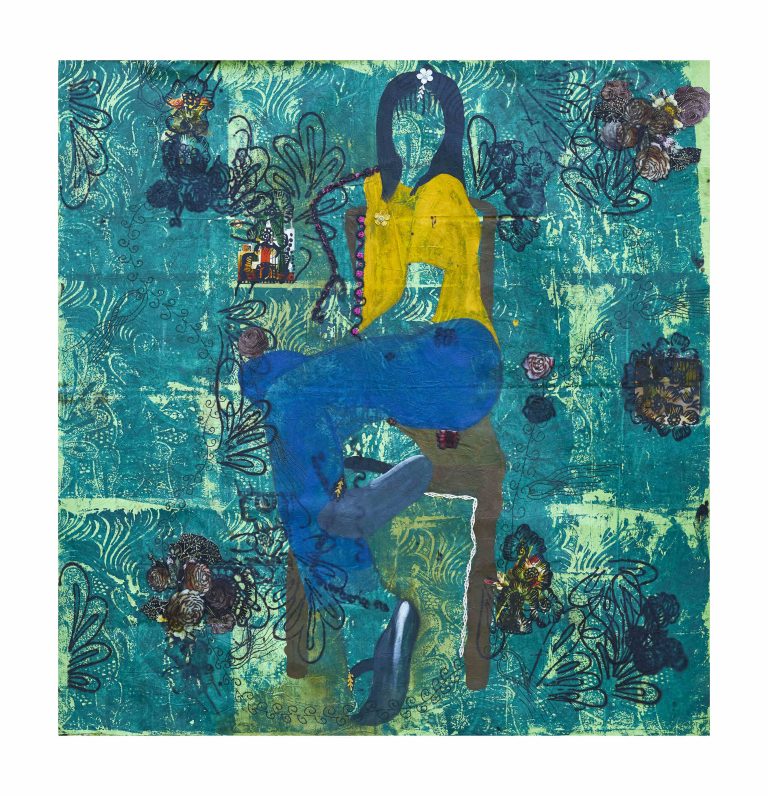

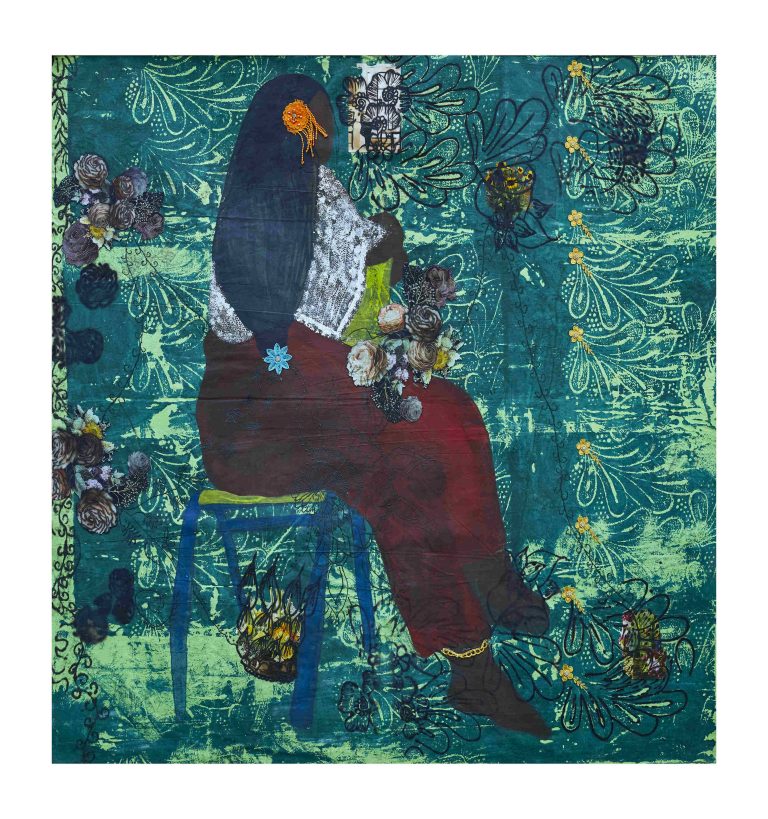

The Linguist, 2023. Art courtesy of the Artist / HALIMATU IDDRISU.

THE MINISTRY OF GENDER X SEXUALITY

The Body, the Veil and the Muslim Woman

The Linguist, 2023. Art courtesy of the Artist / HALIMATU IDDRISU.

