Photo illustration by Dami Mojid / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref: Chatham House, Présidence Bénin / FLICKR.

THE MINISTRY OF pOLITICAL AFFAIRS

The Tragedy of Buharism

Photo illustration by Dami Mojid / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref: Chatham House, Présidence Bénin / FLICKR.

THE MINISTRY OF POLITICAL AFFAIRS

The Tragedy of Buharism

Most of the coverage focused on Tinubu’s two years in office has conveniently overlooked the fact that the period also marks a decade of the All Progressives Congress (APC) in power. But this is less likely because no one understood the significance of such a decade; more likely, it is because to recognize its significance would require reflecting on two terms of former President Muhammadu Buhari, who was conspicuously absent from the mid-term celebrations and events. To acknowledge Buhari would also be to counter a prevailing narrative that this government has deftly tried to acknowledge and push: that the achievements it has recorded have been despite a poor foundation from a predecessor from the same party.

The party headquarters might still bear his name, but Buhari’s legacy and his politics are being systematically and carefully removed by a successor he reportedly did not want. His loyalists have been largely shut out of the party, with some joining the coalition seeking to defeat Tinubu. Buhari, who official reports indicate died aged 82 at a London clinic over the past weekend, might have issued the diplomatically supportive statement to mark the occasional milestone, but there is an apparent effort from the Tinubu administration to whittle his influence, to varying degrees of success.

A NEW HOPE

Most modern Nigerian politicians are difficult to associate with a clear ideology to warrant the ‘-ism’ that followers tend to use to show their support. Founding fathers Obafemi Awolowo and Nnamdi Azikiwe were often associated with distinct philosophies on social progressivism and post-colonial development, which was helped by the fact that they were writers and able to share their beliefs with their followers. Ahmadu Bello, whose story has been largely covered mainly in biographies, is similarly associated with northern development and conservatism, which belies the fusion of religion and state. However, describing recent leaders through a single ideological base is more challenging, primarily due to a need to compromise to achieve electoral viability.

While Buhari was not adept at presenting his beliefs as a coherent school of thought, it can be helpful to trace and situate the origins of his close allies and loyalists. As Sa’eed Husaini, a Nigerian political sociologist, has done, these can be sourced through the ‘Kaduna Mafia’, a group of self-described ‘radical conservatives’ that included Ibrahim Tahir, a spokesperson during Buhari’s 2003 and 2007 presidential bids and Abba Kyari, his first chief of staff from 2015 till his death in 2020. This school of thought, promoting a strong nationalist state that viewed corruption as an affront to fair and meritocratic growth, was anchored in conservative values and respect for traditional hierarchies.

Furthermore, Buhari’s less-than-collegial stint as military head of state (1983 to 1985), coupled with his reputation for fighting corruption, put him at odds with many of the country’s elite and made him a champion of the country’s poor and marginalised masses. As someone who reached the highest office through his efforts and reputation, he remained a symbol of what could be and this was referenced in his repeated presidential bids. It is also ironic that he was removed in 1985 by Ibrahim Babangida, himself the embodiment of elite camaraderie, who was often accused of entrenching corruption and a pliant elite.

This distinct ideological base, especially in an era dominated by market-led reforms under a new democratic dispensation, would eventually lead Buhari to create the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC) to achieve his aims. It also meant that when a left-leaning, progressive and socialist APC was presented, it was a suitable marriage of convenience. The party was an associate member of the Socialist International, the global grouping of left parties, and promoted welfare policies aimed at endearing itself to the poorest members of society. It also helped that, in framing an opposition to an unpopular People’s Democratic Party (PDP), it made sense to present a welfarist and socialist party that sought to redistribute the nation’s wealth to the millions who were not enjoying the national cake. Tinubu, leading a strong South West constituency, could also appeal to the favourable sentiments associated with Awolowo’s progressive policies in the old Western Region, which promoted affordable education and healthcare. Painting PDP as out of touch, especially in the wake of the 2012 Occupy Nigeria fuel subsidy protests, enabled APC to jump on a growing populist wave.

shop the republic

THE PHANTOM MENACE

Buharism as an idea and as a brand has suffered from two major factors. First, Buhari’s performance in office was largely discouraging and disheartening. Notably, the Tinubu administration has largely distanced itself from Buhari’s tenure, and by indices that Nigerians often cite, ranging from foreign exchange rate to inflation, the country was worse off after two terms of a Buhari presidency. Even if the idea was right, the execution has been largely criticized and seldom had defenders apart from those who served in that government. However, the second factor is due to a lack of nonchalance in embedding the ideology beyond merely a powerful officeholder, but rather one that party members imbibed. For example, Trumpism, a more protectionist and isolationist ‘America First’ policy, has overwhelmed and taken control over the Republican Party and shown how a president can weaponize the powers of the office to influence an institution. But for reasons that the former president probably knew best, this was not Buhari’s approach to governance.

