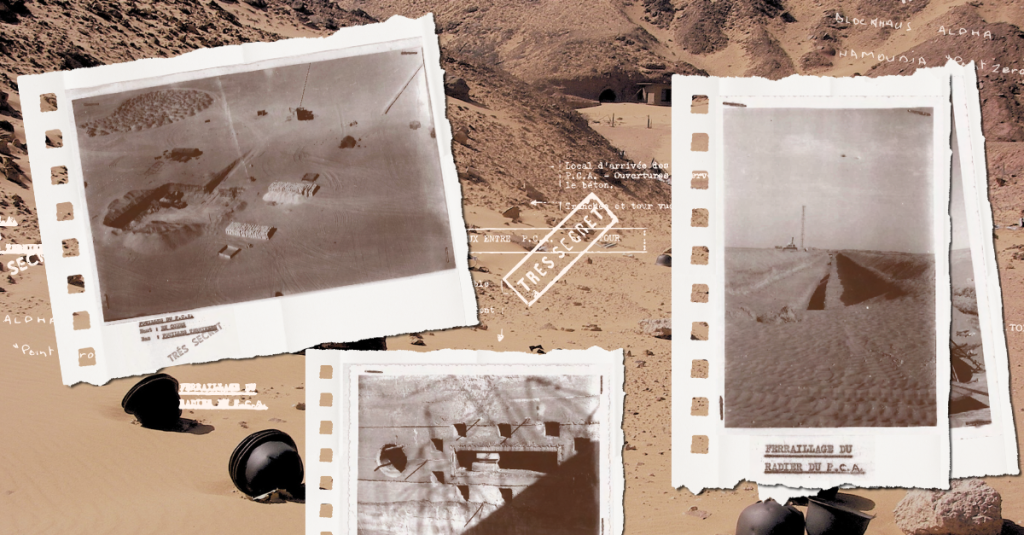

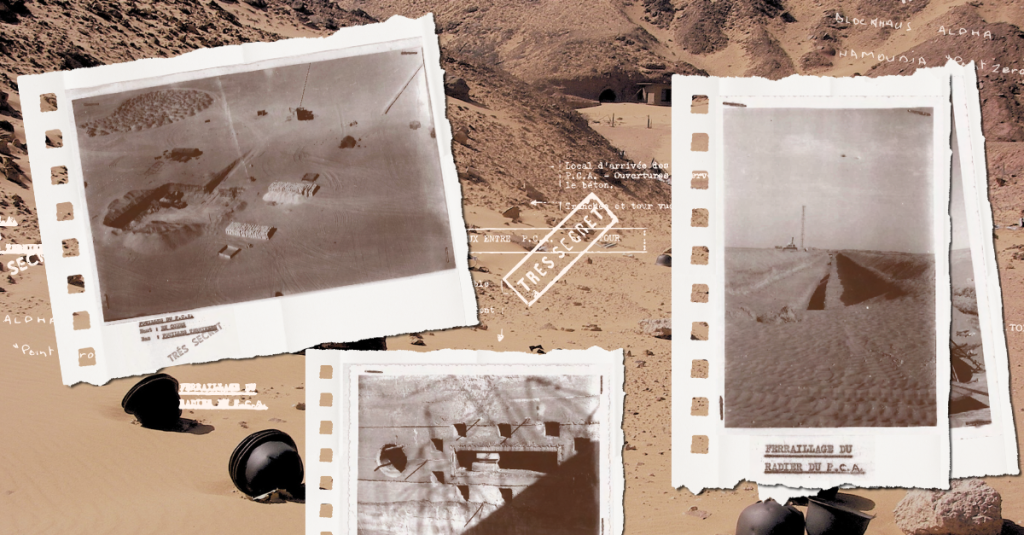

Photo Illustration by Ezinne Osueke / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref: Photography by Bruno Barrillot of France’s nuclear sites in Reggane and Ecker in the Algerian Sahara / OBSERVATOIRE DES ARMEMENTS.

THE MINISTRY OF WORLD AFFAIRS

How France Secretly Poisoned the Algerian Sahara

Photo Illustration by Ezinne Osueke / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref: Photography by Bruno Barrillot of France’s nuclear sites in Reggane and Ecker in the Algerian Sahara / OBSERVATOIRE DES ARMEMENTS.

