Illustration by Sheed Sorple Cecil / THE REPUBLIC.

THE MINISTRY OF GENDER X SEXUALITY

Driving Through Life as a Fully Veiled Muslim Woman

Illustration by Sheed Sorple Cecil / THE REPUBLIC.

THE MINISTRY OF GENDER X SEXUALITY

Driving Through Life as a Fully Veiled Muslim Woman

My mother bought me my first car; I was 22. Growing up, I was one of those ajebutter kids who were chauffeured everywhere. I recognize now, well over another 22 years since, that there is a potential conversation lurking here about privilege, and how life’s most tenacious values are instilled in the formative home and family of your childhood. And maybe we will have that conversation. Someday.

At the time, though, all I knew was a lifetime of my parents’ ‘protective’ parenting that curtailed my teenage outings to only what a car and driver could be spared for. Which wasn’t particularly confining for the loner my teenage self was. As long as I had books, I was content to remain curled up within the gilded cage of my parents’ expectations. Which, of course, left me wholly unprepared to navigate the hellscape that was the Nigerian public transport system, a menace I suddenly found myself in, on my own, as a university student in the historic largest city in West Africa. What can be said about the experience of Ibadan buses and kabukabu, except that the gift of a car meant freedom in more ways than I could articulate. All I needed was to learn how to drive.

My mother herself does not drive.

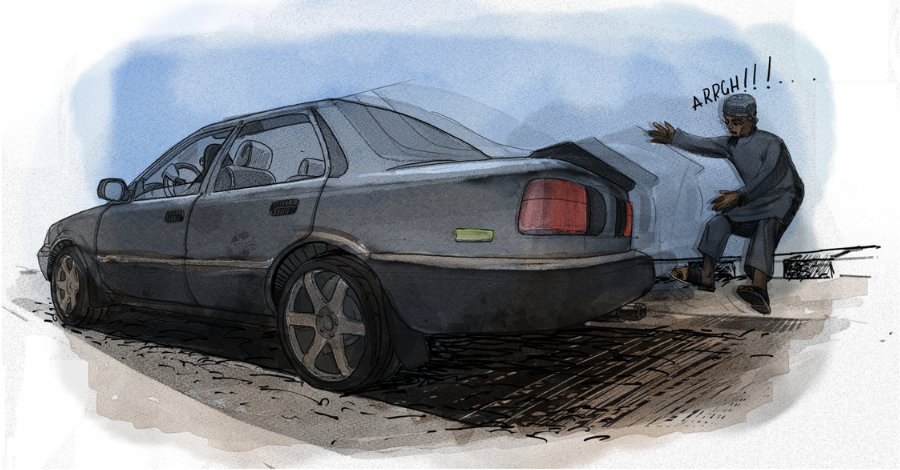

I have vivid childhood memories of watching from the balcony of our flat as my father attempted to teach her. Picture this: the rare peace of 1980s Lagos on a lazy Saturday morning suddenly shattered by sounds of shimmering frustration emitting from the throat of a six-foot, 250-pound man.

‘Oya reverse, reverse! Good. Now, turn left. LEFT, not right! Oloun o! Just stop, STOP!!!’ He would invariably jump at this point. Out of the way, into the driver’s seat to take the wheels, or—on at least one occasion—into the gutter to avoid being rammed by his wife’s ineptitude behind said wheels.

By which time, onlookers from our 100-plus-people Mushin Olosa compound, me included, are roaring in laughter.

‘Alhaji and his wife are at it again.’

‘We don tell him: women no sabi drive.’

‘No mind am, na alakowe dey worry dem.’

But my father would not be deterred. Raised the only son of a widowed kolanut trader in a tiny village on the edge of a mythical river, his dreams were bigger than his origins and he had specific ideas of what was befitting the wife of a man of his status.

So, every Saturday for too many weeks, maybe even months, they were out there—my parents—providing comic relief for the neighbourhood. He eventually gave up, settling for a similarly grandiose version—my mum has had a car and a driver ever since.

My little brother started driving at 13.