THE MINISTRY OF GENDER X SEXUALITY

The Body, the Veil and the Muslim Woman

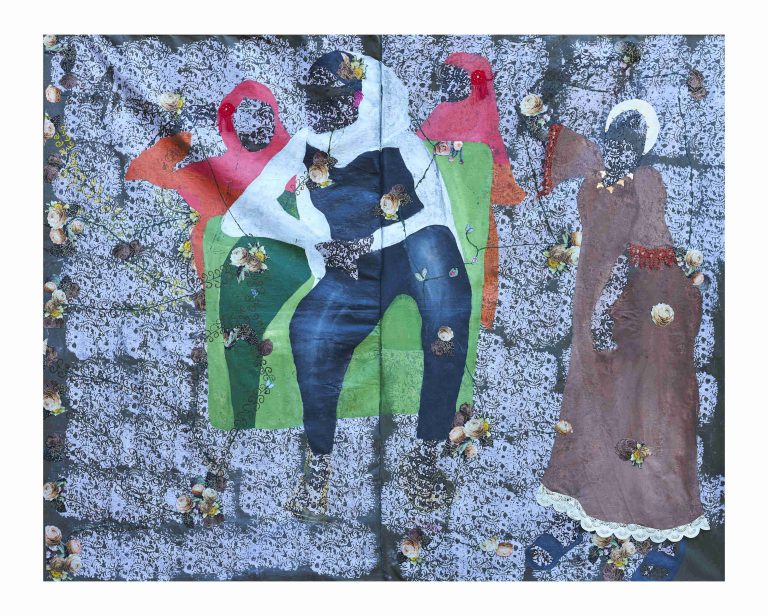

Faceless forms of women moulded by the outlines of their garments. Halimatu Iddrisu, the artist who paints them to life, strips you of the power of individual referencing. The parts of their bodies that are depicted to be unclad are transparent. Iddrisu is insistent on concealing what the absence of clothes can say about the skin. Like their bodies, their heads are shaped by what covers or adorns them: turbans, headscarves, hijabs, natural hair, weaves or braids.

Some of Iddrisu’s paintings bear solitary figures. Like the woman wearing a hijab and outfits in different shades of blue who sits folding her legs inwards—this is the face of Shrouded Mysteries, the exhibited collection at Nubuke Foundation that marks my first encounter with Iddrisu’s art. In others, women stand (or sit) together as sisters of one faith, with and without head coverings. These elements come together to convey the one thing Iddrisu wants you to know and how she wants you to identify her subjects: Muslim women navigating the complexities of faith.

Iddrisu’s work holds her autobiography as a Muslim woman in Ghana. It encompasses her encounters with other Muslim women in the communities she has lived in and the various ways they choose to dress. It is especially the manifestation of how she navigates the conservative restrictions Islam places on her artistic techniques to show the various facets of appearances that Muslim women embrace.

THE ART OF REBELLING AND ADHERING

Transparent figures of nude women painted on hijabs were Iddrisu’s earliest professional artworks, created in 2019—three years into her BFA (in Painting) programme at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi, Ghana. Beyond the challenge of finding models, this artistic path dismayed her father so deeply that she had to work outside of home. In line with Islam’s principles of modesty, the nude imagery in Iddrisu’s art is widely disapproved of, especially when they appear on a garment deemed sacred. The use of full figures also defies the prohibition against figurative art, a major constraint guiding the making of art in Islam. While interpretations of the Qur’an’s stance on this vary, the prevailing view—drawn from the Hadiths, records of Prophet Muhammad’s sayings and deeds (sunna)—warns against imitating Allah’s creation. As narrated by the Prophet Muhammad’s companion, Abdullah Ibn Umar, the Prophet cautioned: ‘Those who make images will be punished on the Day of Resurrection, and it will be said to them: Bring to life that which you have created’ (Sahih al-Bukhari). This grounds aniconism in Islamic art, steering it away from human and animal depictions toward intricate calligraphy, geometric designs and floral motifs.

The resistance of her style prompts Iddrisu to begin probing what she terms ‘the ideology of the non-figurative in Islamic art’, questioning whether facial features alone define an animate figure and what other elements might do so in Islam. Her findings and personal reflections give rise to a new method of portraying Muslim women: rendering their figures incomplete, so they do not fall under the category of prohibited images.

