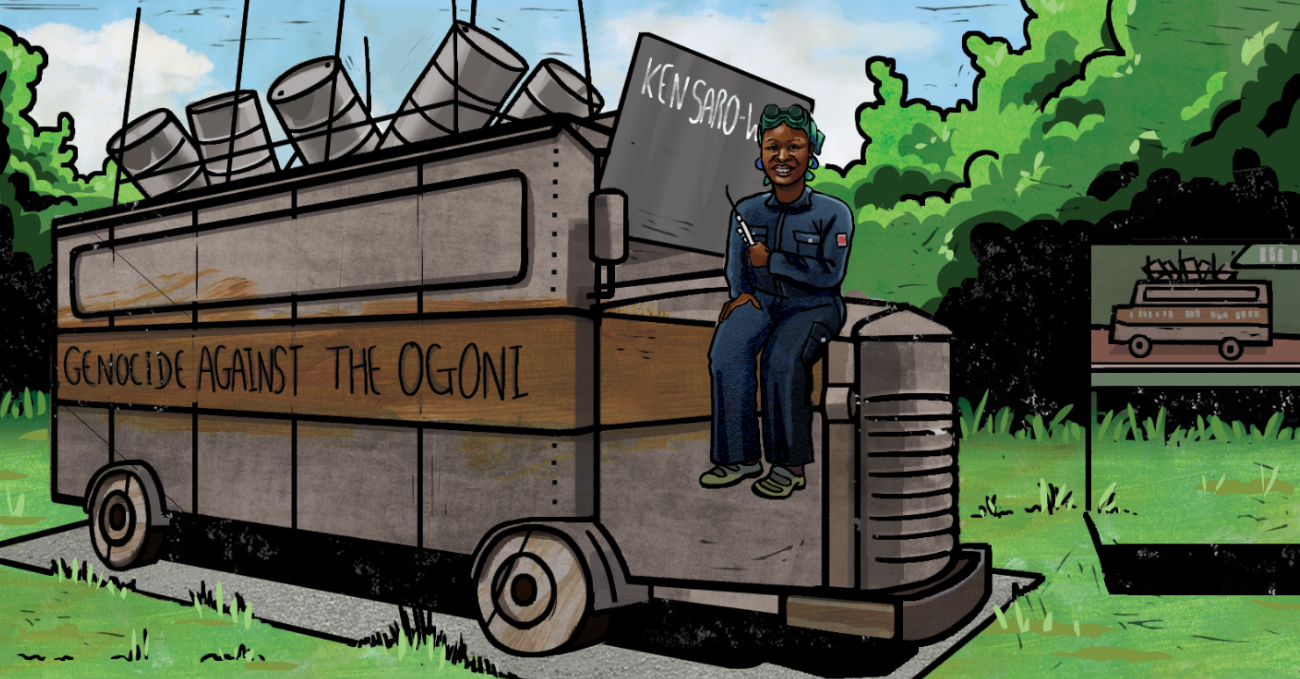

Illustration by Charles Owen / THE REPUBLIC.

THE republic interviews

The Artist Who Terrified the Nigerian State

Illustration by Charles Owen / THE REPUBLIC.

THE republic interviews

The Artist Who Terrified the Nigerian State

Public memory shouldn’t be controlled by the government,’ the Nigerian British sculptor, Sokari Douglas Camp, told me. It was April 2024, and we were in the verdant rooftop patio of her London home and studio. It was a rare, sunny afternoon for that time of the year, and she was having some renovation done, which meant the soft-spoken artist and I would sometimes pause for a wave of clanking to pass to keep from straining to hear one another. I was on the European leg of my research for season two of The Republic’s podcast on Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni Nine. One argument I planned to explore on the podcast was that the Ogoni movement was not remote but had profound international ramifications. What I couldn’t figure out, though, was what exactly the Ogonis’ international reach looked like, and the implications such a reach had on their relationship with the Nigerian government. While I knew that the Ogonis had been persecuted by the Nigerian state after the execution of the Ogoni Nine in 1995 (with many becoming refugees in nearby countries), it wasn’t clear just how prolonged and multi-faceted the state’s repression of the Ogonis was.

