Photo illustration by Dami Mojid / THE REPUBLIC. Photos provided by the Author.

THE MINISTRY OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS

The Fading Pride of Ikoyi Cemetery

Photo illustration by Dami Mojid / THE REPUBLIC. Photos provided by the Author.

THE MINISTRY OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS

The Fading Pride of Ikoyi Cemetery

Across cultures and histories, cemeteries have stood as more than places of burial—they are enduring markers of how societies understand memory, honour and identity. To bury the dead is not just to lay them to rest, but to inscribe their lives into the landscape of the living. The design, care and location of cemeteries reflect values about legacy, belonging and historical consciousness. They offer insight into who a community chooses to remember and how that remembrance shapes civic space. In cities like Lagos, where rapid urbanization constantly reorders space and memory, cemeteries serve as some of the last remaining anchors of historical continuity. They are archives in stone and earth; quiet but powerful spaces where personal and collective histories converge. When these spaces are neglected or erased, it is not only graves that are lost, but also the stories, struggles and aspirations they silently preserve.

Nowhere is this tension between memory and modernity more visible than in the cemeteries of Lagos, particularly Ajele and Ikoyi. Each of these spaces, in its own time, reflected the city’s evolving relationship with class, power and identity. Ajele Cemetery, nestled in the heart of colonial Lagos, was once a proud resting place for prominent African families, Afro-Brazilian returnees and Saro elites whose influence shaped early Nigerian society. As Lagos expanded and redefined its urban core, Ikoyi Cemetery emerged in the late 19th century as a new locus of remembrance—planned, orderly and symbolically tied to the city’s administrative and residential elite. Together, these cemeteries map the shifting geographies of prestige and memory in Lagos, revealing how burial grounds can mirror broader social transformations. But they also show, in the current state of neglect for Ikoyi, how vulnerable these histories are when cities no longer prioritize the act of preserving memory in the form of burial places.