No one taught him. He simply watched the drivers closely, and whenever no one was home, he experimented on one of the six cars my father somehow always had at any given time. Soon, he graduated to taking cars out for unsanctioned rides. Then one day, his run was over—inadvertently exposed by an old woman from the neighbourhood who came crying to my mother that my brother had knocked her off the road into the gutter. Amidst the confusion—of ‘who?’, ‘did what?’ ‘how?’—I listened. Over the woman’s theatrical wails for my brother’s adamant side of the story.

‘She wanted me to stop and give her a lift, and when I didn’t, she jumped into the gutter!’

To the questions that arose on whose responsibility the mishap was. My brother’s, for taking out the car when he couldn’t drive—since no one had taught him and he was too young, by law, to lay claim to that skill. The car owner, for not noticing that one of the cars had been taken out sometimes during their absence. The gateman, for—presumably—colluding with the boy towards these experiments.

As the first child and daughter, I got my requisite part of the blame; for not ‘watching him properly’, even though I was mostly away at school by then. Yet, at no point did anyone question the supposition he should drive, someday.

***

Did I mention that my first car was a wedding present?

After months of scuttlebutt about how ‘irresponsible’ I was for getting married ‘so young’, and ‘so soon after her father’s demise’ and—

‘He had such high hopes for her too!’

‘First, she started wearing that thing. Now, this… Where’s she running to?’

‘Her father must be turning in his grave!’

The car was my mother’s subtle middle finger to our detractors. A tangible proof that she had not relinquished her parental responsibility for me, marriage or not. She continued to pay my school fees and upkeep for the next three years, until I was established in my first proper job.

Like most privileges we are born to, it was one I took for granted.

At the time, I was more concerned with the sudden ownership of a new-to-me car, and with the still-new husband. He also did not know how to drive, however, so I did the most logical thing. I registered at a driving school.

Imagine it if you will, a sombre Muslim girl—I was three years deep into the unprocessed grief of my father’s gruesome death by then—in equally sombre coloured, voluminous attires that covered her entire body except the face and hands, and a vocally born-again Christian Nigerian man who insisted on addressing her by her ‘married name’. Both of us voluntarily trapped in an ancient Volkswagen Beetle with a (I’m sure!) purposely altered-to-mess-with-students gearbox, while I attempted to climb—I mean, drive—up the hills that pass for roads in Ibadan. Several times a week, for the far-too-many weeks it took me to master the basics of driving, so often that I can still hear him screeching at me: ‘Brake! Brake! Oya, clutch! Clutch! Mrs XYZ!’ I tried to explain that my reaction times were better when I realized I was the one being addressed—but I was just a girl, I suppose.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00

MY ‘FIRST LADY’

My actual first car was a bright red ‘First Lady’.

