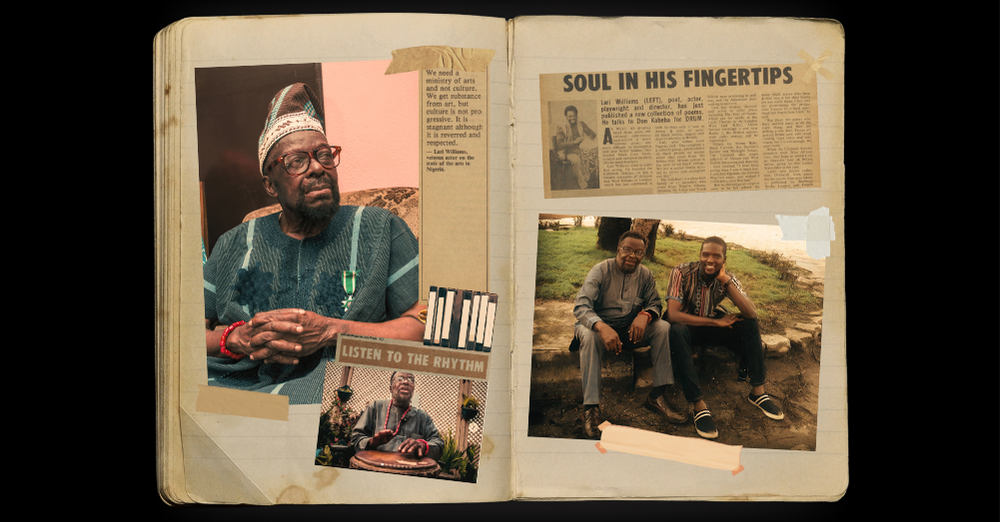

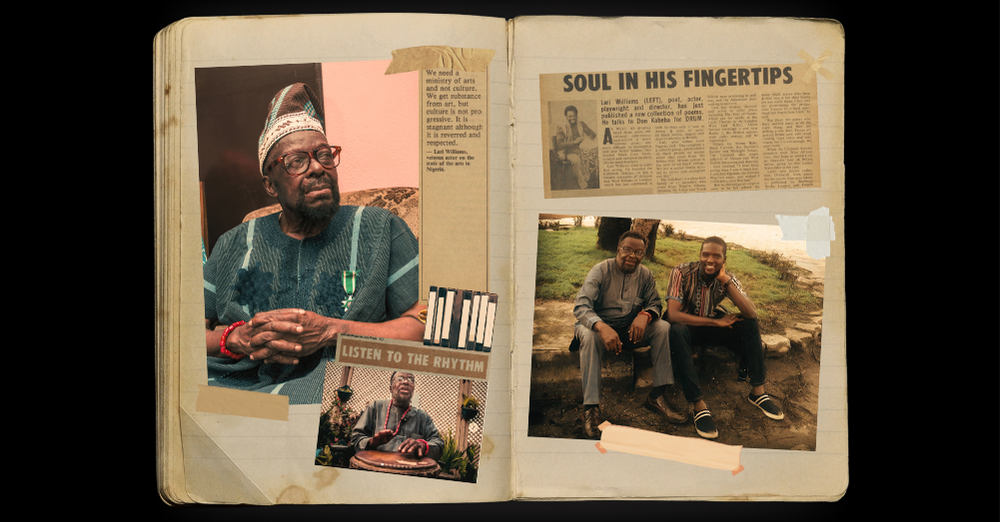

Photo illustration by Dami Mojid / THE REPUBLIC. Ref: Images provided by the Author. News Stories / ARCHIVING.

THE MINISTRY OF ARTS / PEOPLE DEPT.

Remembering Uncle Lari Through Three Characters

Photo illustration by Dami Mojid / THE REPUBLIC. Ref: Images provided by the Author. News Stories / ARCHIVING.

THE MINISTRY OF ARTS / PEOPLE DEPT.

Remembering Uncle Lari Through Three Characters

Three Februaries ago, the curtain fell on my father’s final act.

Notice my attempt at alliterating? Uncle Lari, which is how I called him, would have been tickled by it. He was a very unusual person. Even in moments when it should be the last thing on anyone’s mind, he’d be noticing one literary device or another. No matter what you needed to tell him, if you wrapped it in a clever double entendre, or display some verbal flair, you’d earn bonus points.

On 27 February 2022, Lari Williams MFR—actor, poet, wearer of hats both literal and metaphorical—left a stage he’d commanded for decades. To say he was ‘a character’ feels insufficient. Born in 1940, Uncle Lari was many characters, some of which he played on stage and on screen.

