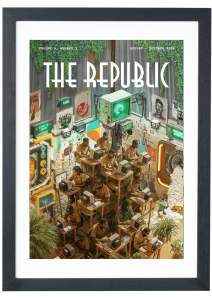

Photo illustration by Dami Mojid for The Republic. Source Ref: FLICKR.

the ministry of political affairs

APC’s Unspoken Rules of Fuel Subsidy

Photo illustration by Dami Mojid for The Republic. Source Ref: FLICKR.

the ministry of political affairs

APC’s Unspoken Rules of Fuel Subsidy

The voice of Ganiat Fawehinmi, the wife of the late eminent civil rights lawyer, Gani Fawehinmi, was loud on the third day of the 2012 Occupy Nigeria protest: ‘When you see Babangida,’ she said, ‘ask him where he kept our $12 million windfall. When you see Iweala, ask her if this is the way the government of where she came from treat their citizens.’ Eventually, she screamed, ‘If you see Diezani Alison-Madueke, ask her how she got the money to buy a house in Vietnam. God will punish all of them.’ The crowd she was firing at roared back too, with even more gusto. ‘If you no gree for ₦65 na war o, anything wey you want we go give you, na revolution go be the next step o,’ two men out of the sea of protesters declared matter-of-factly to the incumbent president, Goodluck Jonathan. All these people, perhaps over a hundred thousand, were tightly absorbed at the Ojota axis of Lagos, vehemently remonstrating against the official removal of fuel subsidy by the Petroleum Product Pricing Regulatory Agency (PPPRA) on 1 January 2012.

Following the PPPRA’s jarring announcement, the price of petrol had immediately increased from ₦65 to ₦141 per litre in filling stations across Nigeria. (In the shadow market, the increase was more like ₦100 to, at least, ₦200 per litre.) Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, then the governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), almost immediately justified the subsidy removal by contending that petrol subsidies cost the government $8 billion during the previous fiscal year and that the programme remained unsustainable given that subsidies should primarily cover economic production and not consumption. But the Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), the major opposition party, was eating up none of it. In a statement by ACN’s national publicity secretary, Lai Mohammed, the party averred that Jonathan’s removal of the ‘non-existent’ fuel subsidy was not in the interest of Nigerians since it came at a time when the majority of Nigerians were barely surviving. It concluded that along with a consortium of political parties, it had warned the government that existing refineries should be made to work before a removal of fuel subsidy could be contemplated.

The market price of petrol was eventually pegged back to ₦97 per litre due to the ripple effects from the ferocity of the nationwide protests, even as the government promised to continue to pursue full deregulation of the downstream petroleum sector. Yet a salient takeaway from the entire fiasco was not just the Peoples Democratic Party government’s timid inconsistency with regards to the administration of fuel subsidy. It was also ACN’s staunch resistance to the increment of petrol price through subsidy withdrawal. Did ACN ever put itself in the shoes of the ruling party and wonder how it would go about ensuring sustainable market sanity in the downstream petroleum sector? Did it earnestly consider if it would fix refineries before removing petrol subsidy just like it advised the ruling government, and would it obey the letters of the law if it directly prescribed unrestricted free market pricing of petroleum products in Nigeria? More importantly, a bigger question to draw was: what does fuel subsidy mean, not to the throng of Nigerian masses, but as a political issue to the political parties, ACN, now rebranded as part of the larger All Progressives Congress (APC), being a focal reference point?

THE MODERN ORIGIN OF FUEL SUBSIDY

Economic subsidies as an inflationary cushion in Nigeria found their legal roots in the late 1970s and early 1980s, following the passage of the Price Control Act of 1977 under the Olusegun Obasanjo military regime. Schedule one of the Act listed petroleum products as part of ‘controlled commodities’ that were not to be sold above a basic price. This policy of state sanctioned subsidy then teed up smoothly with the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) introduced in July 1986 by the Ibrahim Babangida administration following the collapse of oil prices in the first half of 1980s. The SAP sought to promote non-inflationary economic growth in Nigeria through a host of means, including using the pre-existing petrol subsidy to act as a temporary measure to control the prices of petroleum products while the refineries were under rehabilitation.

The payment of petrol subsidy for refined petroleum products for use in Nigeria soon continued unabated afterwards and most attempts to remove the fuel subsidy or to alter the benchmarked price of petrol products by successive governments were often met with staunch opposition by labour unions and citizens. This was the case when the Adams Oshiomhole-led Nigerian Labour Congress grounded the working economy to a standstill for eight days in June 2000 after the Obasanjo presidency increased the pump price of petrol from ₦11 per litre to ₦30.

Still, the modern history of what is colloquially known as ‘petroleum subsidy’ in Nigeria can be traced to the advent of the Petroleum Support Fund (PSF) in January 2006. The PSF was administered by the PPRA through guidelines that were publicly published, and its workings were fairly straightforward: a pool of funds was provided in the budget of the federal government contributed to by the three tiers of government so as to stabilize the domestic prices of petroleum products against the volatility of the prices of international crude oil and petrol products. Essentially, the government would use the fund in the pool to pay fuel marketers the difference between the expected market price of imported petrol and the government capped ex-depot retail price of petrol so that fuel will be relatively affordable for Nigerians. This expected market price of petrol factored in a range of costs, including product cost, freight, lightering expenses, depot charges, financing and distribution margins.

