Photo Illustration by Ezinne Osueke / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref: Red Palm Oil Production / SAFARI TOURS.

THE MINISTRY OF BUSINESS X THE ECONOMY

Nigeria Was Once the World’s Largest Palm Oil Producer—What Happened?

Photo Illustration by Ezinne Osueke / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref: Red Palm Oil Production / SAFARI TOURS.

THE MINISTRY OF BUSINESS X THE ECONOMY

Nigeria Was Once the World’s Largest Palm Oil Producer—What Happened?

From the 1950s to the 1970s, Nigeria was the world’s largest producer and exporter of palm oil. It produced more than enough to meet domestic demand and accounted for 40 per cent of the global palm oil market. This was a period when agriculture powered the economy and was Nigeria’s main export. Alongside palm oil, Nigeria produced groundnuts, cocoa, cassava, and other crops in impressive volumes. During this golden era, Nigeria accounted for over 40 per cent of the global palm oil market, comfortably dominating international trade in the commodity. But today, that dominance has vanished. Nigeria’s share of global palm oil production has plummeted from over 40 per cent in the 1970s to less than two per cent in 2024, according to data from the United States Department of Agriculture.

In 2024, the president of the National Palm Produce Association of Nigeria, Alphonsus Inyang, revealed that Nigeria spends $600 million annually on palm oil importation. Foreign Trade Reports from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) show that crude palm oil (CPO) and palm oil fractions consistently top Nigeria’s agricultural imports, with import values exceeding ₦100 billion every year.

PAST GLORY: HOW NIGERIA EMERGED AS A GLOBAL LEADER IN PALM OIL

Nigeria’s rise in the 1960s as the world’s leading palm oil producer was both a blessing of nature and a product of colonial agricultural policy. The country’s tropical climate supported the natural growth of oil palm trees, scientifically known as Elaeis guineensis, across the country’s southern region, providing food and income to farmers in rural communities. Much of the palm oil produced during the twentieth century came from wild groves, not cultivated plantations.

Dr Celestine Ikuenobe, the executive director of the Nigerian Institute for Oil Palm Research (NIFOR), explained this at a conference. He revealed that the colonial government, in order to maximize yields from these wild groves, established NIFOR in 1939 as an oil palm research station under the Department of Agriculture. While Nigeria served as the major centre, in 1951, the station’s scope was expanded to other British West African colonies, leading to the establishment of the West African Institute for Oil Palm Research (WAIFOR).

By the 1960s, Nigeria had become a global leader in palm oil production. Not only that, it had the richest collection of oil palm germplasm, and many countries visited the newly born West African giant.

THE DECLINE

Then came the oil boom. The fossil fuel was famously described by former Venezuela’s oil minister Juan Pablo Alfonzo as ‘the devil’s excreta’. Crude oil was discovered in the Niger Delta region in 1958, and international oil giant, Shell Plc secured a license to start drilling in earnest. By the mid-1970s, barely 15 years after the discovery, production tripled even more from around 5,000 to over two million barrels per day. This boom brought unprecedented wealth to Nigeria, making it the richest country in Africa and one of the richest in the world. Its revenue soared by over 50 per cent to an all-time high of ₦5.3 billion in 1976.

The government promised massive infrastructure development and electrification. It promised a better life for the citizenry, but what followed were decades of unchecked corruption and financial mismanagement. The oil boom shifted the government’s focus from other sectors. The excitement and economic prosperity were short-lived.

With the government’s focus shifted to crude oil, agriculture was abandoned, and palm oil production declined sharply. Ageing oil palm trees were not replaced, smallholder farmers were neglected, and research and policies inherited from the colonial government faded. The palm oil industry entered a prolonged downturn.

shop the republic

THE ROLE OF THE NIGERIAN CIVIL WAR

Experts like those at the Food and Agriculture Organization believed that the Nigerian civil war (1967–1970) also played a role in the decline of the country’s palm oil industry. It should be noted that Nigeria’s palm oil industry was centred in the tropical southern region, particularly the South–South and the South East regions. Researchers say that in the late 1960s into the early months of 1970, which marked the peak of the civil war, many palm oil plantations in the South East and South–South regions were either destroyed or abandoned.

After the civil war, most of the oil palm plantations were not revamped, nor were new trees planted. The impact of the civil war, combined with the newly found wealth in crude oil, sealed the fate of the palm oil industry by the end of the 1970s.

INDONESIA AND MALAYSIA TAKE OVER

Today, Indonesia and Malaysia dominate the global palm oil market, producing more than 80 per cent of the world’s supply. In 2024, Indonesia alone produced 46 million metric tonnes (59 per cent of global output), followed by Malaysia with 18.7 million MT (24 per cent). Nigeria, now ranked fifth, produced just 1.5 million metric tonnes, which is a meagre 2 per cent of global production.

