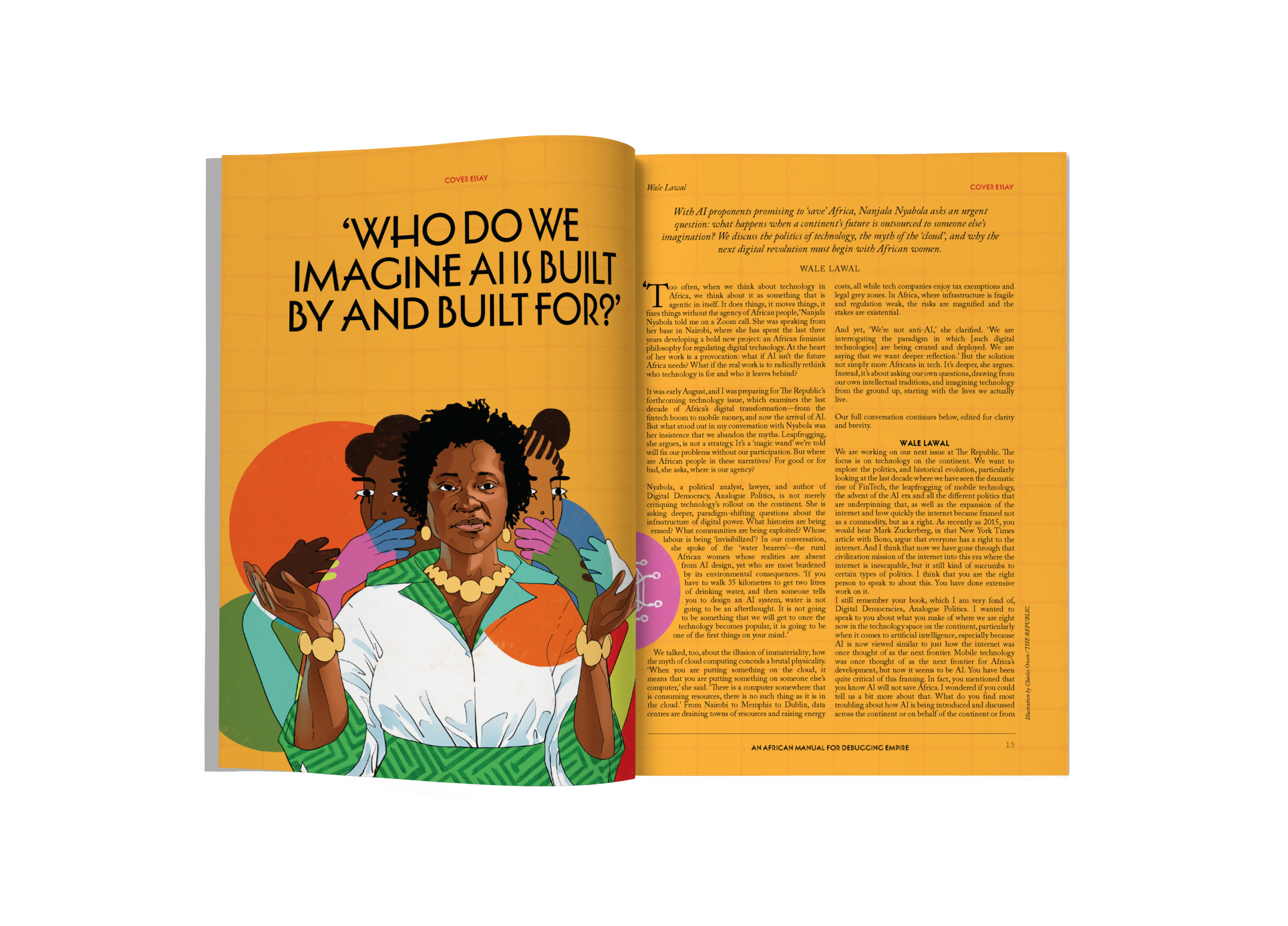

Photo illustration by Dami Mojid / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref 1: Swearing-in ceremony of President Brice Nguema, Libreville, 2025. PAUL KAGAME / FLICKR. Ref 2: Omar and Ali Bongo. / EU, FOREIGN OFFICE.