Enter the Battle Bus.

In 2006, the human and environment rights organization, Platform, commissioned Camp to create a work of art to honour the memory of Saro-Wiwa. Camp, who grew up in Port Harcourt and is herself from the Niger Delta, created a life-sized replica of a Nigerian steel bus, called ‘Battle Bus: Living Memorial for Ken Saro-Wiwa’; a work as striking in form as it was in political force in challenging silence and honouring the lives erased by environmental injustice. ‘It was an artistic symbol,’ I explained on the podcast, ‘of movement and change.’

In the years that followed, Camp established herself as an artist whose powerful sculptures—often forged in steel—channelled beauty, strength, memory and resistance. No surprise then that in 2015, 20 years after the Nigerian state had executed the Ogoni Nine, Platform wanted Camp’s Battle Bus to feature at a commemorative event in Bori, Saro-Wiwa’s hometown. But when the bus arrived at the Lagos seaport that year, it was impounded by the port authorities. ‘The head of Lagos Port said that he wasn’t going to let the sculpture enter and he basically arrested a work of art,’ Camp recalled. The bus never made it to Bori and has been missing ever since.

Back in London, our conversation spanned both the personal and the political: Camp’s Kalabari roots; the formative years she spent shuttling between Nigeria and the UK; her artistic philosophy; and the emotional weight of creating a memorial for Saro-Wiwa. ‘Anything romantic about Nigeria died,’ she told me remembering the day Saro-Wiwa was killed, ‘I was that upset.’ In many ways, the Battle Bus was her means of processing and articulating what Saro-Wiwa’s death had meant to everyday Nigerians; a way, too, of confronting the protracted injustices Saro-Wiwa and many from the oil-rich Niger Delta had endured and resisted. Years after the execution, nobody expected that a piece of art that sought to memorialize Saro-Wiwa would be detained at the ports. ‘It happened because the man who runs Lagos port was one of the judges that sentence the Ogoni 9,’ Camp revealed, ‘and it must have been like the people who were sentenced came back to life.’

Nigeria, like repressive states tend to be, is terrified of its own public memory, especially when such memory speaks to its legacy of violence. ‘No victor, no vanquished,’ the philosophy that became the state’s modus operandi following the Nigerian Civil War soon betrays its true purpose, which is not to seek diplomatic resolution as ostensibly purported, but to institutionalize silence. A symptom of our leaders’ prolonged inability to imagine a just Nigeria. So, when Camp’s Battle Bus was impounded on the grounds that it might incite violence in Ogoniland (never mind that the Ogoni movement was peaceful but brutally repressed by the government), it was an instance of the state’s totalizing fear of confronting its own violent history. ‘I just wish that the people that govern us were a little braver,’ Camp said.

Our full conversation continues below, edited for brevity and clarity.

WALE LAWAL

You have mentioned that you were born in Buguma in Rivers State. Did you grow up there as well? Can you tell us a bit about your background and what drew you to creating the Battle Bus?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

I was brought up between England and Nigeria. I was an airmail child, meaning I went to boarding school in England and was trafficked back and forth. I was born in Buguma, River State, and I’m Kalabari. I got involved with the Battle Bus because of a competition, and the competition wanted to make a memorial for Saro-Wiwa. Saro-Wiwa was known as a writer and environmental activist, but I knew him as somebody that wrote sitcoms for television and had done a lot in Port Harcourt to organize housing and just kind of management of life in Port Harcourt after the civil war.

He was a very conscious man who was very respected, and he was a writer. He was the first person to write a book in Pidgin English. And that shouldn’t be forgotten, really, because this man was aware of change like Chinua Achebe and was very inventive and seems to have passed this on to his children, his family and the rest of the world. He is now, or should be remembered as, Africa’s first environmental activist as well—the world’s first environmental activist that happened to be an African. And I was wanted to make this memorial because he was killed, and I couldn’t believe that such a gem was killed by the (Sani) Abacha regime back in the day. It was just such a shock, because Nelson Mandela had been let out of prison and Saro-Wiwa’s son, Ken Jr, was on television running around, meeting Mandela and other world leaders who were welcoming Mandela.