Just like him, my grief has also taken on different characters, wearing different hats, sometimes even taking centre stage. I remember him in unusual ways. Last year, grief channelled itself in a way I think he’d have wanted: whiskey in one hand, slice of cake in the other, John Coltrane and Duke Ellington sneaking into my ears from God knows where and putting me in a sentimental mood.

The year before that, through music, listening to some of his favourites—from juju to classical music and jazz—and even making some myself with my flute. It was one of the interests we shared—an eclectic range of music.

This year, I’m replaying a few films he was in, remembering him through some of the conflicted and chaotic characters he played or that played him. And remembering his love for art and culture.

shop the republic

THE JUJU MAN

I started with a film described as so deliriously awful it looped back to genius: The Witchdoctor of the Living Dead (1985). You know the type: VHS haze, dialogue dubbed by what sounds like a kazoo choir, gunshots that crackled like popcorn. One critic called it ‘the Citizen Kane of crap.’ Uncle Lari called it a cultural heritage saved (the benefit being lifelong bragging rights). Watching it as a child, it scared the Living in Bondage out of me. Watching it now, I still find it scary, but I laugh until my ribs hurt.

If you’re brave enough, you must check it out on YouTube.

Not long after, Nollywood found the native doctor trope and ran with it, Uncle Lari holding the torch. At first, he leaned in—rattling goat bones, scowling into cauldrons, delivering prophecies in a voice that could curdle milk. From Black Powder to Full Moon to Blood Money…

I didn’t like it. My friends complained.

‘Every role’s a new skin,’ he’d say…until he started complaining that the skins were starting to feel identical.

‘I’m a character actor,’ he’d grumble, ‘not a walking juju advertisement! Don’t put me in a box.’

Still, he infused each witch doctor with Shakespearean gravitas. Even when the script demanded he summon zombies to a budget synth beat.

His juju priest roles stirred controversy behind the scenes because Nigerians, being Nigerians, complained about their spiritual impact on him. To make matters worse, our Lagos home was a museum of defiance. After FESTAC ’77—Nigeria’s grand celebration of African art—which Uncle Lari had come home for, he filled the house with Benin sculptures and all sorts: faces frozen in regal disdain, hands clasping sceptres of forgotten kingdoms. To him, they were art. Just art. Well, not ‘just’, but you get what I mean. He saw them as history. Diaries of sorts. Frozen stories.

To certain guests? ‘Idols,’ they’d hiss, edging away like the bronzes might leap off the shelves and hex their Mercedes or their destinies.

‘Brother Lari,’ one aunty warned, ‘these things in your house are demonic. They are the reason why things are not going well for you o!’ Or if anyone around happened to be ill: these things are why so and so is sick.

Uncle Lari would grin and deadpan: ‘Ah, but the demons give the best acting notes.’

‘Superstition,’ he once told me, ‘is just great storytelling,’ handing me the book Demon-Haunted World.

If audiences wanted to confuse his roles with his soul, let them. He knew the difference between art and a cheap script or a cheap sermon. Yet, when the scripts weren’t coming in as often as they used to, he became ‘stitious’. He knew the names of the particular witches who wanted his downfall. Mostly ex-girlfriends.

As someone who liked irony, he’d find it super ironic that despite the disdain with which Nigerians treat these works at home, abroad we’re demanding for the return of the Benin bronzes. We pretend as if Bishop Chinasa Nwosu of the Royal Church in the east and his comrades don’t regularly set ablaze ancient sacred objects, branding them as idols and accursed things. We pretend as if destroying our cultural heritage isn’t a whole industry in Nigeria. We pretend as if what makes the news is when a priest saves these ancient objects, not when they burn them.

Even our intangible heritage like the Isese festival is under attack because two religions are more equal than others in Nigeria. If I were Eyo festival, I’ll be getting ready for my own slap in the face.

shop the republic

THE CLEANER

Away from the juju movies, another film that came to mind was The Sojourn, shot in the early 2000s. It wasn’t one of the popular ones. In it, he played a man who ‘luck’ found after spending many years in prison. He was released and then found work as a cleaner. It was a role about second chances, about starting over when the world has already written you off.

I put ‘luck’ in inverted commas because Uncle Lari said to me that ‘If he were truly lucky, he wouldn’t have been imprisoned at all.’

He loved to reference George Orwell. He told me a story about Orwell’s throat catching a bullet, but it missed his spinal cord by a fraction of an inch.

‘Orwell said, “I was lucky, they said. But if I were lucky, I wouldn’t have been shot in the first place.”’ Uncle Lari quoted Orwell.

He was the most pessimistic fellow I knew. Sometimes, he saw what we’d call luck not as a blessing but as the absence of greater misfortune. Perhaps this worldview was shaped by years of navigating an industry that often felt like a prison itself—one where talent wasn’t always enough, where survival required more than just skill.