THE MINISTRY OF POLITICAL AFFAIRS / DISPATCH FROM GABON

The Recalibrated Presidency of Brice Oligui Nguema

Photo illustration by Dami Mojid / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref 1: Swearing-in ceremony of President Brice Nguema, Libreville, 2025. PAUL KAGAME / FLICKR. Ref 2: Omar and Ali Bongo. / EU, FOREIGN OFFICE.

THE MINISTRY OF POLITICAL AFFAIRS / DISPATCH FROM GABON

The Recalibrated Presidency of Brice Oligui Nguema

On the evening of 30 August 2023, Ali Bongo, Gabon’s outgoing president and former presidential candidate in the 26 August 2023 general election, was deposed and placed under house arrest by the Committee for the Transition and Restoration of Institutions (Comité pour la Transition et la Restauration des Institutions; CTRI) following the release of seemingly fraudulent results by the elections council. The fall of Ali Bongo marked a seminal turning point in Gabon’s history—ending a long dynastic reign by father and son.

President Brice Oligui Nguema has since swooped in as the country’s new strongman, vowing to rehabilitate the dignity of the Gabonese people and restore the institutional integrity of the Republic, perceived by most as having been undermined by the authoritarian tendencies of the former regime. The Gabonese—hostile to the ideology of the formerly dominant Gabonese Democratic Party (Parti Démocratique Gabonais; PDG)—had accordingly called for its dissolution en masse. But while the final report from the Inclusive National Dialogue of April 2024 recommended its immediate suspension and the ineligibility of its cadres for post-transition elections, Nguema balks. Instead, Nguema appears to be working to re-legitimize the party by appointing several executives from the fallen regime to important positions in the politico-administrative apparatus. This policy, contrasting a priori with the aspirations of many Gabonese, is nevertheless part of the new president’s agenda and policy of inclusion that he has been advocating for since taking power. But his proximity to the former regime raises questions. Is Nguema’s presidency really a political break or is it rather a restyled continuation of the Bongos?

NGUEMA AND GABON’S REGIME CHANGE PROJECT

To contextualize the political, institutional and constitutional changes underway in Gabon (including both institutional restoration and modernization of state projects), it is helpful to recall the foundations of the Bongo regime and the factors driving the coup d’état of 30 August 2023.

The Bongo Regime: Core Foundations and Factors of its Collapse

For over half a century, Gabon was ruled by the Bongo clan—a regime that has largely managed to maintain itself uninterrupted due to its ability to adapt to contemporary developments and maintain the strengths of its main pillars. The first pillar is the personality of Omar Bongo, who shaped this regime and embodied Gabonese political life to the extent that his name is often still confused or conflated with Gabon today. Most contemporary Gabonese elites emerged from this regime, while others are closely linked to it through the positions they held. This applies to President Nguema, who was formerly head of the Republican Guard—the second pillar of the regime. Composed principally of nationals from Haut Ogooué, a stronghold of the regime, the Republican Guard is reputed to be the most powerful among the country’s security and defence forces. Created in the aftermath of the abortive coup of 18 February 1964 to ensure the personal security of President Léon Mba, it gradually became the armed wing of the Bongo regime. Its main objective is to prevent any desire for regime change in the country. The last and perhaps most important pillar is the PDG. Once a single party with deep-rooted connections across various elements of the state, the PDG has remained in power thanks to the ‘parodies of presidential elections,’ as characterized by Professor Joseph John-Nambo, and the selective incentives to ensure the loyalty of local elites. But beyond the official reasons—and following the aborted coup d’état of 2019—the coup of 30 August 2023 was the result of President Bongo’s state of health (weakened and under curatorship) as well as the divisive project of dynastic succession carried out by his wife in favour of Noureddine Bongo. President Nguema ascended to power in an environment where the institutions of the republic had lost all credibility; poor governance had become the norm, and the Gabonese were desperate for a change in regime.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00

Incomplete Institutional Restoration?