When Nigeria was leading the chart in the 1960s–70s, these southeast Asian countries—Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand—had either not started commercial production of palm oil or were far behind in output.

NBS data shows that Nigeria imports from these countries and from Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire—two African countries that produce less than Nigeria. It is often claimed that Malaysia came to Nigeria to collect oil palm seeds and kick-start its own industry. While this has been exposed as a myth, experts clarify that what Malaysia actually did was leverage Nigeria’s early research and diverse oil palm gene pool. According to Dr. Ikuenobe, while Nigeria had extensive oil palm germplasm, Malaysia and Indonesia lacked genetic diversity. They visited Nigeria for oil palm genetic resources and the exchange of planting materials.

While Nigeria continued to rely on traditional wild groves and smallholder farmers, the southeast Asian countries industrialized palm oil operations, offering capital and incentives to farmers to scale up. In Nigeria, oil palm farmers were starved of credit and support.

shop the republic

NIGERIAN FARMERS HUSTLE MALAYSIA’S ‘SUPERGENE’

Today, many Nigerian smallholder farmers have turned to Malaysia’s genetically superior, high-yielding oil palm variety known as the ‘Malaysian supergene’ to improve productivity. They say the Malaysian variety grows faster and produces more oil palm fruits than Nigeria’s native variety, known as ‘Terena’. ‘Most of the seeds we use are imported from Malaysia. That’s the Malaysian supergene,’ says Victor Bassey, owner of Tripoli Oil Ltd in Benin City. Describing the Malaysian supergene, he said it is dwarf when grown but breeds faster and produces more yields than the Terena.

Bassey has about twelve employees in his palm oil enterprise, which comprises a refining mill and a nursery farm. He called for improved investment in both farming and industrialization in the palm oil industry to boost domestic production in Nigeria. He said climate change often affects palm oil planting, especially at the nursery stage. Speaking on refining, Bassey lamented over the fluctuating price of CPO, which is processed and refined into edible palm oil. He said:

One of the challenges we face here is the climate. Then, another challenge is the price of CPO. The price hasn’t been stable for a while. We buy CPO locally but factors like the price of transportation affect us. To find vehicle; sometimes even the food we provide for the workers have become expensive. Nobody wants to run a business that will make a loss.

The other farmers I spoke with cited more challenges, such as poor government support, limited access to land, and inadequate capital.

EFFORTS TO REVIVE NIGERIA’S PALM OIL INDUSTRY

Palm oil production in Nigeria dropped to 1.12 million metric tonnes in 2018, prompting national concern. In 2019, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) launched the Oil Palm Development Initiative to reverse the trend and reduce dependence on imports.

The CBN confirmed that Nigeria was spending millions of dollars annually on the importation of palm oil, putting more pressure on and depleting foreign exchange reserves. The initiative targeted the establishment of 100,000 hectares of plantations in the short term and 500,000 hectares in the long term. Stakeholders across the value chain, including smallholders, commercial farmers, and processors, were offered low-interest, long-term loans. In addition, the CBN restricted access to foreign exchange for palm oil imports.

The apex bank reportedly partnered with eleven states in the South–South and South East regions for the implementation of the project. The states supported with the donation of hectares of land for cultivation, while private sector investors like Presco Plc, Okitipupa Oil Palm Ltd, and Okomu Oil Palm Plc, were also involved. The goal was to significantly increase palm oil production in Nigeria in three to five years.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