There was a buzz Mandela had at the time. Obviously, he came out of jail and was very important to the continent, and now a son from the same continent was about to be killed. So, it was a pivotal moment in 1995, and I just didn’t forget that, just because it was something to do with Nigeria. So, when the call out came to come up with ideas for remembering Saro-Wiwa, I thought I would try this. But I was actually scared because I thought of the power that killed Saro-Wiwa, who was a superstar and well connected, and then… myself, who isn’t well connected and a woman to boot? I just thought this is a little bit scary, just because as an artist, you can be politically aware, and we are politically aware as human beings. It is just that not all of us have the opportunity of expressing it, unless we go into politics or something, but artists have this license where they can say things. So, I thought I’d give it a go and I was one of the winners of the competition. The other winner was an Indian artist, and his name is Siraj Izhar, but he was unable to carry out his commission because one of the sponsors who would have looked after the costs died, and that was Anita Roddick, the Body Shop woman. But the whole thing was organized through an organization called Platform, who joined with PEN to commemorate and make a memorial to this fantastic man who they felt shouldn’t be forgotten.

WALE LAWAL

Before we talk more about Battle Bus, I wanted to just talk maybe a bit briefly, about the context in which Saro-Wiwa’s activism was happening. This was happening in the military era. If we look at the execution and the trial, it was happening specifically during the Abacha regime. As someone who was living in between the UK and Nigeria, what was the kind of impression that you had of Nigeria of that time? What did the military era feel like? What did the Abacha regime feel like?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

We are always hoping for the best for Nigeria and whoever comes into power, whether military or civilian, you just think, okay, try, for us, you know. We had been through an era in the (19)80s where it was just coup after coup after coup. So, we were thinking maybe a little bit of stability here with this man, Abacha. But he was different in that he went after the press. It was just a surprise because, pen and gun, who is going to win? It didn’t seem logical. His rule did not seem logical. And in visiting Port Harcourt, where I’d go straight away, because that is where my family were, I noticed that on Aba Road, towards the Port Harcourt University campus, someone who was a little challenged had painted words on walls, lampposts, huts, trash or whatever. But it was perfect text, because he was obviously someone that had a breakdown of some kind, and he did perfect graffiti. It seemed like such a rebellious statement to the government at the time because they were cutting what people could say. They were cutting down on our freedoms. And this person who was having a breakdown just covered the street in words that went on for miles and I just thought, visually that was exciting for me. Thinking, well, this man obviously doesn’t care and is trying to embrace the freedoms that one can have in one’s own country. And that is to speak out with letters. So, at the time in Nigeria, there was fear and repression and little outbursts from people, even madmen, that I saw as an artist.

WALE LAWAL

From what I understand then, we can kind of say that what Saro-Wiwa was doing at that time, being very vocal about the environment, was something that would have gotten people’s attention. It wasn’t something that a lot of—

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

—I’ll have to stop you there. Because it wasn’t so much the environment, per se; because all these environmental concerns have turned into big words that kind of locks people in. This was a guy that was very conscious of his home and realized that the way that oil was being extracted and the respect that was being shown to his community just wasn’t there. So, it wasn’t kind of environment first, per se, it was, treat my people better. Why are you acting in this way? We are people like you’re a person. Yes, the country has to make money, but they don’t do this in the North Sea.

And then, I noticed that my hometown had six flare points that had appeared, and so we didn’t have nighttime anymore. A bit like you don’t have nighttime in a city because there’s electric light. But there used to be a time where we could stay on our family balcony and watch the sun set. Then we couldn’t; the sun didn’t set because the flares were just there, lighting our environment constantly. And then the other thing we noticed was that there was more soot in the air than you would find in a London Underground or in New York where you go outside, walk around and there’s soot up your nose because of the traffic and stuff. You got that in my hometown, which is rather small, and we didn’t have many cars at the time because we didn’t really have roads. Travel was done by boat, and you would blow your nose like you had been in the subway.