Among the main commitments made by Nguema on 4 September 2023 were: rebuilding the state; drafting a new constitution guaranteeing the rule of law, good governance and judicial independence; and organizing free, competitive and fraud-free elections. Unlike his counterparts in the Confederation of Sahel States (Confédération des États du Sahel), Nguema committed to a two-year timetable for the transition. Three reforms in particular deserve special mention.

First is the adoption, at the end of the Inclusive National Dialogue and constitutional referendum, of a new constitution approved by 91.8 per cent. Unlike in the past, this constitution enshrines democratic alternation by limiting the number of presidential terms to two, without any possibility of modification. Additionally, the constitution prevents any form of dynastic succession at the top of the state and enshrines the separation of executive and judicial powers through adjustments to the new regime to rebalance relations among the various institutions. But the construction of the rule of law desired by President Nguema necessitates real judicial independence, historically subservient to the fallen regime. This presupposes, as scholar Guy Bucumi reminds us, ‘a deconstruction of the fallen judicial order and the reconstruction of a new one.’ Unfortunately, the exfiltration of the Bongo family—despite suspicions of high treason and active corruption—reinforces the perception of a justice system that had been rehabilitated without being truly restored. These constitutional reforms also concern the nature of the political regime and the Constitutional Court, a body responsible for regulating institutions but often dubbed the ‘Tower of Pisa’ for its decisions that have often favoured the Bongos. The new constitution institutes a presidential regime to the detriment of the semi-presidential regime in force since 1991, but with few safeguards, fuelling criticism of a tailor-made constitution. The Constitutional Court—whose image has been tarnished by the validation of fraudulent elections—has also been subject to ‘profound restructuring’. However, long led by Marie Madeleine Mborantso, a close friend of the Bongos, it is now in the hands of Dieudonné Aba’a Owono, a loyal supporter of President Nguema.

Secondly, the process of restoring constitutional order was preceded by important reforms, in particular the dissolution of the Gabonese Elections Council, which was deemed responsible for the poor organization of elections by the military, despite them being co-managed by several institutions. It was also preceded by the strengthening of prerogatives by the Ministry of the Interior in the organization of elections and the adoption of Organic Law 001/2025 on the Electoral Code. The latter introduced several reforms: including the ceiling on electoral expenses, an obligation to post minutes in each polling station, the creation of an authority for electoral control, and referendums. In practice, Gabon’s presidential election of 12 April 2025 revealed significant resource disparities between candidates in the running. Several candidates said they did not receive public funding, despite this provision being enshrined in the new constitution. Nevertheless, despite fears of a democratic reversal, this election was an unprecedented experience in the country. The election of Nguema with 588,074 votes, or 94.85 per cent, according to the Constitutional Court, is not very surprising. Indeed, since the beginning of the transition, President Nguema has actively worked to neutralize his potential challengers either through appointments within the transitional institutions or through constitutional norms, making them ineligible for the presidential election. As a result, the election of 12 April was certainly open but not hotly contested.