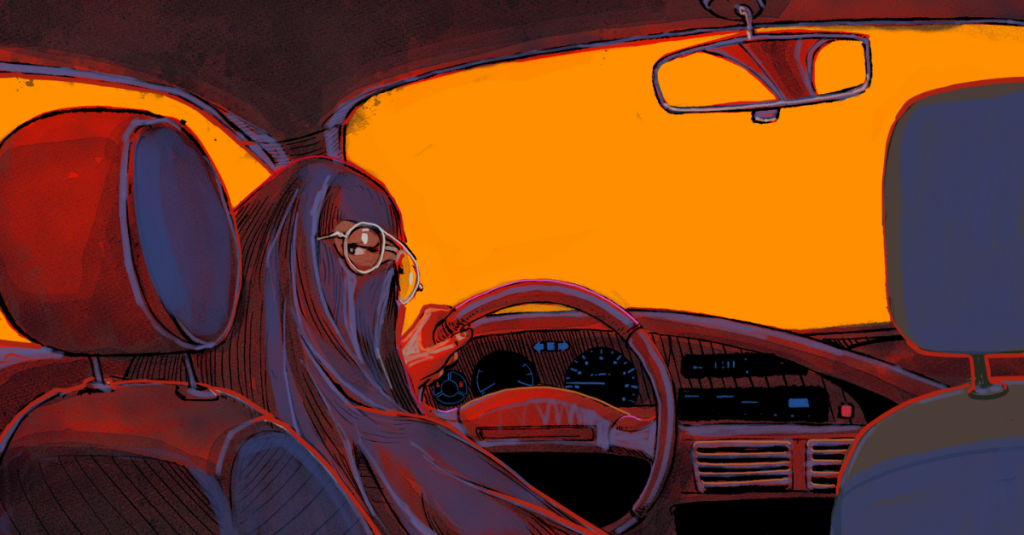

Apparently, the other one had been a starter, and no one really expected me to deal with the erratic mood swings of a German-manufactured vehicle. Thankfully. The smaller, lighter Toyota Corolla and I quickly became fast friends. She was most responsive to the slightest tap of my feet and the tiniest turn of my wrists, and together we flew beautifully through the streets of the cities of my early adulthood—finishing medical school in Ibadan, internship in Bauchi and beginning my career in Abeokuta. Between us—me in what would become my signature black, a fully veiled ensemble with even my face and hands covered, and her in fast-and-furious red—we garnered attention. And Nigerians have never been subtle.

‘Taní gbé mọ́tò sẹ́lẹ́hàá nídìí?’

‘Ẹlẹ́hàá náà ń wa mọ́tò ni?’

‘Can she even see? Better remove that tin from ya face if you wan drive!’

And though I found myself pointing it out on more occasions than I am prepared to admit, the incredulity of ridiculing someone simply for driving in niqab while sitting on an okada or cruising by on leg-edes benz was an irony too subtle for them to catch.

The first rumblings about my driving targeted my husband. In the guise of concern for the Deen, he was badgered: ‘The entire purpose of the hijab is to avoid attention; a niqabi driving is too conspicuous and will attract attention.’

It was the first time I encountered people willing to question my autonomy merely for being female. It opened my eyes to what anyone paying attention would have noticed: too often, ‘concerns’ expressed for women’s ‘wellbeing’ result in restrictions that are somehow meant ‘for their own good’.

Without presuming to speak for others, I wear the hijab to fulfil God’s commandment; I couldn’t care less about any real or imagined attention. Plus, I had spent a lifetime being raised in the borderless expanse of my father’s grandiose dreams and my mother’s unquestioning support. That girl did not grow into a woman who defended personal life decisions to random strangers. She would not reward their sense of entitlement, the supposition that deems it anyone’s place to question a woman’s autonomy by the mere fact of a shared faith, via the proxy of the man they expected to ‘curtail’ her.

The response I offered to my husband, the only man I owed one, was, ‘Aisha gun rakumi.’

TO BAUCHI, WITH LOVE

In Bauchi, my niqab marked me out before my car arrived.

Back then, only a minuscule number of women veiled their faces in the Muslim-majority northern Nigerian city. A Yoruba niqabi doctor, even without her racy red car, was hard to miss. I grew accustomed to the greetings of ‘Yaya, Likita’ wherever I appeared along the oft-travelled axis of my home-market-hospital route, even from people I had no recollection of meeting.

For the most part, Bauchi tolerated us: me, my niqab, my job and my driving. These things marked me out as a stranger in the 2006/2007 Muazu vs Yuguda Bauchi, where driving was still socially a masculine endeavour—except for foreign, non-Muslim and highly educated women.

We were not ‘normal’ women.

Despite the occasional conversations with my northern Muslim women neighbours, who couldn’t understand why I would ‘suffer so much, just to work and drive’ when I had a husband who ‘should be responsible for me’, I was grateful for the respite that came with having no expectation to conform. It was an exceptionalism that would serve me well in the future.

NEXT, ABEOKUTA

In Abeokuta, I had my pick of cars—and the privilege of people.