WALE LAWAL

And the water in your hometown?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

Well, the water in Buguma was always sweet. Tasted good. But what happened was that, for some reason, the oil companies thought that they should make canals that would speed up the flyboat way of getting to the various islands, because my people live on 22 islands. And so, they made these canals that were just so deep that in some areas, sharks were able to come from the sea into the riverways. We had quite an innocent way of living. We had healthy mangroves. And yes, the place was tidal, and we had kind of black, fibrous banks for the mangroves to grow on. It is not the Caribbean beach kind of area, although we do have some beaches. But the Delta has these layers of soil and silt, all kinds of things, being part of our environment. So, part of our soil is black. We have these beds that are black, and white roots of mangroves in the area quite full and lush. But with the pollution, the mangroves started to die back. And then with our version of area boys, passage on speedboats wasn’t working out either. But now we’ve got roads. So, in an environment where you knew everybody, now we have strangers, which is sort of normal in most of the world, but as island folk, no, it’s not normal. You would recognize everybody at one time, but I suppose the chiefs and others think that it is quite a good thing that we are kind of more commercial. But some of the beauty of the past is gone.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00

WALE LAWAL

And do you think that you can trace that kind of commercialization, almost like a mechanization of the community, maybe through or due to the gas flares that have emerged? Are they all connected?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

They are all connected. We’ve had that context around Saro-Wiwa. We talked about the fact that he was advocating for his ethnic group or for minority ethnic groups. To me, that is a kind of a fascinating thing. I have listened to a lot of his speeches; if we have some time, there are a couple that I wanted to get your reactions to. But there’s somewhere he was talking about how Nigeria is not a true federalist state, because you do have a lot of it is concentrated around the three most populous ethnic groups. And he starts to really push for the fact that we have over 250 ethnic groups in Nigeria. You have Nigeria carved out to serve the three most populous groups and then everybody else is just kind of jumbled up into these other groupings.

WALE LAWAL

As someone who saw some of Saro-Wiwa’s activism and listened to some of his speeches, what would you say made him compelling to everyday people?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

Maybe what was remarkable about Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni 8 that died with him was that they were educated people. Our military leader at the time wasn’t necessarily an educated man, not the same kind of calibre, really. And yes, Saro-Wiwa was very good at talking about his people, the Ogoni, who were considered a minority group. But in Nigeria, who really considers themselves a minority group? You’re born thinking you’re that person [laughing]. So, I think he was advocating for all of us because he was a bright man that found wit in an awful lot of things, just because we were children of the (19)60s when Nigeria was trying to find its feet and Saro-Wiwa just cared about the country. And I didn’t know the guy. I wasn’t political, but after the war, I know that my people, who were considered another minority group, were helped by properties and all sorts of things being fairly shared in Port Harcourt. With the war, they just tried to make politics and policies more equal in Port Harcourt and Saro-Wiwa was part of that. So, of course, some people didn’t like him for that, because it was almost like sharing people’s wares after the war. But he tried to create some kind of community with all the different ethnic groups that Port Harcourt has—a very different approach from the regime that killed him. They had other ideas, and I think theirs was just about ruling rather than caring for the environment or the people in Nigeria.

WALE LAWAL

A very important point that you have made is what counts as a minority group in Nigeria. Minority is a term that the government throws at us, but it is not a term that we grew up internalizing. I think a lot of people, at least nowadays, feel like we do have questions around what you know, what makes us Nigerians, what connects us. But everybody thinks they are the centre of the world. And I think that’s a point that I truly agree with. What I have struggled with in understanding Saro-Wiwa’s legacy is the fact that a lot of the history books try and paint it around minority group advocacy. But you can actually see across board, across Nigeria, that the issues that he was raising resonated with people, regardless of where they were from. He was talking about things like government neglect. He was talking about the government putting profits over people. These are things that the general working-class people in Nigeria all experience.