The appraisal of Iddrisu’s work is incomplete without the consideration of extrinsic elements. This soon becomes clear as she details the relationship between her and her subjects. Iddrisu shares an affinity with wilful women, rebellious maybe; she was one herself. Her question, ‘why?’, when she saw women in Israel Lomnava (an area where she grew up in Accra) remove their veils once outside their homes, found an answer when she herself took to wearing ‘tight trousers, miniskirts and hair extensions’ while she was in the university. She was free from her parents’ insistence on dressing as dictated by Islam.

Born in Nima, a predominantly Muslim Zongo community in Accra, Iddrisu grew up in a household where her father, though not strictly conservative, was firm about how a Muslim woman should dress—head coverings were mandatory, and trousers were for men only. She also experienced the duality of living in secular spaces as a Muslim woman. Iddrisu attended schools run by Methodist churches and so hijabs were not allowed. Yet on weekends at her Islamic school, she had to wear one. University offered her the freedom to spin her dressing choices, eventually leading her to embrace turbans and hijabs as a personal expression of faith. ‘It took me three years of exploring my own body to understand what it meant to resist the hijab,’ Iddrisu told me.

The Qur’an’s standard on modest dressing for women centres on the concealment of their awrah—the parts of the body excluding the face, hands and/or feet—from non-mahrams (those of the opposite sex who are not close relatives and are therefore marriageable). Iddrisu’s art stands as an omniscient observer, passing commentary on the varying degrees to which the women around her collectively adhere to this rule while fashioning their individuality. Her work is informed by the life she has lived. Reaching into her past, Iddrisu tells me:

Where I was born, you’d see many women resisting the hijab despite being denounced and urged by Imams during every Jumat Khutba. It is the same in Israel Lomnava, the community I was brought up in, where elderly men constantly encourage women to wear the hijab or burka.

This reality of women removing their hijabs also features in the present she sees—women continuing to hold onto their faiths, defying labels of being a disbeliever. ‘I started going to some Zongo communities in Kumasi and then I would have long conversations with the women about why they don’t wear the hijab (as prescribed). I also do the same anytime I visit Accra,’ Iddrisu reveals. These women often shared with her the never-ending backlash they face for how they dressed—whether they wore the hijab or not. They opened up about how their reasons were completely disregarded, especially by men and religious leaders who simply undermined them as a way of caution. Over time, these women became Iddrisu’s friends and later, her muses. This becomes the cycle of Iddrisu’s process: if she has painted a woman, she must have listened to her first.

One thing remains constant in Iddrisu’s career: her dedication to centring Muslim women and exploring their choices in appearance—a freedom often criticized within Islamic communities. From the nude forms in her earliest works to the veiled and unveiled figures in Shrouded Mysteries, and the women in Nisa’al Qadr who daringly combine ‘virtue’ with ‘vice’, Iddrisu charts a broad spectrum of expression, from strict adherence to complete rejection of the hijab.

shop the republic

MEDIUMS AS MEANING MAKERS

For Iddrisu, the question of how to paint human figures within Islamic constraints leads her from the nude and becomes a guiding force in her work. As she transitions from one style to another, without fully conforming to Islamic tradition or completely embracing figurative art, Iddrisu employs her mediums to explore freedom and the relationship between women and Islamic culture. One such medium is her preference for unframed fabrics as the canvas for her art. She views framing as a kind of restriction that contradicts her person. ‘Once there is a four-sided frame or the work is confined to a canvas, it feels caged and restricted. The work should move freely with the wind—it is not meant to be static, just as I see myself as someone who isn’t bound to one place or thing,’ she explains.

Assembling materials to grant them symbolisms and make meaning is a language that Iddrisu speaks with mighty mastery. Wet and dry materials—paint, henna, oil pastels, hibiscus, fabrics, beads, hair extensions—all gather to reveal the influence of Islamic customs in the cultural expressions of (Ghanaian) Muslim women. Iddrisu’s use of henna as a liquid medium alongside paint particularly interests me. The dye is widely known as the ink Muslim women use to temporarily tattoo decorative patterns on their skin. Iddrisu adopts it to offer an authentic portrayal of the Muslim women in the communities she has lived in, how they selectively integrate aspects of Islamic practices into their lives and their peculiar ways of doing so. According to Iddrisu:

The traditional henna is cultivated in northern Ghana. It is often used interchangeably with imported dyes from China which contain PPD, a chemical that causes skin allergies. Despite its health risks, women in Zongo communities choose the imported dye for its darker tint and brightening effect. Even those who use traditional henna still mix it with the imported version. Similarly, in my work, I use both, but mostly the imported dye. Another thing that fascinates me is the layering process. The traditional dye, which ranges from pale orange to deep burgundy, is applied first, followed by the imported black dye on top. I love how they experiment with layers on their skin, and I’ve borrowed this concept in my art. That is why you would see lots of layering in my work. It is something I have taken from this community.