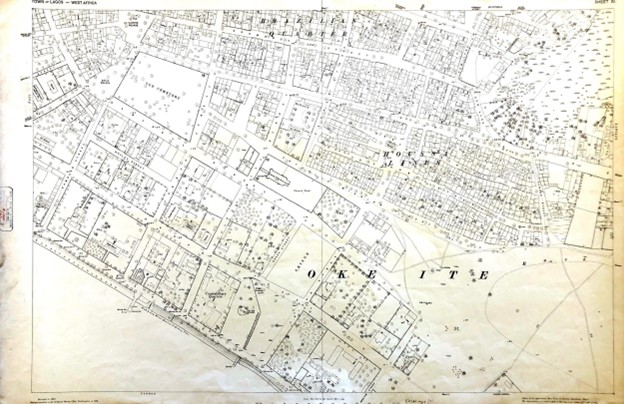

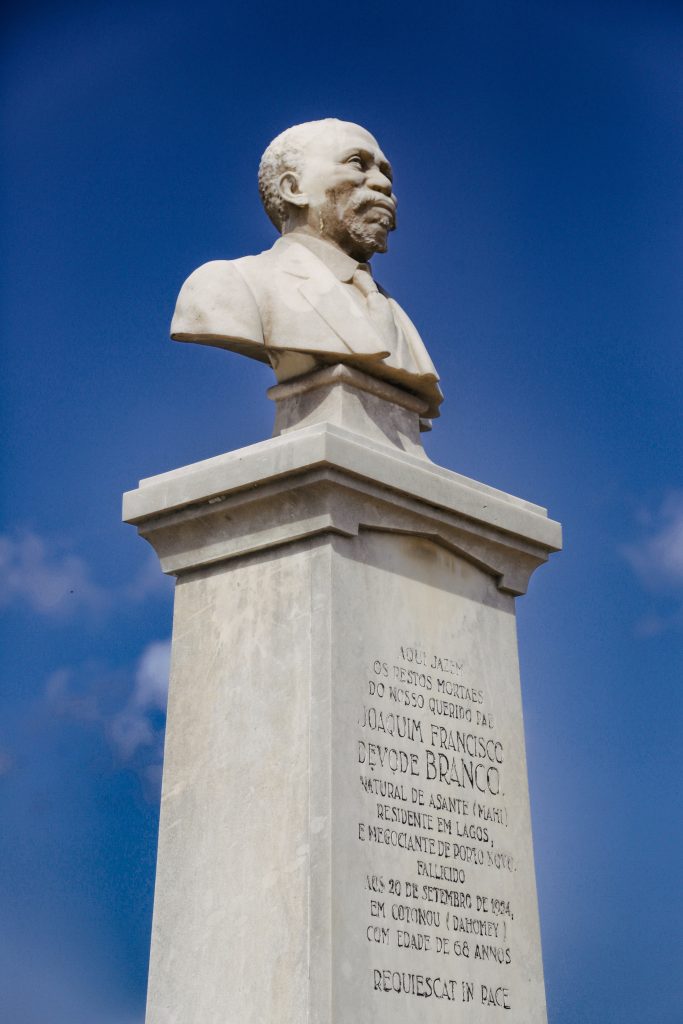

In the late 1870s, the bustling Crown Colony of Lagos found itself grappling with an age-old problem: space. The British colonial government recognized that the city’s sole public cemetery—the Ajele Street Cemetery, nestled in the heart of Popo Aguda, or the Brazilian Quarters—was becoming overcrowded. Tombstones were springing up like sentinels in the dense graveyard, each marking the resting place of Saros, Afro-Brazilians, West Indians, Europeans and locals alike. As the city grew, so did the number of interments and with them, the need for more space to honour the departed with dignity. The Ajele Cemetery had been a significant part of Lagos’s history, although its exact origins remained murky. Historic newspapers of the era, such as The Lagos Weekly Record, The Lagos Observer and The Eagle and Lagos Critic, frequently listed burial announcements for those buried within the cemetry’s grounds. Each grave told a story, often marked by elaborate tombstones crafted by skilled Afro-Brazilian or Saro masons, whose artistry turned these markers into monuments of remembrance. But as the years rolled on, the limits of Ajele Cemetery became glaringly apparent. The colonial authorities, spurred by necessity and the city’s relentless growth, sought a solution. The answer lay beyond the MacGregor Canal, in what is now the Obalende area, where a new cemetery would take shape on the easternmost edge of Lagos Island. By 1880, this New Cemetery was ready for public use. The Lagos Colony Government Blue Book of 1880/1881 proudly listed its development under the Public Works Department and The Lagos Observer heralded its availability in the first year of its publication. Strategically located, the New Cemetery stretched along Ikoyi Road, which, in those days, skirted the canal flowing into the Five Cowrie Creek. Its placement was not only practical—given the shortage of spacious land on Lagos Island—but also symbolic, marking a shift in the city’s urban planning. Today, with the ever-changing map of Lagos, its original bounds can still be traced: bordered by the Abdullahi Adamu Housing Estate to the north, Radio Nigeria to the east, Ikoyi Road to the south and the Eti-Osa Local Government office to the west. As the years passed and the cemetery expanded, it grew beyond its original boundaries. The addition of land across Ikoyi Road pushed its borders to Obalende Road in the south, Dodan Barracks in the east and nearby residential blocks to the west. This new burial ground became a place where generations of Lagosians—rich and poor, foreign and native—found their final rest, cementing its place as a cornerstone of the city’s ever-evolving history. The story of the New Cemetery was one of adaptation, resilience and reverence. Currently, it stands as a quiet witness to the passage of time, a bridge between eras and a reflection of Lagos’s journey from a colonial outpost to the vibrant metropolis it is today.