What is also really interesting to me about that kind of thinking is when you have authority figures in Nigeria, we tend to have people who weaponize ethnicity. They use it to say, ‘Oh, don’t vote for this person because they are not from your tribe.’ Saro-Wiwa seemed like he was challenging that. Then he was accused, or at least him alongside the other eight—Saturday Dobee, Nordu Eawo, Daniel Gbooko, Paul Levula, Felix Nuate, Baribor Bera, Barinem Kiobel and John Kpuine—were all accused of the murder of four chiefs. Obviously, they denied those allegations. There is a prolonged trial that ends in them being executed. As someone who is not political, what did it feel like to see that trial play out? What did it feel like to experience it end in an execution?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

At the time? Pure panic. You just thought, how is it going to end? How is it going to stop? Nine people! And the thing was that these weren’t the kind of people that would preoccupy themselves as planning murder. They were busy doctors, lawyers, teachers, writers. It is not the first thing that would come to an intellectual’s mind to go and organize the murder of a local chief. Really, you just thought, are you crazy? Why would they do that? But the longer you live, the more you think anything crazy could have happened, really. I mean, change of information, manipulating information. But I think back in 1995, the times were more innocent. I think life was a little more direct. These people campaigned against the government, and then this idea was planted on them, I think, because as a working person, you don’t have the time for some extracurricular activity like planning a murder. It just really takes a lot of time—on top of writing sitcoms on television, making sure your children were alright, getting your daily bread, you know, running your family—to plan to murder a couple of chiefs. I would say that I think a lot of people didn’t believe it, for the simple reasons that it would be totally unreasonable for these men to plan something like that because it had nothing to do with their campaign. I think they were more into discourse than murder. So, when these powerful men were killed, I really thought Nigeria had lost the plot. It affected my work. I decided that anything kind of romantic and wonderful about my country was dead. I was that upset.

WALE LAWAL

And then there’s all this push from both local and international organizations calling for the government to show clemency and to not proceed with an execution. But then, of course, the execution happens. What did it feel like back then?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

It was horrible. I can’t explain how horrible it was for a country to kill its own sons. Back in the day, to be educated enough to become a doctor, lawyer or whatever took so much sweat for parents. And for the people that actually got those qualifications, you just thought, if you can waste people like that as a new nation, what kind of nation are you? It was terrible. It is terrible.

WALE LAWAL

Around a decade passes and then you have that competition, and you decide to produce ‘Battle Bus: Living Memorial for Ken Saro-Wiwa’. I want to stop there for a moment and just think through: were there any other like concepts that you thought about? How did you arrive at the concept of the bus?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

I think my work is very intuitive. I have a lot of things in my head, and at the time, to make a commemoration of an environmentalist with a bus is a strange idea. But the thing is a battle bus is something that all politicians use worldwide. They have a banner. Donald Trump, Barack Obama, all these people have a tag on a bus. In Britain, it was all those Brexit lies that we had. Those were battle buses. So on the commission brief was to think of something that could travel and campaign in different spots, because they didn’t have a site for this memorial in London or anywhere in England. To have something as mobile as a bus seemed okay. I love the fact that you have funeral buses and things that will truck through town with banners and people hanging on the side saying, ‘Oh, this person that’s gone is the most powerful, wonderful person.’

We use buses in lots of different ways, and also the fact that, on the continent, we doctor vehicles in the most remarkable way. You mean putting a load on that would be so tall that there’s no aerodynamic anything about the vehicle anymore. It has been manufactured in a German factory to just let breeze pass easily. And then it goes to the continent and a pile of grain goes on top of the lorry. And then there are people on top, there are bags of grain. So, it’s the load. I wanted to talk about load, a heavy message. I wanted to talk about this battle bus and politics. I wanted politics to be a thing and the words on the vehicle too, for instance, when you have Trump and all these noticeable things on the vehicle. I wanted wording on the vehicle. And I had been listening to a lot of Saro-Wiwa’s interviews. So, I came up with a bit of conversation that said, ‘I accuse the oil companies of practicing genocide.’ I don’t believe those were the exact words, but they were near enough.

