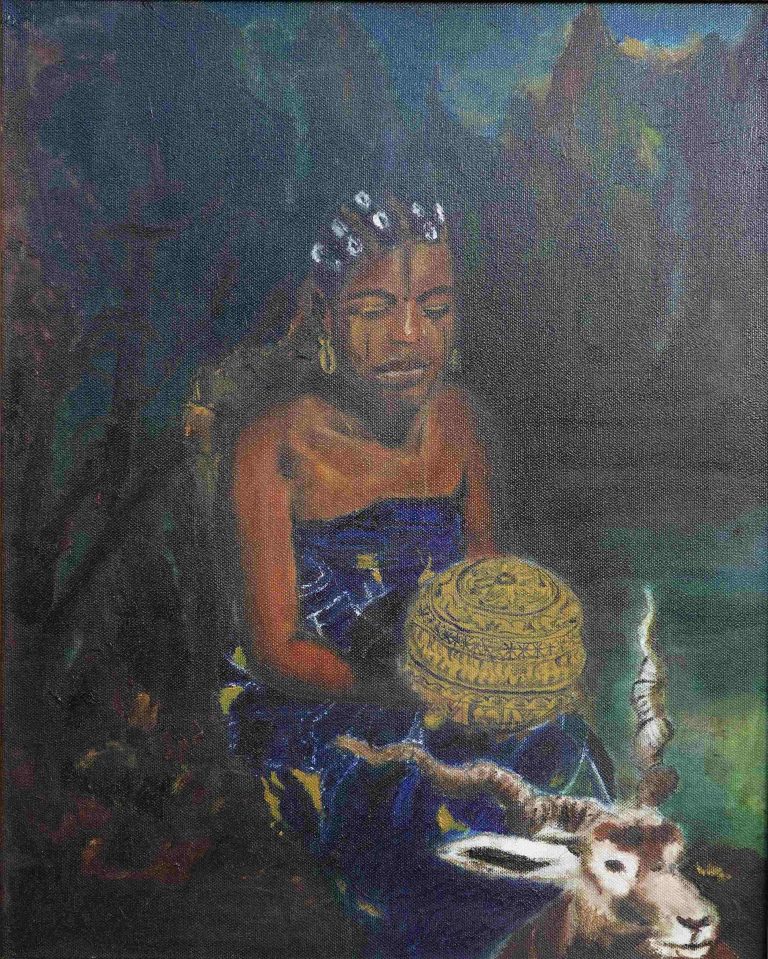

Femi Bajulaye’s ‘Ekun Omi Tears of desert water’, 2025 / IMDB.

THE MINISTRY OF ARTS / FILM DEPT.

Èkún Omi and Femi Bajulaye’s Yoruba Aesthetic Vision

Femi Bajulaye’s ‘Ekun Omi Tears of desert water’, 2025 / IMDB.

THE MINISTRY OF ARTS / FILM DEPT.

Èkún Omi and Femi Bajulaye’s Yoruba Aesthetic Vision

When Femi Bajulaye started writing a couple of short stories and developing a series of paintings, making a film wasn’t the active and primal intention. Then, in 2016, he was responding to the growing number of Africans leaving their countries illegally due to the social, political and economic uncertainties. This economic and political crisis inspired Èkún Omi: The Fatigue of Black Anatomy, one of the paintings he created during this period. As the multidisciplinary artist told me in a recent interview, the painting served as a catalyst for understanding the political effects of migration. As a Nigerian migrant himself, to continue the conversation around migration in his artistic work, Bajulaye curated a couple of short stories which he paired with paintings. After showing these paintings and stories to his brother, actor Emmanuel Oluwaseyi Bajulaye, the idea to make a film was conceived. Almost immediately, he started working on a script that weaves the memories of loss, love, longing, the death of the past and future and a search for understanding through spirituality. That idea birthed Èkún Omi, Bajulaye’s directorial debut short film, which premiered and screened online from 27 to 29 June 2025 at Diversity in Cannes—a prestigious platform that celebrates underrepresented voices in global cinema. Its selection underscores the film’s power as a compelling narrative that resonates across cultures.