THE DEATH OF AJELE CEMETERY

The old cemetery on Ajele Street stands as a fading yet powerful monument to a Lagos that once centred its identity on a diverse and ambitious African elite. It symbolizes a time when the city’s heartbeat in the colonial core and its most revered spaces of memory were shaped by African agency, aspiration and cosmopolitanism. To be buried at Ajele was not merely a matter of death, but of social recognition; it reflected one’s status, contribution and connection to a wider transnational world of Saros, Afro-Brazilians, liberated Africans and local dignitaries. The careful selection of those interred—linguists, merchants, educationists and community leaders—reveals an implicit process of social valuation, a silent agreement about whose lives were worthy of permanence in the urban fabric. Their tombstones speak to Lagos’s character as a nineteenth-century cosmopolitan port city, where cultural hybridity, class ambition and African modernity coexisted with colonial imposition.

In its quiet decay today, now repurposed as the Campos Memorial Mini Stadium, Ajele tells a sobering story about how urban memory is erased or displaced in tandem with shifts in power, space and historical priority. In December 1971, a sombre chapter unfolded in Lagos’ long and layered history. Brigadier Mobolaji Johnson, the then military governor of Lagos State, issued (Ajele Cemetery Case) a controversial directive: the Old Cemetery—an age-old burial ground that had served the city for over a century—was to be cleared to make way for the construction of the Lagos State Secretariat.

The news, though communicated swiftly, stirred deep discomfort among residents and historians alike. The ground held the remains of generations past, including revered figures whose legacies shaped the fabric of Nigerian society. Yet, despite public unease, the exhumations proceeded. Among those disturbed was the grave of Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther, the first African Anglican bishop, the revered linguist and the first African Anglican bishop and a symbol of resilience and reform alongside his mother, Hannah Crowther, who passed on October 13, 1883, a woman whose legacy lived through her son’s monumental achievements. His remains were reverently relocated and reburied within the grounds of the Cathedral Church of Christ, Marina. But not all found a new resting place. Some bodies vanished amidst the process, lost to time and neglect.