I remember my shock, thinking that this man mentioned genocide with the companies that worked in the Niger Delta, because I never thought that they were actually trying to kill us. I just thought they were behaving badly, because the West behaves badly. But yes, it is a form of genocide to pollute an environment so much that people can’t go home or to disrupt an environment so much that young men have to kidnap other people to survive. It is quite a thing that doesn’t encourage you to go home, that doesn’t encourage you to stay at home. So, what’s happening? A clearing is happening, and that was the beginning of things in the late 1990s, people wanting to leave the Niger Delta and so the words on the bus were incredibly important, and the bus itself was actually empty. It was an empty vehicle, and it had a banner at the front that would be very like the way people in Port Harcourt have white as a way of catching attention because it is a busy environment. When there is something white, you will turn to look because it is like an alarm, more so than red. Here in London, it is red. In Port Harcourt, it used to be white. So, there is a white banner at the front and the oil barrels on top of this battle bus that I made. The names that you just mentioned. And you know, it was amazing to cut out the names of these men that were tied in with Saro-Wiwa so much that they were killed at the same time. It is almost as painful as making a crucifix. These people, did they die for us? They did, and it is just tragic, really. They must not be forgotten.

WALE LAWAL

Could you talk a bit more about how you created the bus?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

Oh well, the bus looks like a bolekaja, which is a kind of Nigerian signature. I mean, there are so many different types, and it is made of stainless steel, quite thin stainless steel, but stainless steel is strong. You know, we all have stainless steel knives and forks, so it doesn’t rust. And what I did was to have brass and copper sprayed onto the side so it looked as if it was inflamed, a bit like the flare stations that you can see. If you go to see one, you see a flame and it has brass, yellow, copper, lead and smoke coming from it. But my artistic version is this kind of clouded area in the middle of the bus where the words are, which is brass and copper, and is sprayed onto the stainless steel and then buffed up. And it is quite impressive and worked well. The lettering is cut through the sheets of steel so that you can see through. You can actually go up and put your eye up to the lettering and see into the dark crevice of the bus, which has no lights or anything like that. It is a sculptural structure, no engine. Other artists have taken incredible pictures of the lettering, which reflects itself into the inside of the vehicle and also reflects the right way around. You know how you look at something in the mirror, and the lettering is the wrong way around. This is a reflection that is the right way around inside the structure of the vehicle. I’ve never felt prouder, just because it is a memorial to a writer and the writing is inside, swimming around as if there is a conversation going on in there, which wasn’t planned. And you know when you see it, you can actually see the lettering reflected the right way around. The other thing about the idea of a battle bus is that it is also like a library bus that some communities have, where a bus will come and park in a local close or something, a bit like an ice cream van. And it will rest somewhere, and people can go and pick out books. That was one of the ideas, that this was like a library vehicle. Other artists used it as backdrops to play music because they came from the Niger Delta. Other activists just used it to educate children about what happened to Saro-Wiwa who was a writer. Then they found out about the Ogoni 8 that died with him, and it was just a way of conveying and sharing our history to the British, some of whose interests in Nigeria made this happen to our community. It was very important to let people in Britain know the part they played in Saro-Wiwa’s death.

WALE LAWAL

How did the bus get to Nigeria?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

Well, the organization, Platform, made this happen. They are an organization that are very conscious of the environment. They are environmental campaigners, and it had been 20 years since Saro-Wiwa and the other Ogoni Nine died and they wanted to get the bus to Nigeria to celebrate 20 years since Saro-Wiwa had passed. And the idea was to get this sculpture to Bori, his hometown, to site it there so that people would not forget, and people would keep on campaigning to save their environment and remember these men that put their lives on the line for their community. We raised money to get this work to Nigeria in 2015. And in 2015, the head of Lagos port said that he wasn’t going to let the sculpture enter and he basically arrested a work of art. It is 2024 now, and the work is still arrested, and whoever it is that’s running the country won’t let it out, even though they don’t have a right to do this because this is a work gifted to the people of Bori and it is an educational piece of work. There is nothing violent in it, even though it is remembering violence that was done to community we are hoping to repair and remember and educate. That was one of the reasons for sending this artwork to Nigeria, where it belongs.