This reluctance to define the party through his brand of leadership and his ideology affected APC. In times, it seemed like an arrangement had been made to ensure that the different blocs that created the party had their distinct representatives. Buhari, the presidential nominee, represented the defunct CPC; Yemi Osinbajo, the vice-presidential nominee, represented the Tinubu-led Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN) group; and John Odigie-Oyegun, the first national chair, was from the All Nigeria People’s Party (ANPP) group. Both Bukola Saraki and Yakubu Dogara, who deftly manoeuvred their ways into emerging as heads of both chambers of the National Assembly, were former PDP members who defected ahead of the elections. This tenuous arrangement would ensure no one felt short-changed while the party grew.

The constituent parties agreed on the mostly agreeable policies—economic liberalization, poverty alleviation and building a functional middle class. Ironically, these policies were also similar to PDPs, which meant that politicians shuttling between the two engaged in superfluous ‘ideological debates’ to defend their moves. Husaini also makes the argument that most of Nigeria’s political parties appear to have converged along centre-right policy positions, perhaps adding to the discourse that while there may be some ideology, there is no ideological difference between such parties. But even within this big tent, there were clear distinctions. While ACN governors pushed for considerable foreign investment and opted for increased privatization and more market-friendly policies, ANPP governors in Borno (Kashim Shettima), Yobe (Ibrahim Geidam) and Zamfara (Abdulaziz Yari) were largely handling security-related skirmishes. In contrast, Nasarawa’s CPC governor Tanko Al-Makura, primarily focused on physical infrastructure as a measure of performance. Even eventual Vice-President Osinbajo, who had been Tinubu’s attorney-general as Lagos State governor, would have been privy and involved in the active market-led reforms and less aligned with a Buhari with whom he ran.

Buhari’s influential chief of staff, Abba Kyari, and Mamman Daura, the éminence grise of his administration, would play key roles in ensuring that similar acolytes were placed in key positions. Babachir David Lawal, whose political and public service credentials were largely a litany of roles in the Buhari campaign, was appointed to the sensitive position of ‘secretary to the government of the Federation’. CPC loyalists retained key cabinet positions overseeing Agriculture, Communications, Education and Justice, emphasizing a desire to control more welfare and social provision roles. ACN was given mainly the more market-facing roles, but after Kemi Adeosun, Buhari’s first finance minister, resigned in 2018, the party was deprived of the opportunity to actually direct fiscal policy. A bigger irony is that Godwin Emefiele, appointed by Buhari’s PDP predecessor, would shape monetary policy and defer to Buhari’s whims to stay in post.

Within APC, it became very clear that Buhari was reticent to utilize his evident electoral appeal in shaping the structures to his will. In 2018, despite initially supporting Odigie-Oyegun’s stay as party chair, Buhari was eventually pressured by governors to support a change in party leadership. Another chair change in 2020, following disputes at various levels, led to a power struggle before the creation of a caretaker committee, led by a sitting governor, for nearly two years. The lack of influence and control likely contributed to the failure of many Buhari loyalists in their bids for party nominations ahead of the 2023 general elections. With no apparent ‘heir’ to the Buharist mantle, and no champion to ensure his ‘bloc’ was returned to power, even Buhari’s belated attempt to influence the outcome of the presidential nomination failed and ensured he was unable to dictate how the party would function after his departure.

Looming large over Buhari’s administration was Tinubu’s ubiquitous presence. After reportedly declining to be named as vice-president, owing to concerns over a same-faith ticket being used to amplify opposition narratives around Buhari’s extremism, he was allowed to nominate his replacement. But Tinubu’s influence in a government under a party he helped form was whittled down. He did not nominate other cabinet members, and there were reports of his former protégés being used to curb his influence in his home South West region. This reportedly came to a head when Buhari used a function to correct the term ‘national leader’ that had been ascribed to Tinubu in his presence. That term, which is usually reserved for presidents when a party is in power, must no doubt have played into any insecurities over Buhari’s status within APC. Whatever their divisions, Tinubu supported Buhari’s re-election bid before anchoring his presidential bid on the notion that it was his turn after bringing APC to power.