There, in the land of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, the first Nigerian woman to drive a car, I finally said goodbye to my trusty ‘First Lady’ after four lovely years together. She was replaced by a black Peugeot 406 with shiny chrome wheels and a less temperamental AC—more befitting of my new station as a doctor. Secure in my government hospital job which, in the late 2000s Nigeria, still meant a relatively comfortable middle-class status, I was yet to buy myself a car. And if the 406 ever stopped, often because I’d forgotten to fuel it; I was that much of a spoiled princess!—I would park it by the roadside and call my brother, now a twenty-something, six-foot-plus doppelgänger of our father. He would send someone to deliver another car and look at my 406, while I went about my day, unconcerned by pesky details like what goes into maintaining cars.

Abeokuta meant people knew me, and for every person who challenged my temerity to drive with my face covered, there were nearly as many who leapt to my defence.

‘Do you know who she is?’

In Nigeria, nothing breeds confidence quite like ‘knowing people’. It is the kind of confidence that unsettles others, making them hesitate when you show up unapologetically—suddenly unsure who the Ẹlẹ́hàá beneath the veil might be, or whom she might know. Because really, ‘how else can she be this audacious?’, as I once overheard a traffic police mutter when he waved me through, after I refused to cower before the particular brand of bullying displayed at roadside checkpoints in Nigeria.

shop the republic

A NEW KINGDOM

In 2010, I moved to the only country in the world with a ban on women driving, Saudi Arabia.

I was aware of the ban, of course—Western press loved writing about it. But by then, I had spent five years practising medicine as a niqabi in my own country and, worn out from having to justify myself—my qualifications, my mode of dress, my audacity to combine the two—to nearly everyone I came across, I was choosing my battles.

While the Western press and feminists of the time focused on human rights violations arising from the ban, two things stood out for me. First was the absurdity of hiring foreign female professionals to work in healthcare, education or in training local female workforce, yet denying them a basic life skill that would have eased their professional lives. After a sixteen-hour shift delivering babies, some of them surgically, I watched twelve-year-old boys, ‘RTAs waiting to happen’, as we called them, careen down the hospital roads, driving their mothers or sisters to work or for medical care. Meanwhile, women healthcare workers like me—with our myriads of degrees and life-saving abilities—loitered about, waiting for our drivers to grace us with their presence.

Secondly, for a country that almost single-handedly exported the ‘modern’ textual and literal revivalist understanding of Islam to the rest of the world, the driving ban—framed in the language of a fatwa—did not proffer single textual evidence from the Qur’an or hadith. As someone who adheres to the same textual and literal revivalist understanding of Islam, the ban and its eventual overturning remain, for me, one of the most glaring displays of why ideology must be distinguished from those who wield and claim to implement it. In any case, while the ban hardly mattered to Bedouin women in remote tribal areas, who neither knew of nor cared about it, for every other woman in the Kingdom, it stayed firmly in place until 2018.

LOVE AT FIRST…

The automobile love of my life was not a car.

One early morning, after another overnight shift that had begun to weigh heavily on the ‘hate’ side of my love-hate relationship with clinical medicine, exhausted but relieved to have survived, I stepped outside to wait for my driver. Then I saw her. And yes, such beauty could only be a ‘her’. I fell. Hard.

‘Woah!’ My exclamation slipped out loudly enough to catch the attention of the men hovering nearby. Even their watchful eyes could not stop me. I moved closer, circling the hunk of metal that had me in its grip, my admiration on full, unashamed display—in the way a woman like me was rarely permitted. I made two slow loops of tawaf around her, taking in her sleek lines. the curve of her body so low to the ground, the shiny purple-blue of her hue, the black accents.

I took a picture, and in that instant, my other life flashed before me. The life my high-school self once imagined. In that life, this beauty was mine. I was a cardiology professor, one with enough gravitas in my corner of the world that she and I could zoom into the hospital together. Late, of course—not for dramatic effect, but because lateness is my constant, even in this life. I was wearing the obligatory sunglasses to block out the sun and to mask the dgaf glint in my eyes from the admiration or censure of onlookers.

I lose the thread of my fantasy when the men crowded me with comments I could no longer ignore. In an instant, I was myself again—an overworked and overwhelmed niqabi in a flowing black abaya that would spell disaster on the back of the power bike I had just fantasized over. Only my sunglasses survived the transition.