Anyway, in preparing for the role, I watched him clean the house like never before. Whistling and placing things in their place, carefully. I found it funny how he’d get into character way before he saw a camera. He’d talk to me in the character’s voice, respond to things in the way the character would. It was weird. He’d criticize actors who didn’t use this method: they play characters, but they lack character, he’d say.

Allow me to digress. Life imitates art. After he passed, in a moment, I became that character—the cleaner; sorting his things in his Ikom apartment in a fog of grief, drowning in old papers he refused to throw away. I really don’t want to talk about how it felt to be in that apartment. It makes the hair on my body stand, as it did when I was there. I sat in a room full of his belongings—old scripts and books, faded photographs, a hat he wore often…stuff.

Isn’t it funny that when a character dies, the actor remains? Yet when an actor dies, his characters remain.

His funeral was like a Nollywood movie of sorts. No, it wasn’t attended by the president or by personalities. But there were costumes, actors, drummers, dancers and then sentiments. Uncle Lari would have hated the sentimentality. He didn’t like funerals (I think his play The Year of the Goats touches on this issue). But drummers he liked.

I wrote a poem before the funeral that I thought might capture how he’d see his funeral. Art imitating afterlife?

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

The Funeral

For Christ’s sake not black clothes!

I could swear I made that clear.

Where’s the array of beautiful attires?

Who is the costume manager?

Didn’t I say Sunday bests?

Did I ask anyone to dismantle the sun

and pack up the moon?

And what are those?

Are those tears?

My God–tears? My people!

For what purpose?

I knew there’d be actors here

but I didn’t think

that included you.

Please wipe those things

with the burial flag.

Acting like you didn’t say:

Good riddance.

No one should be allowed to pay

last respects if they never paid the first

Flowers?!

What are you guys thinking?

Now Mother Earth will have to

attend yet another funeral!

Is that me?

For heaven’s sake,

where is my beard?!

I must be at the wrong funeral,

you bastards.

How dare you?

Who’s over there doing a poem?

It sounds terrible.

Oh, she’s my granddaughter?

Well, can she put life

into it?

I’m the one who is supposed

to be dead, isn’t it?

I’d have preferred all this at night

under the wide and starry sky

so the stars can welcome home

one of theirs.

The drummers are here.

That’s great.

Keep playing

Talking about the night,

why does the night fall

yet it’s the day that breaks?

Can the day be put down

more gently?

I need a pen

Where was I? Oh yes, I was digressing from my digression. Not my fault, I was raised by a master at digressing. He’d be quoting lines from The Trials of Brother Jero between sips of palm wine, then drop a flawless ‘Tudo bem?’ on a Brazilian DJ mid-set, just to watch their face light up. ‘You see this Ankara print?’ he’d ask, pointing to his shirt. ‘Same pattern as Ukrainian vyshyvanka—brothers in thread!’ Uncle Lari made me want to see the world!

Even his proverbs were hybrid, anything to escape dropping a cliché: ‘How water take enter coconut? That is the question.’ By nightfall, strangers swore they’d known him for years. The world, to him, was a jollof rice of dialects, and he made sure every grain stuck to the pot. As actress, Taiwo Ajayi-Lycett put it: ‘He was an indelible part of my notoriously exciting, colourful, eventful and memorable past.’ And mine too, aunty! And now the world feels less wonderful without him.

Uncle Lari was the most optimistic fellow I knew. No, I’m not contradicting myself, he was a contradiction. He had a strange kind of hope. The hope of someone who believed things would get better. That poetry and music would change the world. ‘The world just needs more Wislawa, more Fela.’

His character in The Sojourn was like that. A man who’d been broken by the system but still found a way to keep going. A man who swept floors not because he believed in redemption but because it was something to do. A man who, in Uncle Lari’s body, became resilience.

Uncle Lari hoped and believed that things could get better for him financially. He wasn’t ashamed of his situation. But for me, being broke and famous was the worst thing that could happen to anyone in this world! I was often embarrassed by some of the situations we were in. Hopping on okadas or standing at bus stops with his face slightly turned, hoping some passing driver might recognize him so we could save on transport. I hated it. It made my skin crawl. I wished we were poor, just poor, like everybody else. No questions with it, like why do you live in this area? Why’s your son going to that school? What happened to you?

As I sift through the remnants of his life, I try to find the resilience he had in myself. Not in grand gestures but in the small, stubborn act of just moving forward no matter what. Of putting one foot in front of the other. Of sweeping the dust, even when it feels like it will never stop settling.

shop the republic

SIZWE BANZI

On to another character he played: Sizwe in Sizwe Banzi is Dead (actually, he frequently performed this play on stage entirely solo). For him, this wasn’t just a play; it was a call to action. Through his performances of this play at the National Theatre and beyond, Uncle Lari challenged audiences, to make them uncomfortable, to force them to confront the systems that strip people of their identities. It was a role that embodied his belief in the power of storytelling to change the world.