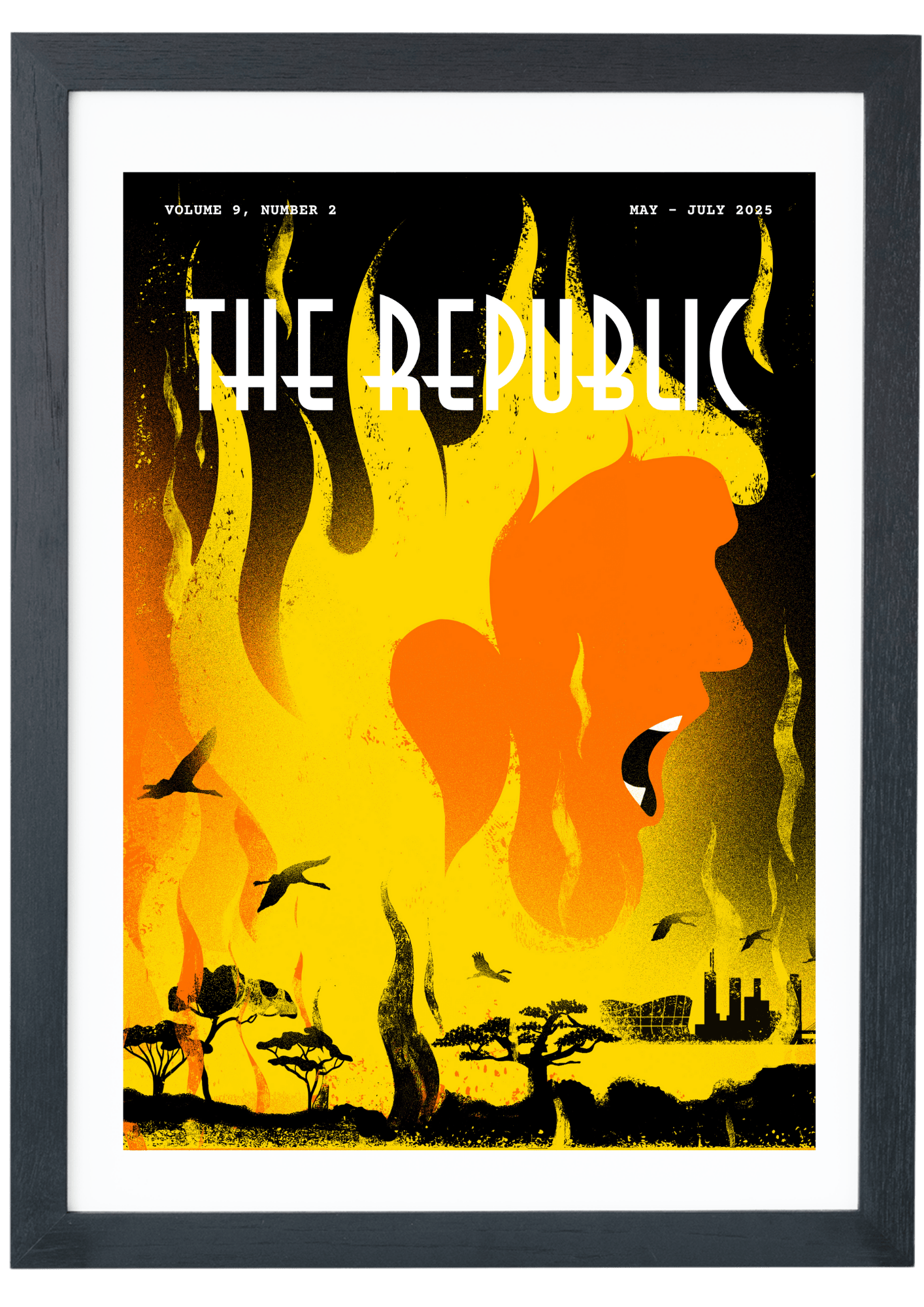

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

AGING AND DECLINING PLANTATIONS

Banjoko also noted that many of Nigeria’s oil palm plantations were established 30 to 40 years ago and are now beyond their peak productivity. He disclosed that major producers like Okomu Oil and Okitipupa have started replanting, but this process takes three to four years before new trees start yielding fruit.

Earlier this year, the largest shareholder in Okitipupa Oil Palm Plc, Pink Nominee Ltd, announced the acquisition of four new palm oil processing mills to be installed at the Ikoya, Apoi, Ilutitun and Iyansan Plantation estates in Ondo State. The company also announced that it had begun planting 750,000 to 1.2 million oil palm seedlings to boost production. Banjoko stated that the new plantations of the leading palm oil companies should begin to yield results in the next three years at least. He said:

We also have a lot of new players coming into the system, which is also very good. And of course, we are also not leaving behind the smallholder farmers playing in that space. But I think one of the reasons why we are also not getting there yet is that some of our plantations are old. Some of the plantations that we launched 30 years ago, and 40 years ago, are old, and the production level has declined. Like Okomu now is trying to replant, for example, I mean replacing the old ones. So that might take around three to four years. So, we should expect the increase, but because some plantations are old, they have outgrown their life cycle. We also have to prioritize replanting or replacing some of those oil palm plantations that gave us those numbers in the past.

SUPPLY CHAIN ISSUES

Banjoko, who is also the managing director of B.O. Farms Ltd, also noted that despite having bid-processing factories, Nigeria lacks sufficient raw materials to keep them running at full capacity. He said some factories have shut down due to a lack of oil palm fruit supply.

According to Banjoko, smallholder farmers often prefer to process palm oil using traditional crude methods instead of selling it to factories. This reduces the supply available for industrial processing and contributes to inefficiencies. He said:

We cannot focus on industrialization because, without raw materials, there is nothing called industrialization. Currently we have some factories that are not able to operate because there is no product. As I speak to you, even as of today, I have about three to four that lack of product is holding down. We have established factories, but there is no product. So, we cannot downplay cultivation.

Speaking on why smallholder farmers are reluctant to sell to processing factories, Banjoko said the compensation is likely poor, and they could get more value from refining themselves. ‘So, if I am able to process whatever I am getting from my five acres, three acres, I am likely to get more value,’ he said, ‘Then because of the other by-products, they also get seeds and other things. They would rather want to make the best of their product, just like it’s done in other value chains—cassava, maize.’