In her work, these mediums complement her method of representation, helping to embody the themes intended. Each material carries its significance in the context in which it appears. The layered, geometric and decorative patterning of henna that often form the backdrop for her figures and spill over onto their bodies as tattoos. Hair extensions that show the absence of the hijab (full or partial) and the presence of a prevailing beauty trend. Fabrics that are well-known for making hijabs, permitted to be worn by women, and others that reflect how Muslim women negotiate the choice to wear—or resist wearing—the hijab.

shop the republic

WOMEN INSIDE AND OUTSIDE

There are varying interpretations regarding veiling and dressing standards for women in Islam, thus influencing the designs of veils and its enforcement. Iddrisu’s work is concerned with the tension between ‘what should be’ and ‘what is’, contextualizing its practicality within real-life circumstances. She often sees heat deterring women around her. ‘Temperatures in Ghana range between 27 to 34 degrees year-round. Because of the heat, the women prefer adapting their turbans or choosing to not wear the hijab at all,’ Iddrisu tells me. This also comes into play with work. ‘Women in Zongo communities do a lot of work, often selling goods on the street to support their husbands and families. You wouldn’t expect them to wear a full hijab or burqa while working outside in such hot weather,’ she continues.

Some younger women rhetorically ask Iddrisu how she expects them to attract potential husbands if they fully cover their bodies (and faces) with hijab. ‘Someone once told me simply that the world was evolving and one has to adapt to fashion trends,’ she recalls.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

shop the republic

The discourse around hijab and modesty among Muslim women has long enjoyed (or more accurately, suffered) magnified focus. However, the observance of hijab is not often approached as an act of worship that exemplifies submission to Allah. It is, instead, frequently portrayed as a tool designed to shield men from ‘temptation’ or render women invisible and voiceless. Thus, the discussion of modesty continues to centre disproportionately on women, neglecting Qur’anic injunctions for men to lower their gazes and guard their private parts. This also means that their transgressions and consequences are rarely spoken of with the fervour reserved for women’s dressing.

The male dominance in the interpretation of Islamic texts leaves women vulnerable to patriarchal distortions of Islamic principles. Critiquing this dynamic in her analysis of a Hadith where three women speak to Prophet Muhammad unveiled, only to cover themselves when Umar enters, Khairunessa Dossani, in ‘Virtue and Veiling: Perspectives from Ancient to Abbasid Times’, argues that the male authority in Islam became ‘harsher and sterner toward women than the Prophet ever intended during his lifetime’. This harshness, she suggests, has escalated into outright violence, with women being harmed or killed by male relatives or authorities over the hijab. The harshness the women of Zongo speak of—the scathing condemnation that ignores the nuance of individual circumstances—spreads through the community, even among women, incessantly tugging at how others dress, policing their actions, and appearing under women’s social media posts. This harshness demands that women remove their hijabs if they won’t wear them ‘properly’ or leave Islam entirely if they choose not to wear the hijab at all.

These complexities of modesty, how it relates to the hijab and social expectations for Muslim women universally echo in Iddrisu’s work. Although she captures it through the lens of her community, her approach to anonymity bridges the individual stories with shared experiences. ‘Even though I use specific individuals to represent what I am discussing, it is not just about them,’ Iddrisu explains. This, she says, is why she leaves the face devoid of any features. ‘That way, during an exhibition, the viewer won’t associate the work with one person but instead connect it to all the women who share similar realities. Some viewers tell me they feel I’ve painted them, whereas I’ve never seen them. That’s the motive of the painting.’

It was this intentional vacancy that drew me to Iddrisu’s work. Being a Muslim woman myself, I stumble many times as I move ahead in my faith. In those moments, I reject definitions that measure my belief by its ‘inadequacies’. I saw myself in Iddrisu’s principal subjects, my face seamlessly fitting into the blank spaces theirs would have been. This connection extends beyond me, reaching countless other women whose stories are intertwined with the struggles and choices depicted in her art.

The exploration of self and others guide Iddrisu’s journey. In the issues she tackles, her methods, materials and the binary of framing or its absence continue to take on evolving meanings, expanding the possibilities of how Muslim women can choose to appear and yet be understood⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N2 Who Dey Fear Donald Trump? / Africa In The Era Of Multipolarity

₦40,000.00