WALE LAWAL

Could you talk a bit more about the text on the bus?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

On the bus, the text looks kind of very mechanical. But when it is abstracted, it can look like sewing and is quite effeminate. The text is created like this because of the font on the bus. A man called John Daniel has designed a font that you can find on Fontland on the computer that is called the Sokari Font. And it is actually the font from Battle Bus. I have used it on a book about my work. Daniel and Alfredo Jaar created this font to remember Saro-Wiwa and his politics, because he didn’t want people to just sit by and let things happen to them. It is a wonderful thing in the memory of Saro-Wiwa and we hope to get the bus out and continue the conversation that is part of our history.

shop the republic

WALE LAWAL

Let’s talk about the arrest of the bus. Why do you think that happened?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

It happened because I must have been rude. It happened because the man who ran the Lagos port was one of the judges that sentenced the Ogoni Nine, and it must have been like the people who were sentenced came back to life. And he was refusing to let their history and his actions come out. But really, he must be quite old now, he will go, and the bus will continue to live if he hasn’t destroyed it. But if he has destroyed it, I would like compensation for my work, please, whoever you are because you know it was hard work that made that piece of work that you find so threatening, and you find it threatening because of your guilt, maybe. Because, if you’re guilt free, this wouldn’t be a threat.

WALE LAWAL

What do you think that says about the nature of public memory in Nigeria? The fact that you have a memorial like this that is still, for so many years now, locked up or at least in suspension. It is kind of like Schrödinger’s sculpture. We don’t know if it is still existent or no longer existent.

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

Well, public memory shouldn’t be controlled by the government, really. If you were there and you saw it, you can’t erase it. It cannot be erased. And public memory is history. And yes, there are different kinds of history that are told, but I think that the majority of Nigerians are brave, fearless people. We believe in ourselves, and I just wish that the people that govern us were a little braver. You have to be brave, you have to be courageous, and you have to fight for us, not against us. And that is something that as a new nation, I think we have to keep on saying to the people that wish to govern us.

WALE LAWAL

I like that comment about bravery and about the kind of courage that you need as a leader, as a public figure to invite those conversations. They are very difficult conversations, but they are necessary conversations. But for us, it does feel like a pattern. It feels like a pattern in the way that we don’t officially memorialize the civil war in any capacity, or in any main or major public capacity. It also feels, even more recently, like the refusal to really acknowledge truly what happened during the #EndSARS protests. It all feels like this pattern in which the people who govern us are not brave enough to either be held accountable for their own actions while in office or to even invite discussions about who we are as a people, even when it doesn’t necessarily directly concern them. This is in the sense that you could have successive governments—you made a comment about how the ports officer will not be in office forever, but from what we understand about the way Nigeria works, even if he is not in office, someone, somewhere might still be committed to preventing that memory from being shared or being preserved in Nigeria. And so, it comes down to a question about imagination. What kind of society we imagine ourselves to live in, what kind of society do we imagine is capable of acknowledging really difficult parts of our history?

Something I find compelling about Battle Bus is that it invites a conversation around mediums. We could easily turn to books to find out about you or to find out some aspects about Saro-Wiwa or the Ogoni Nine execution. You could turn to video documentaries, the few that exist. But what is it about a sculpture that gets people uncomfortable? And the reason I ask this is, the same officer, the same governing officials that are saying, ‘Oh, we don’t want to let this in because it might trigger actions.’ It doesn’t feel like they feel the same way necessarily, about how people could easily go online and still read about it. They could still listen to documentaries about this. They could very well listen to this podcast in ways that are beyond the control of the government. There are people who have listened to these things and haven’t taken to the streets. So, I’m not convinced entirely by that argument that, by experiencing this thing, people will take to the streets. So why do authorities feel that a sculpture has this hold on people that maybe a book or a documentary may not necessarily have?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

I can’t answer that question, but there is power in art. You can express kind of pain and elation, peace and all sorts of things with a piece of art. And I’m not sure that Battle Bus is really in that category, but it has presence, and it talks about how we consume oil, the problem of oil, and it mentions the son of the soil, which is Saro-Wiwa. And then it has the names of the other Ogoni Eight. I guess their names are powerful. They are on an information vehicle that kind of resonates with the Nigerian environment, because it looks like a bus that we might jump on. But our government’s fear is kind of wasted because we’ve got to become more proactive with our young country. We have so much to offer and so much to remember and so much to acknowledge to be a better place for the future There’s nothing to be afraid of.