BAJULAYE’S VISION FOR ÈKÚN OMI

A visually immersive and thought-provoking short, Èkún Omi explores migration, identity and memory from an intrinsically Yoruba lens. Drawing from the director’s decade of research and interest in Yoruba spirituality, ritual, cosmology and aesthetics, Èkún Omi, beyond grappling with migration and the indecision to migrate, is a cinematic representation of the Bajulaye’s cultural thoughts and interest. Set during the Nigerian Civil War, the film follows the dream-induced conversation of Agboogun (Andy Eqwuatu), Michael (James Anite) and Obadare (Femi Ogunjobi), an elder and custodian of Yoruba wisdom and culture. Tragedy has met Agboogun’s migration decision and when the film starts, we see him in a heavily theatrical gesture in conversation with these men and the trance-like image of his dead wife (Funmi Olagunju). Their conversation fittingly dances around migration, memory, love, loss, community and the cultural and historical importance of Ifa. In an alternate universe, we meet Lagbaja (Emmanuel Bajulaye) and Omotola (Treasure Obasi Johnson) lovingly having a difficult conversation about leaving or staying. Lagbaja’s mind is casted abroad while Omotola is quick to remind him of the importance of honouring one’s ancestral home. Though their conversation doesn’t settle on a conclusion, their dialogue reiterates the innate inabilities of their home country’s government officials to provide social, economic and political stability. It is this tension, uncertainty, emotional burden and trauma which migration enforces on the mind of migrants that Balujaye’s film firmly tackles.

shop the republic

BAJULAYE AND ÈKÚN OMI’S JOURNEY

Born and raised until age ten in Nigeria, Bajulaye migrated with his parents to the United Kingdom and has since lived outside the shore of the country. Thus, over the decades, he has had a gnawing longing to understand where he comes from as a way of connecting to who he is, his parents and ancestors. This cultural longing has shaped the stories Bajulaye tells, the images he paints and the kind of dance he leans into:

Through my work, I am trying to excavate that feeling of what it means to rekindle and fall in love with yourself not through a caricature or prying lens but one which understands culture as an informative and evolving aspect of humanity. I believe that knowledge of your culture and ancestry helps you stay grounded in who you are. My goal is to find a way to weave those proverbial, ancestral and deep meanings into something that is palpable for audiences my age and future generations.

Bajulaye’s decision to migrate is anchored on numerous reasons which are not limited to seeking something different and better livelihood. While he believes it is intrinsically normative to be hopeful and expectant after migrating, migrants’ realities do not often correlate with that hope and expectation. The resulting effect of this on African migrants is the subconscious and gradual depletion of their cultural confidence. Thus, in making Èkún Omi, Bajulaye wants us to go within and excavate neglected cultural curiosity and identity. He told me that, ‘Going within is the way to find that universal story. If I can know myself better, I am showing myself, parents and ancestors the best way to continually bring to life our culture and how universal it can connect with other people.’

As highlighted earlier, the cinematic foundation of Èkún Omi resides in the stories and picture collection he created years ago. This book, spanning almost a decade in development, features a series of evocative paintings and in-depth research on the themes of migration and its profound effects on Africans on the continent and in the diaspora. In honouring each of his artistic mediums—writing, painting and dancing—Èkún Omi is lushly filled with markers of the director’s African identity and Yoruba spirituality. With this film, Bajulaye is telling his kind of stories and propagating his ideas. African filmmakers of his generation often embrace their cultural roots and ancestry when making art-driven short films. But that often changes when they transition to making feature-length cinema projects. With the exception of some Malian and Senegalese filmmakers who propagate African imagery and visuals, many tend to move away from exploring their cultural aesthetics. Thus, having the complete creative freedom on Èkún Omi afforded Bajulaye the leisure to show what we need to see and remind us, and future generations, of our cultural strength and might. This sense of artistic responsibility is what will define his filmmaking practice.

shop the republic

AFRICAN CINEMA IMAGERY AND THE AESTHETICS OF ÈKÚN OMI

Bajulaye’s use of imagery in Èkún Omi is admirable. In keeping with the Yoruba and broader African visual aesthetics, the film adopts a realistic and dedicated style that tenderly captures the vibrancy of Yoruba colours and their symbolic meaning. Its sonic design evokes the poetic and metaphorical undertones of Yoruba’s onomatopoeic language. The costume design, art direction, production design and makeup embodies the distinctiveness Yoruba culture and identity. ‘For the costume, we wanted to make sure that we were able to aesthetically pay homage and inspiration from Yoruba and African imagery. I wanted to make the film in a way that people can be visually pleased with what they encounter onscreen,’ Bajulaye told me.

Dance, for the Yoruba people, is a spiritual practice. It isn’t just the wilful movement of limbs nor the coordinated forming of shapes. Depending on the setting, dance can act as a vital expression of cultural identity and spirituality that communicates spiritual narratives to initiated onlookers. Rooted in religious practices, dance is an homage-paying exercise to Orishas. With Èkún Omi, Bajulaye tried excavating the spiritual importance and essence of this limb-moving exercise to the Yoruba people: ‘Dance and performance are important to the Yoruba people and I wanted to represent that in a theatrical way that honoured the Yoruba way of expressing themselves in an entertaining way.’