shop the republic

THE BIRTH OF IKOYI PRISON

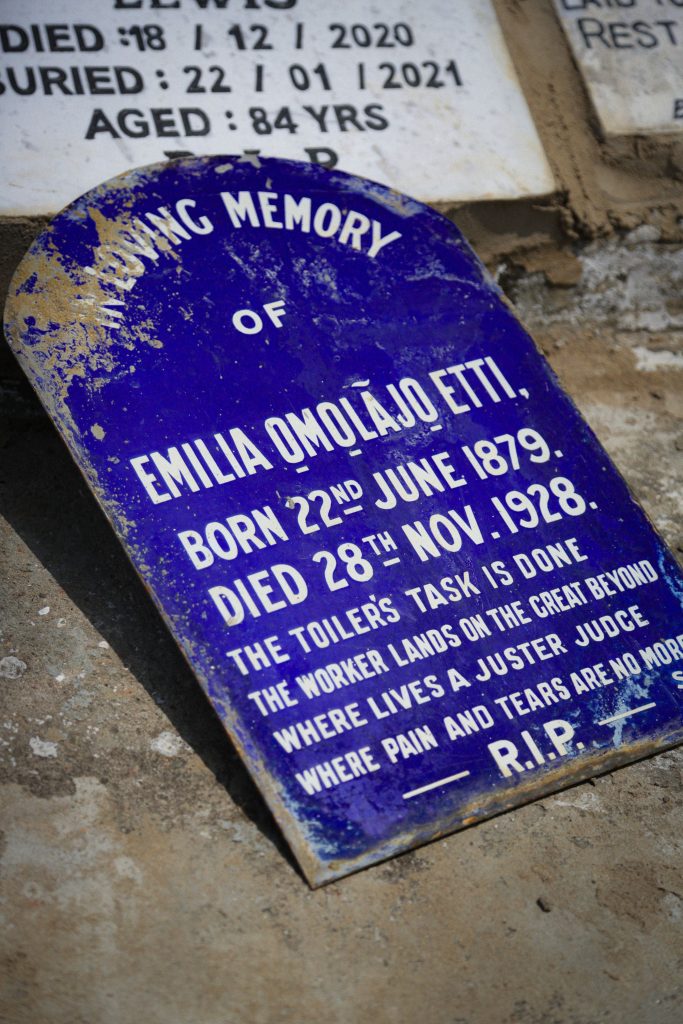

Ikoyi Cemetery is more than a final resting place. Unlike Ajele Cemetery, which once stood at the heart of colonial Lagos but gradually fell into a bastardization by the exhuming of bodies and bones and its planned but failed replacement as the secretariat of the Lagos State Government during the military regime in the 1970s, Ikoyi rose in prominence alongside the expansion of elite residential and administrative zones and most especially the need to have adequate spaces for burials. Where Ajele came to symbolize erasure and the faded memory of early colonial figures, Ikoyi became a space of curated remembrance, reserved for those whose lives embodied prestige, influence and cultural legacy. Though the identity of its first interment remains unknown, the cemetery quickly became a site of selective memory—a landscaped archive of Lagos’s history. It reflects not just who is remembered, but where memory itself is allowed to endure in a city always renegotiating its past. Among these names is Ada Adela Holm, who died on August 10, 1892. The beloved wife of Neils Walwin Holm, a celebrated photographer of his time, Ada’s life was intricately tied to the burgeoning arts and culture of Lagos. Another grave holds Christiana Josepha Carrena, who died on September 19, 1903, a matriarch whose son, Albert B. Carrena, became a revered civil servant. Even foreign dignitaries found their way to Ikoyi; Herr Carl Wilhelm Johanning, the German agent of Witt and Busch, was interred here after his death on December 19, 1896, Giuseppe del Grande, the Italian consul and agent of Messrs. Cyprian Fabre & Co. and Susan Laura Carter, the wife of Sir Gilbert Thomas Carter, governor of Lagos Colony (1891-1897).

Ikoyi Cemetery encapsulates the transformation of Lagos from a colonial stronghold into a postcolonial metropolis, mapping in stone and soil the reconfiguration of power, prestige and memory. As Lagos grew outward from its colonial core, the city’s political and social elite followed, establishing new centres of authority in Ikoyi. The cemetery rose in tandem with this shift, gradually replacing Ajele, which once lay at the symbolic heart of colonial Lagos, as the burial ground of choice for those whose lives signified influence, accomplishment or status. In this way, Ikoyi became a curated space of remembrance, its gravestones marking not just individual lives, but a broader reordering of urban memory. The interment of figures such as Ada Adela Holm, linked to the city’s artistic heritage and Christiana Josepha Carrena, mother of a prominent civil servant, reflects the cemetery’s alignment with narratives of legacy and civic contribution. Even foreign dignitaries such as Herr Carl Wilhelm Johanning, Giuseppe del Grande and Susan Laura Carter were absorbed into this landscape of prestige, further reinforcing Ikoyi’s role as a selective archive of Lagos’s cosmopolitan elite. But Ikoyi does more than commemorate; it reveals the politics of who gets to be remembered and where. In its carefully chosen burials, architectural symbolism and historical continuity, the cemetery stands as a negotiated space where memory is not simply preserved, but shaped—where Lagos’s past is filtered through the lens of aspiration, visibility and spatial hierarchy. In contrast to Ajele’s decline into obscurity, Ikoyi’s endurance shows how remembrance in Lagos is uneven, always subject to the shifting tides of urban development, institutional care and social value.

shop the republic

THE SLOW DEATH OF IKOYI CEMETERY

Over the decades since its establishment, Ikoyi Cemetery has stood as a silent witness to the growth of Lagos, its population rising with the city’s relentless expansion. But what was once a revered resting place for some of the most notable figures in Nigerian history is now a shadow of its former self. The cemetery, steeped in history and architectural beauty featuring Gothic-like tombstones or tombstones with angelic figures and cherubim in marble, burnt bricks, stone, etc., is facing a slow decline—a victim of neglect and the pressures of a burgeoning city. In its early years, Ikoyi Cemetery was a place of order and reverence, its grounds carefully planned to accommodate the dead while honouring their legacies. But as the decades passed, the rising tide of Lagos’s population brought with it an overwhelming demand for burial spaces. Graves were placed without foresight; old tombs were paved over to make room for new ones and the once-orderly sections gave way to a chaotic cluster of headstones. Walkways disappeared, leaving visitors to navigate a maze of graves that tell stories of lives lived and histories lost.