WALE LAWAL

So what comes after? Right now in Nigeria, in many academic intellectual, ideas and policy circles, we are all talking about the end of oil. We are looking at a future in which everyone is—on paper, at least—trying to move away from oil. What does that inspire you to think about? And I’m saying this particularly in the context of, we’ve reached a point with climate change where we know that—at least recent scientists have told us that—the impacts are going to be irreversible. We have had the red alert come in. We have also had at least pushback from governments on the continent who are like, ‘Look, oil is our best bet. Now that we are starting to get a hang of it is when you want us to find other fuels. What are we meant to make money on?’ Africa doesn’t pollute that much. We don’t generate that much in terms of carbon emissions. We still have room to explore fossil fuels even further. We don’t want to switch from oil because all of you have had your chance to develop, using these same resources, and now that it’s our turn, we are being asked to not do that. But then, of course, you have the communities that are caught in this crisis, who are losing ways of life, incomes, security levels deteriorating, quality of life deteriorating.

As an artist who is concerned about these issues, there are two questions here. The first being: how is your interest in all of this changing over time? Since Battle Bus, are there new projects that you are working on through which you are thinking about these issues in a different way? Are your thoughts about these issues changing? Are you more hopeful? Are you pessimistic about the future? With Battle Bus still locked up and with everything that we know that is still happening in the Niger Delta, where is that interest now?

SOKARI DOUGLAS CAMP

We have been superseded by concern about data. You know, oil was definitely a twentieth-century concern. Now it is data, but of course, the environment is still with us and damaged. In the Niger Delta, the sea level is going to rise. My hometown is going to be underwater. I was talking to my brother the other day and he was saying quite proudly that there are roads now that go to some different islands in our area and saying, wasn’t that wonderful? And I said, but you know, more roads means more polluting because they have this component of oil in them and tyres putting other kinds of fumes up into the environment. And I said, ‘Tim, we don’t always have to follow the West. We had it sweet before with water transport that took us from island to island because you knew the delta routes that would get you there.’ So for the future, I am hoping that we embrace what we know a bit more; because we have an awful lot to offer the world in that way. And our folks living with what they had, and farming in the way they knew, and fishing in the way they knew. Wasn’t that great?

Growing up, I realized that nylon upset communities in the Niger Delta so much because it was a thread that didn’t break. People used to have conversations about fixing nets at one time in our lives in the Niger Delta and that made us come together. We discussed what to do about life, but with nylon, you didn’t have to come together to fix anything. It was something that lasted to our detriment. So, I am hoping that we will appreciate our own knowledge a bit more.

I love the fact that in the diaspora—not just the diaspora actually, it is the world—an awful lot has come from Saro-Wiwa’s work in fighting oil companies, so much so that they have symposiums about his plight and the plight of the Ogoni Nine in Brazil. Little booklets have been written about how to campaign and how to talk to the government because of his example. That has happened without any kind of obvious campaign. It is just the information and an example is there, it is global. We have the internet nowadays. Like you said, you can look these things up. You don’t necessarily need a memorial bus, but a memorial bus was what started the conversation and encouraged these people in Brazil to do what they are doing, to look after their environment. And one thing that did make me incredibly aware of the environment was the fact that I sat in a dentist’s waiting room and opened National Geographic, and they said it was flaring in Nigeria that was creating a hole in the ozone layer in Australia. So that absolutely got me into thinking that this is a world problem, not only a Rivers problem, and it still remains that way with the environment, rising sea levels and the rest⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N2 Who Dey Fear Donald Trump? / Africa In The Era Of Multipolarity

₦40,000.00