WARRIOR WOMEN…

Saudi women fought for the right to drive.

Long and hard, they battled in small pragmatic ways as much as loud defiant ones. Educated Saudi women found their voices in foreign media or behind the wheels on the streets of Jeddah and Riyadh. But the unsung heroines were the women of small-town Saudia, like the cleaner in my old hospital. One night, while alone at home, Badriyyah had driven her aged mother-in-law to the hospital after the old woman suffered the first stages of what turned out to be a haemorrhagic stroke.

‘I did not know how to,’ she confided in me later. ‘But I did not have time to think about that. [Her son] did it at 11 years old, there is no reason I couldn’t!’

These women fought bravely until the ban became too much of an embarrassment for those with power to overturn it. It was a fight I had no bones in—remember the exceptionalism I mentioned earlier? And, as an ‘alien’ in a Police State, it was a fight I was glad to sit out.

shop the republic

***

In September 2017, Saudi Arabia announced the end of the driving ban, scheduled to take effect a year later. The news hit us, Saudi women and women living in the kingdom, with the same shockwaves it sent across the globe. There had been no premonition and beyond its obvious PR value, the decree did not seem feasible. Or so we thought.

We were all wrong.

Immediate preparations began to make the less-than-a-year deadline feasible. Almost overnight, protocols emerged to licence women drivers, starting with those who already held valid licences from other countries. Driving schools sprung up like mushrooms, spurring the training and recruitment of female driving instructors and traffic officers.

Next, sanctions were announced. The first publicized punishments against those who opposed the idea of women driving—such as burning the first car bought by a woman in Ta’if—were swift and almost brutal. Driving demerits, hefty fines and even jail time ensured that those who had sworn it would never happen quietly learnt to accept women as equally deserving of the right of way. And contrary to condescending jokes that filled the year between the announcement and its execution, women driving did not increase the rates of accidents. Rather, by 2021, Saudi Arabia recorded almost a 35 per cent reduction in car crashes.

THE END OF THE BEGINNING

I made the monumental decision of my middle-aged life while driving.

A few minutes past midnight in January 2020, I was behind the wheel of the first car I had ever bought for myself. Like the rest of humanity, I was unaware that a global pandemic was about to reshape my world. Tentative, after nearly a decade off the road, I inched across the four-lane highway linking Sabya to Jazan, heading home after a long shift. Behind me, a colleague who had kindly offered to serve as my escort followed patiently in his own car. With his lights dimmed, he waved off the impatient Saudi drivers riding our bumpers. His presence gave me the sense of security I needed to reclaim a skill I had once loved but had lost confidence in during the decade of living in a country that forbade it.

That singular act of kindness—from someone who owed me nothing and expected nothing in return—threw a sharp glare on my life, on all I had denied, explained away and excused for over 18 years.

If they wanted to, they would! Isn’t that how the popular logic goes? That night, I finally understood.

When I got home, I wrote an affirmation and stuck it to my mirror. ‘Today is the first day of the rest of my life!’

Then I systematically went about dismantling the life I had spent nearly two decades building. It took almost two years, but in 2022—amidst a host of other life changes—I quit my job and left Saudi Arabia.

I have never once felt the urge to look back.

***

Did I mention that I bought that car the same year I removed my uterus?

While I am unsure of the correlation, the latter ushered in a new era of my womanhood. It would evolve over several years, but I had entered my ‘Done!’ era. With four decades behind me and a life of juggling so much that, looking back, I can only marvel—How did I do all that? Why did I do all that?

The car should have been a clue. A next-year model jeep in an uncompromising grey, ‘masculine’ as the car sales guy called it after failing to sell me a lavender contraption that looked like it belonged in a pop music video. It had everything I needed: stamina for my between-city commutes, leg room for the son who wouldn’t stop growing and more than enough space for his bickering sisters—without the bells and whistles of excesses.