However, the devil’s favourite playground is often in the details, especially within the Nigerian context. Bribery, corruption and nepotism soon took hold of the system, to the point that the government did not know which fuel marketers it was paying the subsidy funds to, and how much exactly. A 2012 report by the House of Representatives’ Ad-Hoc Committee on the implementation of subsidy in Nigeria revealed that the federal government had paid more than 900 per cent in excess of the actual subsidy it claimed to have paid for the 2011 financial year. Thus, while the CBN claimed the federal government paid out ₦1.7 trillion as fuel subsidy for the year, the ad-hoc committee found that the government actually expended more than ₦2.5 trillion as fuel subsidy costs.

All these inadequacies in the administration of the fuel subsidy regime rightly led to calls for its removal or refurbishment. However, petrol subsidy soon had no more legroom to operate after many fuel marketers, the operating middlemen of the system, gradually discontinued importing refined petrol into Nigeria due to the challenges of FX scarcity and the rising cost of fuel importation, leaving the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) to be the sole importer of petrol into the country.

The passage of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) into law in 2021 by the Muhammadu Buhari administration ultimately settled the matter by forming the latest legal pronouncement on petrol subsidy in Nigeria. Section 205 (1) of the Act states that wholesale and retail prices of petroleum products shall be based on unrestricted free market pricing conditions, effectively removing fuel subsidy—at least in theory.

shop the republic

APC’S MORAL ABDICATION

If anyone thought that the ratification of the PIA by the Muhammadu Buhari presidency would settle the muddy waters with regards to fuel subsidy administration in Nigeria, they would have been in for a rude shock. While Section 317 (6) of the Act explicitly maintained that the NNPC should only cover the cost of petrol supply and distribution in Nigeria for a period not exceeding six months of the passage of the law, the APC-led government still continued to maintain the subsidy programme for political purposes. In fact, the approach of the Buhari administration to total fuel subsidy removal as envisaged by the Act can be summed up in the last two paragraphs of a statement released on X by his official spokesperson, Garba Shehu, in June 2023:

Finally, we must be politically honest with ourselves. The Buhari administration in its last days could not have gone the whole way because the APC had an election to win. And that would have been the case with any political party that was seeking election for another term with a new principal at its head…Poll after polls (sic) showed that the party would have been thrown out of office if the decision as envisaged by the new Petroleum Industry Act was made.

Just a month before the expiration of the six month window of subsidy payment granted by the PIA, Timipre Sylva, the minister of petroleum, curiously proposed an 18-month extension to the national assembly for the actualization of the subsidy removal implementation period—the government then paid ₦4 trillion for subsidy in 2022 and another ₦3.6 trillion for the first six months of 2023. In total, APC’s Buhari outspent his three democratic predecessors combined by paying out about ₦11 trillion on the same ‘non-existent’ subsidies the party had initially accused Jonathan of also spending on. The petroleum refineries the party advised Jonathan to fix before removing fuel subsidy also remained moribund even after the government spent over ₦1.4 trillion on them.

Mele Kyari, the group chief executive officer of the newly incorporated Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation Limited (NNPCL)—which legally overtook the NNPC, Nigeria’s former state oil company, and was now vested with a mandate to declare profit following the enactment of the PIA—would later publicly admit in June 2023 that by the operation of the law, the subsidy regime in Nigeria effectively ended on 22 February 2022, following the expiration of the six month subsidy payment period granted by the PIA. He added that the government only kept paying for fuel subsidy because ‘the government can always decide to spend on its citizens, in the manner that it wants.’ However, the final context that Kyari failed to include in his admission, which Shehu did, was that the APC government kept subventing petrol for Nigerians, especially during its last 18 months in office when it wasn’t fiscally agile to do so; because there was an election around the corner and the party needed to win the polls by papering over many subsidy-related cracks as a decoy to save face with the public.

The electricity subsidy that was initially claimed by the National Electricity Regulatory Commission to have been removed under the Buhari presidency was debunked by the new minister of power, Adebayo Adelabu, in April 2024. He confirmed that it remained operational as the Buhari administration failed to stop paying petrol subsidy even after the PIA charged it to do so and after it vigorously promised in its 2013 manifesto to reform the oil and gas sector, establish modern oil refineries to increase the flow of oil and gas products to domestic consumers and improve the domestic oil and gas supply chain.

Given the facts, fuel subsidy can be summed up as nothing but another campaign rhetoric in the hands of APC, ready to be manipulated at any time to whip up the primordial sentiment of its campaign base and get the hopes of Nigerians flying. The Bola Ahmed Tinubu presidency did confirm on its first day in office that subsidy payment was ‘gone’, but as we can now see, this was a well-timed declaration given that APC had finally won the election and was replete with freshly given political capital. Even so, the subsidy Tinubu announced as removed was already not factored into the budget by the Buhari presidency for the second half of 2023 since Sylva only sought subsidy extension from the national assembly for the last 18 months of Buhari’s tenure.