Buhari’s eight years as president have been thoroughly unpacked and analysed. There is no doubt about his political capital and appeal; while some may have questioned his capacity to govern, he presented an ideology that people bought into. But establishing an ideology goes beyond simply voicing it or being associated with the ideas. It comes down to execution, which appeals to doubters and leads to converts, and then to evangelists who carry the message long after the name sake is no more. There is no shortage of politicians today who still base their political views and ideology on former prominent figures from Nigerian history. What this means, in the case of Buharism, is that while Buhari’s record remains contentious, Buhari would have been able to avert as much scrutiny or criticism if a preferred successor had been chosen. However, his departure paved the way for the ascent of a man whose own ideology contradicted Buhari’s.

shop the republic

THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK

Tinubu’s election was the culmination of decades of work, and also the first time that a career politician had ascended to the presidency on the back of their ambition and politicking. Generals supported Olusegun Obasanjo because he was a former head of state, while Umaru Yar’Adua and Goodluck Jonathan were beneficiaries of Obasanjo’s attempt to impose reportedly pliable successors. Buhari might have been the most prominent political figure of his time, but he was not a politician and was the beneficiary of the convergence of mass civil disillusionment with PDP and the formation of a viable alternative. Tinubu, on the other hand, had to work hard to achieve his goal and was faced with considerable opposition at almost every turn.

Tinubu’s legacy will likely be shaped by his efforts to end Buharism. This is both the mythos of the former president and his ideological positions. At almost any given point, Tinubu’s appointees have been quick to blame the Buhari administration for the difficulties they have faced, ranging from economic to security issues and the general state of affairs, presenting a challenging situation. Even Buhari’s signature anti-corruption sentiment was not a significant factor in the election for his successor, with a clear break from his approach to governance a major consideration.

Tinubu stacked his cabinet with campaign loyalists, including frontline opposition member Nyesom Wike, while dispensing with many top-ranked politicians who had served under Buhari. He was also swift with changing party leaders, removing Abdullahi Adamu and Iyiola Omisore, Buhari’s pick as party chair and national secretary, and elevating Abdullahi Ganduje, a key ally who was a mainstay during his campaign. Unlike his predecessor, who was content to refrain from getting involved in state-level politics, Tinubu has actively gotten involved in campaigns and ensured that key governorship polls were won to prepare for his re-election bid. Nigerian politicians are typically adept at pivoting accordingly to ensure their fortunes remain secure, but the speed with which the party has fallen in line behind Tinubu demonstrates how quickly and effectively he has consolidated power.

These moves have not been without some prominent resistance within the party. Nasir El-Rufai, former Kaduna State governor and Tinubu ally turned critic, has since defected to join another opposition party. Rotimi Amaechi, a former minister and runner-up in APC’s presidential nomination contest, has declared another presidential run as a member of an opposition party. Abubakar Malami, Buhari’s influential attorney-general, received criticism for slamming APC’s endorsement of a Tinubu second-term bid and has since joined an opposition party. Even Buhari himself had to state that he was not leaving the party, amidst rumours that his bloc had felt neglected under the new state of affairs. This is not without precedent; ahead of the 2019 elections, both heads of the chambers of the National Assembly defected to PDP, but even then, the party was able to maintain its appeal.

Yet the biggest theatre of conflict for any attempt to eviscerate Buharism remains the populous north, where the former president is still largely revered and where no clear successor has emerged. Tinubu’s imbalanced appointments, which have drawn comparisons to Buhari’s, have led to campaigns among northern politicians to correct the ‘error’ of allowing power to go to the south. This presents two key clashes between the two bodies of thought. One, Buhari’s appeal never truly resonated with the region’s elite, while Tinubu’s considerable political network is anchored in strong ties with the country’s patrician class. A second Tinubu success could neuter the symbolism that Buhari’s victory presented, especially if, as expected, elite consensus becomes a more sustainable and recurring template. Tinubu’s political approach might also be made or marred by intra-northern responses to potentially replacing Kashim Shettima as his running mate for the 2027 elections, which already led to a tumultuous caucus meeting in Shettima’s North East zone. Other northern politicians eyeing the vice presidency might play a spoiler role, allowing Tinubu to divide and conquer and stave off coalition efforts. Either way, this does not align with the notion of an influential North, which was a major appeal behind Buhari’s politics and rise to power.