That car became another way for me to make memories, to live in the moment—something I had only just started to learn. I took long, destinationless drives with my kids, blasting old-school nasheed sing-alongs or Qur’an recite-offs, as the mood caught us. I had my first year of school runs behind the wheel, mostly with my youngest. Those drives gave us a rare alone time to bond, away from her much older and often domineering siblings. Together, she and I traversed Jazan traffic while listening to audiobooks of all Tsitsi Dangarembga’s novels in order of publication.

Then there were the inevitable fuelling and car wash trips with the son. Apparently, being cocooned inside a wall of bubbles was a favourite place for sharing vulnerabilities with a meddling mother. There were cafe crawls with my older daughter, living out our Saudi girl dreams and hours of long, solitary drives I took in an attempt to hold on to sanity amidst the chaos of my own making. When we left Saudi Arabia, that car was one of the few losses I mourn.

DRIVING BACK HOME

I taught my son to drive in that car—or at least, I started to.

We practiced on the empty stretches of roads in Jazan and Hafr al-Batin, our last two cities of residence in the Kingdom. Later, we would take another car down the narrower roads of the Abeokuta estates of my mother’s house, where we relocated to. She had spared me both an apartment and a car while I figured out what came next.

I consider both an extension of the parenting I’ve always known—my mother’s steady support and my own role in teaching my son a life skill. She has done that all my life, quietly being there whenever I needed her, just as I have done him. Nurturing his cautious and sensitive nature while gently but firmly nudging him out of his comfort zone.

At almost 17, this was all he knew too; it never occurred to him to question the gender of his driving instructor. He slowly gains confidence and momentum with the passage of time. Soon he is braving the potholes of the general Abeokuta roads and the menace of their users. By then, we—the gangly 6-ft-6 boy and his Ẹlẹ́hàá mum—have become accustomed to the stares.

***

My daughter does not drive. Yet.

She is a sum total of the women who came before her, and of the places that raised her. Like my mother and the average Saudi woman comfortable in the softness of their lives, she is more than happy to let others chauffeur her. Almost 18, she has expressed no interest in driving. But like me, and the Nigerian Yoruba woman in her blood, I know she will raise a furore if anyone ever attempts to prevent her from doing so.

She understands too well how quickly privilege can slip into restriction, and she carries the awareness of the generations of women whose sacrifices have given her the freedom to choose. That knowledge allows her to exist as a teenage niqabi on the verge of university, with the autonomy to decide what she wants for herself. Amid the recent uncertainties of our lives, admittedly of my own doing, we are both content to leave it be at that. For now.

DRIVING IN THE HEART OF THE EMPIRE

Technically, a new immigrant to the UK can legally drive.

But as an international student on a shoestring budget—overqualified (yes, I applied and was turned away!) for the borderline exploitative minimum-wage jobs that sustains the country’s existence- driving was a luxury I had neither the time nor the inclination to explore. But after a year immersed in all things literary, my program ended, and I knew two things for sure: my writing was not too shabby and I had no interest in being a poor artist. So, I took a doctor’s job.

Now, weeks into my new role, I am finishing this essay on a work trip with the only other POC on my women-only team, K. We bond, two middle-aged immigrant women, by trading stories about learning the rules of British driving. She commiserates with the shege my Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) applications put me through—I couldn’t apply online because the system couldn’t verify one of my old addresses, my first signature form was lost in the mail—as we traverse the roads of south England with exaggerated care.

K is prone to road rage, I think, judging by the slow exhale she lets out whenever someone with a bloated sense of their own driving skills cuts her off. I tell her this and she laughs wryly.

‘Back home, maybe,’ she admits. ‘Here, though, one has to be careful. I don’t know anyone here.’

I reflect on that—thinking about the relativity of privilege and how life unfolds in endless loops of similar cycles. Once again, I am navigating driving lessons, new roads and the mannerisms of their users, getting a new license and the purchase of yet another car.

K asks what I’m writing, and I tell her.

She shoots me an incredulous look. ‘Why would anyone question that you, an apparently sane adult, should drive?’⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N3 An African Manual for Debugging Empire

₦40,000.00

US$49.99