Finally, as a prelude to the legislative and local elections of 2025, a bill on parties has been adopted. Adopted in the application of Articles 6 and 94 of the Constitution, Law 016/2025 of 27 June 2025 on political parties defines the new modalities for the creation, legalization, financing, suspension and dissolution of parties in the Gabonese Republic. In view of the proliferation of parties in the country, this text appears to be a major political reform. According to the new provisions in force, in order to maintain an existing party, legally recognized or in the process of being legalized, there must be at least five national and 30 local elected representatives. At the end of the legislative and local elections in 2025, parties that have not met these conditions will be ‘suspended’ or ‘dissolved’: a perceivably ‘liberticidal policy’ that patently undermines opposition. Similarly, the conditions for legalization of parties have been tightened: 12,000 members spread over the national territory are required to legalize a party; while to ensure the reality of these memberships, each party is required to provide the personal identification number of its members. Far from achieving consensus, this law rather discourages the proliferation of parties and encourages the formation of political coalitions. Another long-awaited reform is the redistribution of electoral districts. Several opposition figures, including the National Council for Democracy, have suggested the abolition of the Senate, which was considered budget-intensive, and the division of electoral districts on the basis of demographic criteria so that the nationally elected representatives represent more or less the same number of citizens. The objective is to correct the disparities in the representation of local authorities in parliament. Unfortunately, apart from the granting of two seats to the Gabonese diaspora, several provisions in force before the coup d’état remain as they are. These include bicameral parliament and over-representation of Haut Ogooué in the National Assembly (23 seats against 18 for Woleu Ntem). In short, the project of rebuilding the state at the origin of the coup d’état seems to have been relegated to second place under the transition. Because of his ambitions, President Nguema has given more priority to the development of infrastructure to increase his sympathy capital among his fellow citizens in the run-up to the presidential election of 12 April.

Modernizing the state has been one of the main pillars of Nguema’s presidency—an area of great importance to the Gabonese people. President Nguema has accordingly placed the country under comprehensive construction to the great satisfaction of his fellow citizens. Since 2023, significant resources have been mobilized to finance a vast infrastructural development project in the country: including the construction of administrative cities to house state services and reduce rental costs; the building of municipal markets, schools and universities; the redevelopment of urban roads and watersheds; and the continuation and delivery of projects initiated by the former regime. A thaw in civil service recruitment had also ensued, which has been suspended since 2018. This has resulted in large-scale recruitment among civil servants; rehabilitation of student scholarships; regularization of the administrative situations of state employees; staggering public debt; and the development of a new economic model in order to ‘ensure sustainable and shared growth’ and the takeover of certain national companies. Are the Gabonese more sensitive to these initiatives rather than to the problems of restoring institutions and good governance?

shop the republic

REFUNDING THE STATE: NGUEMA’S DIFFICULT BET

Celebrated ‘for having put an end to the perpetual government of the Bongos,’ Nguema began as the central symbol and embodiment of ‘change’ for the Gabonese people. But once in charge, President Nguema seems to have turned away from this ideal.

Good Governance: One Challenge of Nguema’s Presidency

Good governance principles, a prerequisite for achieving Nguema’s development objectives, have certainly been established in Gabon’s new constitution, but challenges persist. Under Nguema’s presidency, certain practices—such as lack of transparency in the management of the state—have simply continued since the former regime. In the aftermath of Gabon’s coup and the arrests of oligarchs of the deposed regime, for example, large sums of money were seized from the homes of those concerned. Certain images shocked public opinion and legitimized the coup d’état. But to date, not all light has been shed on the use of this manna by the new authorities. The same is true of the rewarding of public contracts under Nguema. In a state governed by the rule of law, the awarding of public contracts is done by call for tenders, but President Nguema favours it more by mutual agreement, fuelling suspicions of corruption and mismanagement. Some members of the government and those close to the president have also been involved in embezzlement without being bothered by the courts. Additionally, since 2023, most infrastructural development projects have been financed by the CTRI—or at least, they appear to have been, according to the billboards on construction sites. But the CTRI is not a state institution. So, where do the resources for financing such significant projects come from and what has happened since its dissolution? In an environment where the moralization of public life is promoted, this gap between democratic ideals and realities on the ground constitutes a real challenge for President Nguema, who is very much inspired by Omar Bongo’s policies.