He truly thought that actors were no different from writers. They, too, told stories, but with their bodies. This is why he could never understand why performers weren’t given the same respect as authors under copyright laws.

Anyway, in the play, Sizwe Banzi is a man forced to bury his own name to survive under apartheid. He assumes a dead man’s identity, trading his past for a chance at a future. It’s a story about erasure, about the lengths people go to survive in a world that denies their humanity. And yet, there’s a moment of twisted triumph: Sizwe receives a wristwatch, a token of recognition for his years of labour. It’s a bittersweet victory—a symbol of survival but also of the system that forced him to erase himself to earn it.

I think Uncle Lari understood that irony deeply.

Years later, in 2009, he received his own recognition: the Member of the Order of the Federal Republic (MFR), essentially a medal awarded for his contributions to Nigerian arts and culture. For me, it was a real ‘Old Man and the Medal’ moment. He loved that medal. He’d polish it from time to time, making sure it flashed like a mirror in the sun. But, like Sizwe’s wristwatch, it was a bittersweet honour. He was grateful, of course, but he also knew that medals and awards couldn’t fix the systemic neglect of Nigerian artists.

‘We keep on keeping on like true artistes,’ he wrote many times in his Vanguard newspaper articles, ‘but what we need is more than applause. We need support. We need investment. We need a stage that doesn’t crumble beneath our feet.’

He fought to preserve the National Theatre, warning against selling it to ‘a bunch of traders who might want to build stalls for Tokunbo goods.’ Yeah, no, he wasn’t always diplomatic when he championed the cause of Nigerian artists, urging the government to recognize their value and invest in their future. For what he believed was good for the arts, he wasn’t always diplomatic even with his colleagues, making enemies left, right and centre. As the first president of the Actors Guild of Nigeria, I thought he was a terrible politician. I mean, how can a contrarian full of contradiction and paradox make a good politician? For example, his unwinnable fight against the name ‘Nollywood’ sent ripples through the industry. His ideas for the industry remained in a file he carried about until his death. Nonetheless, through his art and his activism, he reminded us that storytelling is not just a profession; it’s a calling, a responsibility, a lifeline.

Life imitating art? Perhaps. Or maybe it was art imitating life. Either way, my old man understood that the two were inseparable.

Here’s a poem about actors I sent to him in 2015:

Dear Actor,

Be yourself

Do what you’ve been called

To do

You’ve been called to be:

Others.

When I am acting

I’m not acting

I do not pretend,

I become.

There’s a difference

I become someone else

Sometimes, something else

I leave myself

On an old dusty shelf.

And this is when I’m

Being myself

But when this is your life

For very many years

It’s easy to forget

Yourself

But don’t be scared

Be yourself, Actor

Do what you’ve been called

To do

But prepare yourself

An actor must prepare;

For what this art

Could do to you.

No applause. He hated it, of course. Called it forced (without remorse). (Pardon me, couldn’t help myself). I agreed, still do. I do not have his curse of always hesitating to publish things, so I’m rarely afraid to put things out. Maybe that’s a curse, too.

In the end, the characters he played were never just performances; they were reflections of the world he lived in. As the native doctor, he confronted the superstitions and fears that have eroded Nigeria’s cultural heritage. As the cleaner, he celebrated the dignity of labour—including the labour of being an artist—and the quiet resilience of those who rebuild their lives from the ashes. And as Sizwe Banzi, he was a man fighting to reclaim his identity in a world determined to erase it. Together, these roles paint a portrait of a man who saw Nigeria not as it was, but as it could be: a place where history is honoured, labour is valued and stories are never forgotten.

You turned less into a legacy, Uncle Lari. And you never feared the fall. After all, what’s a curtain call but another beginning? The show must go on, right?

I miss you terribly, my old man.

I wish things were much better for you. For us. I wish I did more for you.

I thank you for your sacrifices.

You spoke often of artists dying Dickensian deaths. Yours was foreshadowed in many ways. I know that’s not really what you wanted. Knowing that—that you saw it coming— is what tore me to pieces.

Uncle Lari, what is death like? You promised you’d tell me. Was Wislawa’s take right? Is it like she described in her poem? Inept?

By the way, now I agree with your contrarian view: you don’t need family, you just need to love and be loved. But I’ll add that if you find that within your family, bonus points⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N2 Who Dey Fear Donald Trump? / Africa In The Era Of Multipolarity

₦40,000.00