Cemeteries like Ikoyi and Ajele are not merely burial grounds; they are historical texts—repositories of memory that trace Lagos’s transformation from a colonial port city to a sprawling postcolonial metropolis. These spaces matter because they reflect how a society chooses to remember and just as importantly, who it chooses to forget. In their prime, both cemeteries were deeply respected—Ajele representing an older cosmopolitan Lagos shaped by Afro-Brazilian, Saro and Creole elites and Ikoyi emerging as a curated site of prestige tied to the city’s expanding administrative and residential elite. Their layouts, materials and inscriptions—marble cherubim, gothic tombstones, angelic motifs—were deliberate acts of memory-making, projecting values of piety, class and legacy.

For decades, these cemeteries were tended as sacred civic spaces, where visitors came to mourn, reflect and connect with Lagos’s past. Ikoyi Cemetery, in particular, was orderly and well-maintained, a landscaped archive that reflected the dignity of those interred. Ajele, nestled in the colonial heart of Lagos, held generations of distinguished African families whose names once shaped education, commerce and governance.

Today, however, Ikoyi faces a slow and painful erasure. Urban pressures and population growth have turned Ikoyi into a cluttered sprawl where graves are layered without care and older tombs are paved over or lost beneath newer ones. Walkways have vanished and the spatial logic of remembrance has collapsed into chaos. Ajele suffered even more, now repurposed as the Campos Memorial Mini Stadium after decades of lying empty in ruins and sidelined in public memory. Their neglect is not just a logistical issue; it signals a broader societal shift in how history, death and civic responsibility are valued. Preserving Ikoyi Cemetery means preserving Lagos’s layered identity—its cosmopolitan roots, its histories of African agency under colonial rule and the urban narratives of aspiration, migration and memory. To let them fall into disrepair is to allow those narratives to be buried once again, this time not by earth, but by indifference. In a city constantly reinventing itself, these burial grounds offer a rare stillness—a place where Lagos’s past and present meet and where its future might still learn to remember.

Speaking with architectural designer, Ọlọ́runfẹ́mi Adéwuyì, on the subject, he believes that our lack of maintenance culture, rooted in extractive traditions and a disregard for multifunctional spaces, undermines the potential of burial sites to serve as vibrant urban spaces that honour memory while fostering sustainability. He said:

The neglect of burial spaces stems from a broader lack of maintenance culture and a failure to treat such places with dignity. With limited resources, single-use spaces are unsustainable. Instead, cemeteries should be reimagined to serve multiple functions, like parks or memorial spaces, to ensure their relevance, upkeep, and long-term survival.

I think the root of the problem is that we don’t have a philosophy or psychology of care. From my perspective, our relationship with land and space in Africa has often been extractive rather than nurturing. I’m not sure we’ve ever really developed African landscaping traditions that reflect care rather than just taking, whether it’s for food, herbs, or other resources. To me, this speaks to a deeper cultural issue, one that’s been ingrained for a long time and that we need to consciously evolve beyond.

Another perspective is that people often lack awareness of the site’s significance—its stories, histories, and those buried there. The issue is that we treat it as distant history rather than living memory. If we reframe it as memory—something people can connect with—it could become an urban open-air museum, blending remembrance with multiple uses and deeper public engagement.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

shop the republic

Ikoyi Cemetery is not just a resting place. It is a repository of Nigeria’s history, a bridge to the past and a reminder of the lives that shaped the Lagos we know today. Without action, it risks slipping into oblivion, taking with it the stories of generations. There is the risk of this piece of history crumbling before our eyes. Instead, let us honour it as the monument it was always meant to be⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N2 Who Dey Fear Donald Trump? / Africa In The Era Of Multipolarity

₦40,000.00