REFINING THROUGH TRADITIONAL METHODS

Mrs Grace Osofunke, an oil palm farmer and processor in the Ijebu axis of Ogun State, said it is more profitable to refine using traditional methods than to sell her harvests to factories. ‘Selling my palm fruits to the big factories doesn’t favour me. By the time I pay for labour, transport, and other costs, what they offer barely covers my expenses. At least I can control the quality and sell at a better price in the local market.’

Mr Godwin Bright, a former researcher at NIFOR and agricultural consultant, noted that smallholder farmers prefer to refine crudely to avoid being cheated. However, they are not able to fully extract all the products from the oil palm fruits. He said:

Smallholder farmers cannot fully maximize the value of the oil palm. From the oil palm, you can extract what they call kennel oil. You can extract the shafts. You can extract the shell. After the CPO. Even the oil itself can be turned into groundnut oil and other things. They don’t have the equipment to fully extract all these things.

With Nigeria relying on importation for about 50 per cent of its palm oil demands, the chief economist at SPM Professionals, Paul Alaje, warns that this situation further weakens the Naira and discourages local farmers. In our conversation, he noted that manufacturers who use crude palm oil for products may turn to importation if they cannot get the necessary quality and quantity locally. ‘The data indicate that we are dealing with sufficiency or quality-related issues,’ Alaje explains, ‘Manufacturers may have no choice but to import if they cannot get the required quantity or quality locally. This puts pressure on the local currency, discourages local farmers, and threatens employment in the agricultural sector, or that sub-sector as it affects palm oil in Nigeria.’

He urged the government to develop plans to encourage investment in the palm oil industry while ‘the private sector, especially those in agro-business, should also see this as an opportunity, as demand for palm produce has increased.’

REVERSING THE TREND

To reverse Nigeria’s dependency on palm oil importation, Banjoko and Alaje advocate aggressive replanting, stronger financial support and increased private sector participation. ‘We cannot focus on industrialization because without raw materials, there is nothing called industrialization,’ Mr Banjoko argues.

Meanwhile, the president of the All Farmers Association of Nigeria, Mr Kabir Ibrahim, wants the government to protect of oil palm farmers and palm oil producers by promoting local production and discouraging importation. ‘If we had protected our own industry, we would not be importing palm oil to Nigeria,’ He said, ‘We should protect our industries, we should promote what we produce locally, and then we can key what we produce into meeting our needs and then become a net exporter. That is the way to go.’

On his part, Mr Bright called on the government to organize retreats or trainings for smallholder oil palm farmers on how to maximize their oil palm plantations. He complained that many of the farmers lack the knowledge and equipment to fully maximize the resources in the oil palm fruits. Mr Alaje stressed that both the government and the private sector have major roles to play in reviving the palm oil sector. He suggested that the government develop a plan for the agriculture sector, especially as it has to do with palm oil. He urged the private sector to increase investment in the sector as demand for palm produce swells. He said:

The private sector should also see this as an opportunity, especially those in agro-business, as demand for palm produce has increased. So, instead of allowing manufacturers to import, it is important that we see it as an opportunity to invest in Nigeria. Those who do produce palm oil and other imported goods can also see it as an opportunity, especially those individuals in those areas, to see the opportunities to grow the area, so that at the end of the day, we can have improved revenues for both the private sector and also employment, which is one of the things that the government desires the most.

As Nigeria battles this palm oil paradox—depending on importation while being a major producer—these experts agree that redemption lies in combining modern research with targeted investment and reviving the once-vibrant spirit of Nigeria’s agriculture sector.

shop the republic

FUTURE OUTLOOK

Trade experts say a moderate boost in Nigeria’s palm oil production should be expected in the coming year. This expectation is based on the recent investment announcements and impressive profits announced by large-scale palm oil.

For instance, JB Farms, in 2022, acquired 10,000 hectares of land in Ore, Ondo State for an oil palm plantation. Also in 2022, the Ondo State government, during the administration of late Rotimi Akeredolu, supported palm oil farmers with ₦2 billion worth of loans and grants. This year, Okitipupa Plc, a major palm oil producing company, reportedly acquired four modern mills to boost its production capability.

It is expected that these and various other recent investments in the palm oil industry will boost production, but these investments are not enough to meet the level of current the top producers—Indonesia and Malaysia.

Restoring the country’s position in the palm oil value chain requires more than nostalgia. It demands a coordinated effort to support smallholder farmers, incentivize private sector participation, rejuvenate ageing plantations, and modernize processing infrastructure. Only then can Nigeria reduce its dependence on imports, strengthen its economy, and reclaim its lost glory as a leading palm oil producer⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N2 Who Dey Fear Donald Trump? / Africa In The Era Of Multipolarity

₦40,000.00