THE MINISTRY OF WORLD AFFAIRS

How France Secretly Poisoned the Algerian Sahara

On 13 February 1960, the French colonial and military authorities detonated the first of 17 atomic bombs in the Algerian Sahara. The site of the inaugural nuclear bomb was Reggane—a district with a town, villages and an oasis—located in the Tanezrouft Plain of the colonized desert, approximately 1,000 kilometres south of Algiers. France had thus entered an exclusive nuclear weapons club, becoming the fourth country in the world to possess arms of mass destruction, after the United States of America, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the United Kingdom. This exclusivity was seemingly unaffected by the destruction of human, animal and vegetal lives, nor by the toxification of the hundreds of thousands of kilometres of natural, living and built environments that these bombs caused over the following decades in Algeria and elsewhere.

Between February 1960 (about five years after the outbreak of the Algerian Revolution and four years after the first exploitation of Algerian oil) and February 1966 (around four years after Algeria’s independence from French colonial rule), the colonial and military authorities exploded four atmospheric and 13 underground nuclear bombs in the Algerian Sahara. They also conducted tests of other nuclear technologies and weapons there, spreading radioactive fallout and causing irreversible contamination across Algeria, Central and West Africa, and the Mediterranean (including southern Europe).

This year marks 65 years since the detonation of France’s first bomb in the Sahara and 80 years since the United States dropped atomic bombs in Japan’s Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively, within which Congolese-sourced uranium was critical. But up until this day, the significance of North, West and Central Africa in global nuclear politics is often overlooked—and the facts and deeds of France’s nuclear weapons programme in the Algerian Sahara remain a military secret. Most French institutional archives that document the production, detonation and consequences of these weapons of mass destruction are classified and inaccessible to the public. This imposed amnesia not only encumbers the writing of France’s atomic histories in the Algerian Sahara, but also prevents victims, veterans and civil groups from claiming the socio-economic, psychological, spatial and health compensations and recognitions that should be accorded to them according to protocols of international law.

NAMING THE ATOMIC BOMBS

The four atmospheric bombs were named Gerboise Bleue, Blanche, Rouge and Verte (Blue, White, Red, and Green Jerboas) after a small jumping desert rodent and were detonated in Reggane (also written as Reggan) between February 1960 and April 1961. For their part, the underground bombs were named after gemstones: Agathe (Agate), Béryl (Beryl), Émeraude (Emerald), Améthyste (Amethyst), Rubis (Ruby), Opale (Opal), Topaze (Topaz), Turquoise, Saphir (Sapphire), Jade, Corindon (Corundum), Tourmaline (Tourmaline) and Grenat (Garnet). They were detonated at In Ekker (also spelt In Ecker or In Eker), on the Hoggar mountain of Taourirt Tan Afella in the Algerian Sahara, approximately 600 kilometres south-east of Reggane, between November 1961 and February 1966.

These atomic detonations were conducted despite the approval of Algeria’s referendum on self-determination by 75 per cent of voters on 8 January 1961, and Algeria’s ensuing independence from France in March 1962 after 132 years of French colonial rule, which began in 1830. Signed between the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic and the French Fifth Republic and presided over by General Charles de Gaulle in Évian-les-Bains, on 18 March 1962, the ceasefire and peace treaty—known as the Evian Accords—formalized the independent status and conditions of Algeria and institutionalized the forced ‘cooperation’ between the two countries (the colonizing power and formerly colonized entity). Among other numerous colonial continuations, the Evian Accords allowed the French army to continue using its nuclear sites in the Sahara after Algeria’s independence for five years.

shop the republic

BUILDING THE ATOMIC CENTRES

To carry out its secret nuclear weapons programme in the Algerian Sahara, the French colonial regime built two military bases: the Centre Saharien d’ Expérimentations Militaires (CSEM) or Saharan Centre for Military Experiments in Reggane, and the Centre d’ Expérimentations Militaires des Oasis (CEMO) or Oasis Military Testing Centre in In Ekker. An estimated 20,000 people (civilian and military) worked or served in the Saharan nuclear bases between 1960 and 1966. It is unclear whether the Saharan people who worked on the construction of CSEM, CEMO or the firing tunnels are included in this estimation. However, the French colonial regime estimated that a sedentary population of 40,000 lived in the area where the atmospheric bombs were detonated, mainly the Oases and the Touat Valley, north of Reggane. In this estimate, there is no mention of the nomadic and semi-nomadic populations of Algeria and other parts of the Sahara. The construction of CSEM and CEMO and France’s nuclear weapons programme had devastating effects on the construction workers, as well as on the Saharan people, who continue to live on their land and suffer contamination by radioactive materials.