Growing up, one quickly learns the value of preservation from a parent or elder siblings that hoards things. This gesture elongates the lifespan of certain things. It bestows a sense of immortality on an object. Judging that Èkún Omi speaks to the personal, cultural and historical importance of cultural preservation, it becomes important to ask the director about his thoughts. In response, Bajulaye reiterates the importance of valuing who we are and what we have achieved over the decades as a people. He believes that this sense of cultural awareness can make us conscious of our place in the world and more strategic in making cultural, social, economic and political decisions. As an artist and filmmaker, he sees it as his cultural and artistic responsibility to replicate and explore these cultural values in his work. In Bajulaye’s words:

The reason I go back to study the past and weave it into my artistic expression is because it provides me confidence and understanding that as a people, we have such rich history and culture and resources that are largely untapped. These resources tell of the infinities of our stories and the unending potential to be able to tap from them. Africans aren’t just the future; we are now. However, it is what we do and understand now that will make the future greater. The future doesn’t like me like pretenders. Thus, in my artistic practices I ensure that I immerse the value of our ancestry into it.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

shop the republic

PRESERVING AFRICAN CULTURE AS A POLITICAL ACT

My conversation with Bajulaye swerved to unpacking the preservation tendencies of Nigerians and Africans. As a people, do we have the insight to preserve our culture? Does the absence of governmental and cultural institutions have a role to play in the lukewarm attention given to preserving our culture? The director suggests that as a people we have an intrinsic cultural preservation culture. The difference lies in the intent and motivation. Are we preserving out of fear, survival instincts or out of cultural and historical importance?

There is cultural preservation out of inspiration and preservation because we recognize its cultural value. I think the government plays a part as there are no institutions that can preserve our culture. That intrinsic urge to keep things need to move from its fear factor or survival instincts to an active, culturally and future minded aspect of building the muscle and ability of taking care of our cultural artefacts and totems.

Bajulaye also mentions how colonialism shifted our artistic values and priorities. This shift made us acute consumers of western ideologies. This plays out in our educational and career choices. Often, these decisions are not made with consideration of individual passions and societal needs. Instead, there is a hyperfocus on flashy, ‘prestigious’ courses. In Bajulaye’s words:

We are not thinking of the balance of society which is that there need to be farmers, doctors, lawyers, artists and culture practitioners. Society can’t be balanced if these different spaces and jobs aren’t occupied. We need to get back to the harmony of understanding that culture is something that needs to be preserved and artistic expression is what preserves this. Art reminds us of who we are, have lost and have.

The colour grading and shooting style of Èkún Omi are influenced by Andrew Dosunmu’s Mother of George. Aesthetically, the film also draws from Bajulaye’s painting. Julie Dash’s Daughters of Dust further shapes its engagement with memory, the friction between the past and future and the tension of leaving one culture behind while entering another. Describing the visual language and aesthetics of African cinema, Bajulaye says it is steeped in memory and highly cerebral. Traditionally, Africans transmit stories orally through griots, town criers and older people who are custodians of knowledge and history. Bajulaye believes that African filmmakers need to find a way to piece all these elements together in their storytelling. As Africans, our storytelling style and sensibilities vary from that of other continents. This style and sensibility are informed by our daily realities and culture. For filmmakers hoping to tell authentic African stories, this implies the need to further understand culture and history which makes cinema beautiful.

In Èkún Omi, Bajulaye shows the brilliance and science of Ifa in addressing mental health challenges. Anchored on Obadare, the film shows that Yoruba spirituality (particularly Ifa) is grounded in a system and science that, for devoted learners, offers a pathway for understanding the self and the world. Through Obadare, the film also emphasizes the cultural importance of elders in Yoruba communities. As custodians of knowledge, they help preserve and transmit collective wisdom. In exceptional cases, their wisdom and depth offer not only modern solutions to mental health difficulties but also tools for cultural preservation with future and technological understandings. According to Bajulaye:

Obadare is used to anchor this as a reminder of the importance of knowing your root because it allows you an opportunity to overcome adversaries and difficulties. Even when people are going through mental difficulties, one of what a good therapist recommends is for you to go within and learn why things might be happening. Digging deep allows you to find answers.

As Èkún Omi continues its festival circuit tour, Bajulaye hopes to build a community of people who will carry the film’s message. People who will connect with its cultural value and use it as a means of deep self-understanding, leading to both an inward reflection and outward transformation. Bajulaye also plans to screen Èkún Omi in Nigeria and across Africa, and to make the film available on streaming platforms that, in his words, will ‘afford people the opportunity to watch the film and define what migration means to them and how they have been able to find themselves or locate themselves within their culture.’⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N2 Who Dey Fear Donald Trump? / Africa In The Era Of Multipolarity

₦40,000.00