Two, Buhari’s electoral appeal was concentrated mainly in the populous North West and conservative North East zones, relying on the wider APC structure to break into the South and build on decent numbers in the North Central. Conversely, it was the North Central that was the anchor of Tinubu’s election victory. PDP’s Atiku Abubakar was stronger in the North East and won more states in the North West, albeit having a roughly 325,000-vote deficit to Tinubu owing to a poor showing in Kano. Tinubu’s strong showing in the North Central and Peter Obi’s stronger-than-expected performance relegated Atiku and PDP to third in the zone and all but ensured Tinubu’s victory. Already, opposition politicians are banking on being able to field a strong northerner to take over the Buhari coalition. Tinubu’s campaign appears geared at strengthening his appeal in the South-South, where two PDP governors have already defected to APC, and leveraging his strong ties with the South East, where another opposition governor, Charles Soludo of Anambra, has already endorsed Tinubu for re-election. Building on this base and succeeding could end the sentiment of a ‘king in the north’ in electoral politics. Prominent politicians such as Kano’s Rabiu Kwankwaso and Sokoto’s Aminu Tambuwal remain viable alternatives in the future, but the popularity of both former governors remains largely restricted to the states they governed.

A second Tinubu term could lead to an even stronger consolidation of his political structure within the party, similar to his firm grip on Lagos politics. It could enable him to reshape APC along a more market-friendly line, focusing on upscaling the middle class while building elite consensus at the expense of a focus on poverty alleviation and social welfare policies. There’s already a stronger focus on ceding more responsibility to subnational units, as seen through the proliferation of regional commissions and the push to strengthen local government autonomy, which would enable a wealthier centre.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