Conniving with the Former Dominant PDG Party

A regime change presupposes a permutation of elites in power and in the opposition—but above all, a ‘radical’ change in the mode of governance. In Gabon, this has not been the case—at least ostensibly. One of the most striking facts since the fall of Ali Bongo is the alignment of the PDG with the positions of President Nguema. Indeed, after having campaigned for YES in the constitutional referendum, this party was, despite harsh criticism, including within its ranks, at the heart of the campaign coordination for the candidate of Nguema. Jean Pierre Oyiba, former chief of staff of Ali Bongo, was appointed Nguema’s campaign director; several figures of the PDG coordinated the campaign of the latter in their respective political fiefdoms. During these consultations, Nguema seemed to be the ‘PDG’s candidate’. These conniving relations, which give rise to sharply divided opinions, make the ideal of rupture to which a significant fringe of Gabonese aspires not very visible. Moreover, the permanence of the former regime’s cadres in the politico-administrative apparatus has resulted in low turnover of political and administrative elites in Gabon.

shop the republic

‘MAKING SOMETHING NEW OUT OF SOMETHING OLD’: THE MEANING OF PRESIDENT NGUEMA'S ‘RUPTURE’

Regime change inevitably indicates a regeneration of the political class and a paradigm shift. While the available data does not allow us to assess the dynamics of the elites in charge, two observations can nevertheless be made. First, the concern for the continuity of the public administration led President Nguema to maintain certain technocrats of the former regime from the beginning of the transition. Secondly, changes have occurred across the ministries, in the military administration, and in President Nguema’s entourage. ‘Turning the page on Bongo’ means excluding a fringe of Gabonese. But President Nguema wishes to ‘make all the country’s living forces contribute to building a new Gabon.’ As if to convince himself, he claims that within the Bongo regime of which he was a member, ‘not all were bad.’ Hence, the policy of ‘inclusion’ that he advocates. For President Nguema, it is possible, in Gabon, to ‘make something new out of something old’; in other words, to build a new Gabon with those who have been carving it for decades. This political vision has killed the hope aroused among the population and contrasts sharply with the rupture announced in the aftermath of the August 2023 coup d’état. The opposition and civil society—almost totally neutralized—denounce the reproduction of a system that President Nguema claimed to have abolished: the republic of ‘cronies, rascals and inbreds’ regenerating in Gabon. Clearly, the sustainability of the Bongo system, characterized by nepotism, clientelism and favouritism in recruitment and appointments in the state apparatus, still has a bright future in Gabon. In light of the work carried out by local researchers, this situation is unsurprising. For many analysts, Nguema’s ambitions for rupture and renewal are hampered by the multi-positioning of the PDG’s executives and their knowledge of the inner workings of the state apparatus and the degree of implementation of the Bongo regime in the country; but also the solidarity among Gabonese elites. It is for this reason that several executives of the fallen regime have been able to reconvert, without transition, into the Nguema regime, which they are working to reshape or even torpedo.

As Gabon marks its 65th anniversary since independence from France—commemorated last week on 17 August—it appears that, unlike the countries of the Confederation of Sahel States, whose leaders reiterate the sovereignty of their states and promote a firm break with former colonial power France; President Nguema advocates continuity, but with an ambition for greater sovereignty over the nation’s strategic resources, which he intends to transform locally. In terms of domestic politics, the fall of Ali Bongo, whose family ruled Gabon for decades, had raised many hopes among the population. But these aspirations and the desire for a radical break with the Bongo regime contrast with President Nguema’s policy, which is resolutely turned towards discreet continuity. Additionally, President Nguema’s origins have enabled him to manage, at least so far, to reconcile Haut Ogooué, a former stronghold of the Bongos, and Woleu Ntem, a reputed stronghold of the opposition. By advocating inclusion and reactivating Omar Bongo’s policy based on a geo-ethnic distribution of power, President Nguema has achieved consensus and has surrounded himself with elites of all political persuasions. This policy goes against the tide of promises kept and hopes raised⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N3 An African Manual for Debugging Empire

₦40,000.00

US$49.99