The workforce responsible for constructing the buildings and infrastructure of France’s first atmospheric nuclear detonations in the Sahara included Algerian populations. According to Charles Ailleret, leader of the Commandement Interarmées des Armes Spéciales (Special Weapons Joint Command)—in L’Aventure Atomique Française, the entity responsible for the realization of the built environments for the bombs, ‘one cannot speak of the construction works carried out on the base and the firing field without mentioning a category of labour, which was both a very effective means of the construction of the installations and an essential element of the legends of the operations.’ This category was named the Population Laborieuse du Bas-Touat (PLBT) or Working Population of Southern Tuat. The Tuat region borders Reggane. It contains a series of oases, which extend over 160 kilometres, from the district of Bouda in the North to Reggan in the South.

The exact number of these workers is unknown. Referring to their assigned appellation and the financial aspects of the labour force, Ailleret stipulated that ‘the considerable accounts that the employment of thousands of workers justified were henceforth drawn up using the “PLBT”, a term which meant indigenous Saharan hired by the centre.’ These thousands of workers were indispensable to the realization of France’s secret construction works in the Sahara. Ailleret stated that when French officers requested an additional labour force to execute the works, they demanded more ‘PLBT’, adding that, towards the end, no one knew what this abbreviation stood for.

shop the republic

SAHARAN CONSTRUCTION WORKERS

The Algerian workers from the Tuat region were employed in various kinds of construction work, especially where French engineers’ construction machines, brought to the Sahara, could not be used due to their inadaptability to the Sahara’s soil. In Christine Chanton’s Veterans of French Nuclear Tests in the Sahara, an unnamed French officer who led construction work on a building site said that Tuat workers ‘were employed for handling the construction sites and as far as I was concerned, they loaded and unloaded the trucks with the construction materials.’ Another unnamed French officer claimed that they were contracted to build the main paved road between Reggane Plateau and Hamoudia, reporting that ‘the construction works were conducted by night for approximately one month with the participation of a hundred PLBTs.’

With the expansion of building sites and the increasing number of construction activities, the so-called ‘PLBT’ workers were insufficient and additional personnel were necessary, prompting French colonial administrators to look to other regions of the Sahara in Algeria and elsewhere. The appellations for these newly hired African Saharan workers changed, reflecting, as with the Tuat region, the area from which the workers came, including the Population Laborieuse du Tchad (or Working Population of Chad), Population Laborieuse du Djebel (or the Working Population of Djebel), and Population Laborieuse des Oasis (or Working Population from the Oases). The workers lived in self-built shelters near the construction sites. Like French personnel working in CSEM and CEMO, they were exposed to radiation. None of the Saharan workers received any medical follow-up after their participation in the construction jobs.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

shop the republic

CONTAMINATING AND KILLING LIVES

In June 1992, 32 years after the detonation of France’s first atmospheric nuclear bomb in the Sahara, the French environmental activist and member of European Parliament representing the French Green Party, Solange Fernex (1934–2006), interviewed various Saharan workers who had been employed in Reggane and In Ekker, as well as Algerian nuclear survivors. The interviews were conducted to raise awareness of the ongoing consequences of French nuclear weapons in the Sahara. The testimonies covered various topics, including the working conditions, contract terms, lack of protection during and after the detonation of the nuclear bombs, lack of information about the impact of atomic weapons, diseases and symptoms they suffer from, memories of the explosions, dangers they faced after the explosions, the invisibility of radioactivity, lack of trust in the French and Algerian authorities, arable lands that had become unproductive, widespread infertility in the region, lack of medical follow-up, living with fear and death.

In a year of nuclear-related strife, with Algeria recently vigorously condemning Israeli aggression toward Iran in the United Nations Security Council while handing over non-permanent membership to the DRC in the commemoration year of Hiroshima and the Ninth Tokyo International Conference on African Development, it is worth reflecting on the wider (deadly) politics of nuclear weapons programmes. In the Saharan case, the resulting architecture and ruins that are still occupying regional landscapes and African atmospheres continue to contaminate, if not kill, human and nonhuman lives. The thousands of Saharan people who built the facilities that produced the irreversible and permanent toxification of their own bodies, lands, crops, waters and air without their knowledge and consent continue to suffer from the humanitarian and environmental disasters of radioactivity. The permanence of French colonial toxicity in the Sahara is occupying and damaging the realities and imaginaries of present and future generations in Africa and elsewhere⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N2 Who Dey Fear Donald Trump? / Africa In The Era Of Multipolarity

₦40,000.00