What’s more, the Trade Union Congress and the president of the Petroleum and Natural Gas Senior Staff Association of Nigeria, Festus Osifo, claimed in October 2023 that the Tinubu administration still covertly pays the petrol subsidy despite the government’s position to have disavowed from doing so. Gabriel Ogbechie, the chief executive officer of Rainoil Limited, also re-echoed Osifo’s sentiment in April 2024 by maintaining that with a daily fuel usage of around 40 million litres and an exchange rate of ₦1,300, the federal government, through the NNPCL, still pays between ₦400 and ₦500 per litre on fuel imports culminating in a monthly total of approximately ₦600 billion. This way, Nigerians can pay for fuel at around the ₦500 to ₦1000 price range, even though the NNPCL has vehemently denied this postulation.

NIGERIA’S FEDERALISM: WHO BENEFITS MORE?

Nigeria’s federal system, established in 1999 after decades of military rule, divides power and resources between the federal government, including the Federal Capital Territory, and 36 states. This structure, while aiming to foster regional autonomy and development, has become a source of contention, particularly when it comes to issues like the minimum wage.

On one hand, fiscal federalism in Nigeria allows states some control over their economic destinies. They can prioritize spending on areas crucial for their development, such as agriculture in agrarian states or infrastructure in urban centres. This allows states to tailor policies to their specific needs and economic realities.

On the other hand, states do not enjoy true fiscal federalism as the federal government controls the bulk of national financial resources including payment for crude oil or other natural resources explored from these states. The federal government then gives out a statutory monthly allocation to state and local governments using a derivation formula.

The current federal system in Nigeria also creates significant disparities. Wealthier states, particularly those rich in oil resources, have greater financial autonomy and can afford a higher minimum wage for their workers due to the 13 per cent derivative fund. These states usually attract businesses and skilled labour, further widening the economic gap between them and non-oil-producing states. Furthermore, weaker states with limited tax bases struggle to meet their basic obligations, including paying a national minimum wage, hindering their ability to attract investment and improve living standards for their citizens. Hence, a single national minimum wage might not be the answer in a country as diverse as Nigeria.

shop the republic

FORESTALLING A HAPLESS FUTURE OF ENERGY INSECURITY

Indubitably, the ultimate solution for greater efficiency in Nigeria’s downstream energy sector is for the country to fix its refineries to the extent that they have the capacity to handle crude oil refining at a substantial level enough to power the working economy. An intermediate option would be for it to reduce the volatility in the workings of its exchange rate by increasing its foreign exchange earnings so that the expected market price of imported petrol into the country is affordable for the average Nigerian. Data from the Nigerian Bureau of Statistics released in February 2024 showed that the NNPCL imported about 12 billion litres of petrol in the first half of 2023 while spending about $7.7 billion as the total fuel importation cost in 2023. This is because Nigeria has the lowest local refining capacity among the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries members. Nigeria’s refineries are only able to serve less than ten per cent of the 66 million daily domestic petrol demand leaving 90 per cent of petrol needs to be met only through imports.

Regardless of the dire petrol dynamics, the market functioning of fuel has only gotten worse since the oncoming of the APC administration in 2015. Buhari attempted to sweep many challenges in the downstream petroleum industry under the carpet by timing the 18-month subsidy extension (from the expiration of the six month subsidy window granted by the PIA) to exactly run out at the end of his tenure. This policy move inadvertently led Tinubu to make a Freudian slip on his inauguration day by declaring subsidy ‘gone’ and giving a statement on subsidy removal that was not included in his swearing-in speech. Tinubu’s pronouncement has further created a peculiar fuel crisis laden with panic, fuel shortage and petrol price surge coupled with heavy forex difficulties and the growing disinterest of more than 200 fuel marketers to reduce petrol shortfall and invest in petrol supply and distribution. That petrol supply (and necessarily demand) has reduced by about 50 per cent in the past year in what should be one of the fastest growing economies in the world is not favourable.

The commencement of petrol refining at the Dangote refinery should play a considerable part in improving the efficiency in the downstream petroleum sector. It should also help reduce the arbitrary price of petrol since the facility has the capacity to refine about 650,000 barrels of crude oil per day into various fuels including petrol and another 4.78 billion litres of storage capacity for refined petroleum products. Also, if the projection in May 2024 by Ifeanyi Ubah, the Chairman of the Senate Committee on Petroleum (Downstream), that the Warri and the Port Harcourt refineries will become operational later in the year and the Kaduna refinery will do the same in 2025 is anything to go by, then a fortuitous turn may be on the horizon for Nigeria’s efforts in domestic petrol refining and self-sufficiency. Due credit must be given to all the governments that have been in power during the developmental life cycles of these projects, including those of APC. Stimulating local content value addition in the petroleum industry will reduce the pressure on foreign exchange, which will in turn strengthen the parity of the naira and bolster the economy. Yet, it is in summoning the political will to truthfully address the entrenched clogs in the workings of the petroleum industry in an altruistic way that is devoid of short-term political benefits like harnessing the next electoral votes that many Nigerian governments have struggled with. The two recent APC-led governments are only the latest casualties⎈