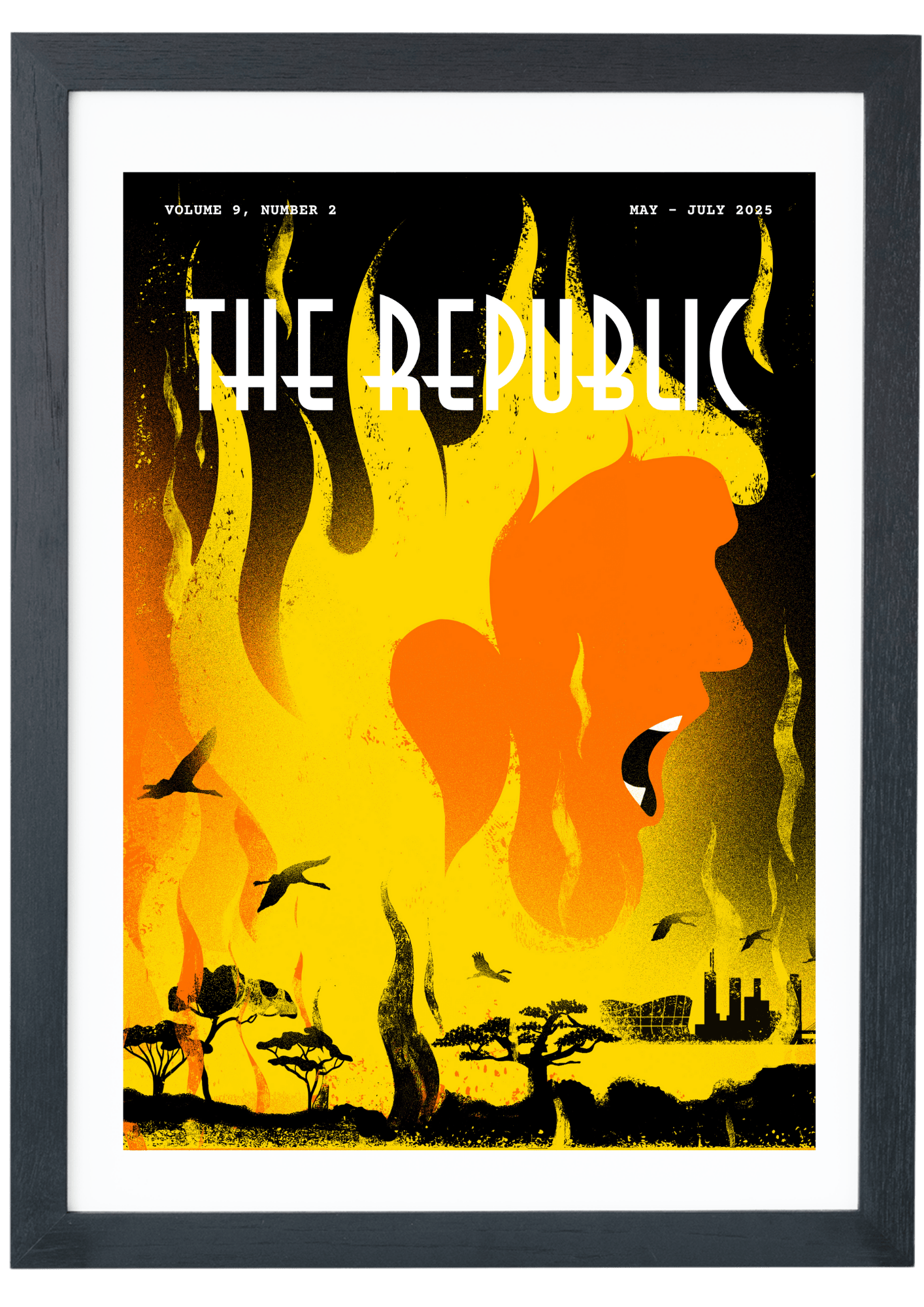

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

shop the republic

THE LAST BUHARIST

Despite not featuring during this round of self-congratulations and glad-handing, Buhari’s legacy and recent death will reshape calculations and permutations for the 2027 elections. Politicians will jostle to present themselves as the rightful heir to the Buhari coalition and tie their candidacies, to varying degrees, to his legacy. He was one of the most popular politicians in the country, and the idea of who he would have supported will still carry significant weight. There is also the argument that even if his ideologies don’t persist in name, they will carry on in some form as long as APC is in power. After all, Tinubu’s first significant policy rollout was the creation of a student loan programme that could easily have been delivered under his predecessor.

Yet, Buharism, as an idea and a concept, is quickly losing its adherents. This reflects the prevailing political sentiment of a now-transient political culture, one that pivots in the direction of whose mandate people stand on. The myth of an incorruptible strongman who could change Nigeria has been dented, giving way to the growing belief that politicking and proper elite consensus is now the only viable ladder to the top job.

But there is an irony in the final standard bearer of his ideas. The closest comparison to a Buhari today is Obi, a candidate whose opponents peddle the narrative that he is a sectional champion and whose supporters preach his appeal to the masses and his ability to remain untarnished despite being a politician. Like Buhari, Obi left a well-known political party and went to a less structured one to prove his viability. Like Buhari, whose supporters proudly claimed to be Buharists, Obi’s Obidients continue to preach the merits of his candidacy wherever they can. Like Buhari, Obi’s limitations in becoming president lie from being marred by successful opposition campaigns of calumny across the Niger. Obi’s contested record as governor of Anambra will also inspire his supporters in his ability to govern Nigeria, just as Buhari’s brief period as head of state was cited during his campaigns.

However, herein lies the most critical contribution that the Buhari era, and indeed a decade of APC rule, gives to Nigerians. Electoral power has evolved from the era when political philosophy was actively studied and cited; today, the transactional and compromizing nature of our politics means that it is less firm and consistent. It means that seeking heroes in this mould is an ultimately foolhardy task, and it is more necessary to work on structures and building institutions to make a truly national consensus the foundation for public service to build on. It calls for a truly national conversation and a considered effort to counter disinformation campaigns that foster division, especially since there are more shared challenges that transcend sectional and regional interests. It also involves believing in and working towards electoral reform, as well as undertaking the necessary tasks to address citizen apathy and cynicism about their role in a democracy. The tragedy of Buharism is not necessarily that it succeeded or failed; it is that it has simply shown there is and will be much more work to be done⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N2 Who Dey Fear Donald Trump? / Africa In The Era Of Multipolarity

₦40,000.00