a mocking yet sufficiently economical clapback.

shop the republic

Another point of admiration is Qhali’s seamless movement from her acquired language of English and her native tongue of Xhosa. In the emotionally taxing poem, ‘I Am a Glass’, Qhali laments the seething pain of trauma and unrealized justice:

Ingono zam black monstrous chunks now My nipples

Intliziyo yam My heart

ibetha emaqatheni beat at my ankles

All stuck in this bottle with me

All charred pieces of flesh for the animal’s now

And I am stuck in this bottle

And he is out there

Smiling

To have gotten away with it

To have gotten away with it

Qhali’s code-switching offers a masterclass in artistic propriety: rendering these visceral phrases in isiXhosa amplifies their emotional weight, while the accompanying translations concentrate our attention on the immediate association between languages—deepening our understanding of the trauma being expressed.

Meanwhile, the memories recorded in the journals as expressed in the poems do not happen in a day as the dated titles suggest. Rather, each journal-poem represents moments so representative they become seared into the speaker’s memory firmly enough to remember the signifying dates. Using the journal form for expressing these private realities then becomes an act of transformation: as the private becomes the public, the personal is universalized. A survivor to be admired rather than pitied, Qhali emerges—through sharing her journal with the world—as someone who has drawn strength from articulating her trauma, becoming a proud embodiment of the strength that recovery demands.

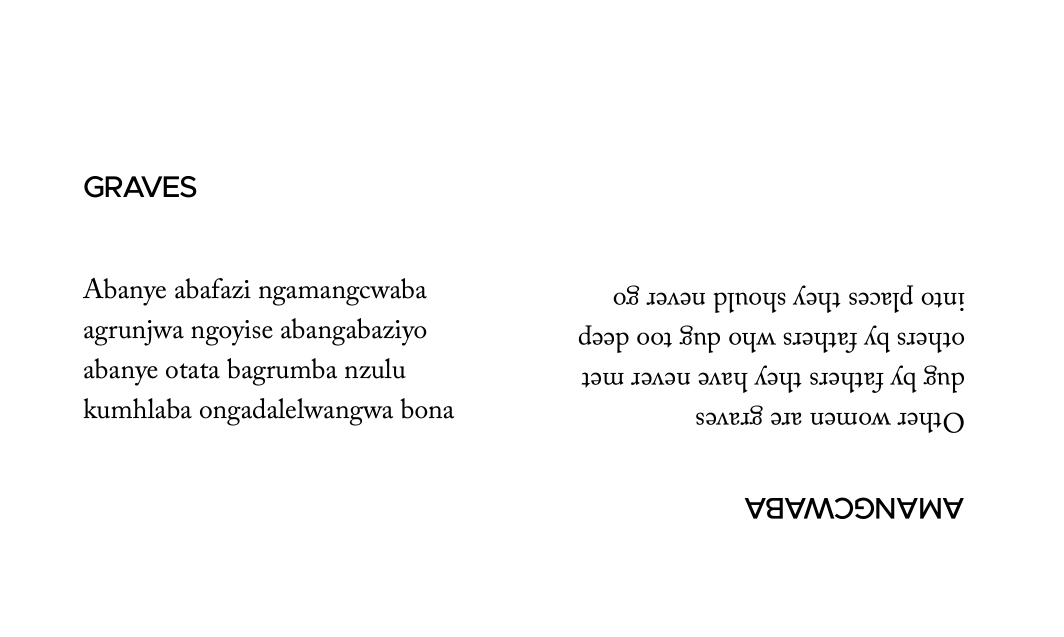

The animating impulse of the book lies in Qhali’s clear, precise and serious treatment of her interbreeding preoccupations—rape, self-doubt and silence, domestic violence and its generational toll, and the depressingly excruciating pain that results from these horrible realities—all rendered with a seriousness that transcends aesthetics. The short poem, ‘Grave’, is aesthetically smart—not only in how it channels emotional intensity through its dual-language structure, but also in how its visual form invites the reader to engage actively with its layered meanings. However, the form is even more interpretively functional: the poem is written in isiXhosa, but its translation to English is turned upside down just like the superindecent nature of the violence and incestuous act it attempts to reify. Even though the telos of the formal touch can be easily ascribed to the simplistic notion of literary finesse, the touch nonetheless reflects the shamefulness of familial rape as well as the poet’s congenital repugnance—earned as much from nature as from experience—to such human turpitudes:

shop the republic

BREAKING THE SILENCE OF VIOLENCE

In her chef d’oeuvre, a seven-page poem called ‘A Dying’, Qhali strips her language bare of poetic subtleties to recount a harrowing moment of rape, made even more horrifying by the presence of the speaker’s child sleeping in the next room. In the poem, nothing is left to euphemism as everything is given to dysphemism:

The man on top of me grunting pulls his penis out of his pants

A breathing snake falls onto my stomach

God is quiet

He hits me with it His penis

I want to ask him to take everything

Everything I no longer care about

But I don’t move

I don’t speak

God is quiet

This is helplessness

Qhali’s precursors in this tradition, in both form and substance, range from Frank Chipasula’s ‘Manifesto on an Ars Poetica’, Susan Kiguli’s ‘I Am Tired of Talking in Metaphor’, Adrienne Rich’s ‘Rape’, June Jordan’s ‘A Case on Point’, Sylvia Plath’s ‘The Jailer’ to, in recent memory, Patricia Lockwood’s ‘Rape Joke’. However, Qhali does not only contribute to the tradition, but she also advances it through her uncompromisingly explicit language that serves as criticism of both sexual violence and our societal reluctance to confront it directly.

Perhaps unconsciously, but for Qhali, the explicit language is a more exacting criticism of rape and gender-based violence than the subtle vilifications found in self-precious poetry. It not only disturbs but totally disrupts the pretentious decorum of the civilization that condemns language faster than it does with the terrible realities that the faulted language describes. For example, rather than engaging with Patricia Lockwood’s Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals—where the ‘controversial’ poem ‘Rape Joke’ serves as a provocative critique—the American critic Adam Plunkett dwells on the poet’s intention and her relationship with readers, a reading better suited to psychology than literary criticism. In the recent tradition of expressing sexual violence, language—and its discursively unconventional use that defies cultural propriety and social civility—serves as the sharpest critique of the tradition of silence that surrounds it. No one is protected from the terrible image and pain the tradition paints and instigates. Both the potential victims and predators are faced with the horrifying propensities of the world.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Neither selective nor coy with the roiling specifics of rape, Qhali intimates a profound sensibility untempered by the shaming reactions of our ‘civilized’ society to rape. However, the true object of Qhali’s unapologetic critique is the pretence of civility itself, which she exposes through the raw language of sexual violence, an expression equal in severity to the depravity society and its worst inhabitants are capable of. While understanding prudishness is often an ironic enemy of the truth, she does away with it in what reads like a personal revelation. There is no respect for decorum in Qhali’s poems, because to do so is essentially to reassume the quiet and docile roles once played by past victims of rape. ‘Now as before,’ says Germaine Greer in The Female Eunuch, ‘women must refuse to be meek and guileful, for truth cannot be served by dissimulation.’ To be offended by Qhali’s naked diction is to confirm the irrational reality that language is easier and more often gatekept than the concrete evidence of what that language represents. Qhali’s explicit language is not intended to be obscene but rather to challenge the dismissive attitudes we often have toward the darkest realities. In doing so, she aligns with Greer’s call for truth to be spoken plainly. Through her poetic lens, these realities cannot be easily dismissed, demanding that we face them directly.

In a subtle manner, Qhali criticizes ‘God’ and ‘Qamata’, the Xhosa equivalent of the Christian God or the Islamic Allah, for their passiveness to her historical plights as a woman. Despite the withering experience and the divine silence that isolates her, she bounces back, with Tsolobeng (the poet’s place of birth)—mentioned only five times throughout the book—serving as her space of peace, safety and recovery. For Qhali, Tsolobeng is ‘where truth and sanity / wait in whispers.’ An exemplar of an inevitable poem, ‘Tsolobeng’, which closes Crying in My Mother’s Tongue: Ukulila, stands out because it is everything from unexpected to shattering, shifting from shock to hope. It embodies the openness to healing and prosperity, and the possibility of contentment. This sense of possibility on the other side of gruelling experiences is what Qhali has given us in Crying in My Mother’s Tongue: Ukulila—her poems, together, encouraging us to carry this possibility home with us. Despite its emotional and gut-numbing preoccupations, Qhali’s book is hardly one of yearning because the speaker understands that what she longs for the most, especially healing, is not out of reach; it is in Tsolobeng, waiting to be claimed⎈

CRYING IN MY MOTHER’S TONGUE: UKULILA

QHALI

41 PP. AKASHIC BOOKS, DECEMBER 2024

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page