Illustration by Sheed Sorple Cecil / THE REPUBLIC.

THE MINISTRY OF ARTS / PEOPLE DEPT.

On Meeting Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

Illustration by Sheed Sorple Cecil / THE REPUBLIC.

THE MINISTRY OF ARTS / PEOPLE DEPT.

On Meeting Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

San Francisco, 7 October 2012. The audience perched on the edges of their seats, voices rising in collective, animated chatter. Then suddenly, joyful street music spilled through the second-floor windows of the Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD), as though the city itself knew. Literary titan, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was in the house! Months of planning with MoAD and Litquake—the Bay Area’s largest literary festival—had led to this moment, and now, as I prepared to moderate, I felt a familiar tremor of excitement. The Nobel Prize for Literature would be announced within days. Could it, would it, finally be Ngũgĩ’s year?

NGŨGĨ IN PUBLIC

For a world of connections and interconnections in a non-hierarchical way.

—Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, book inscription in Globalectics: Theory and Politics of Knowing

My very first glimpse of Ngũgĩ came in May 1999 at Cambridge University: just flashes of his shirt, a short man nearly swallowed by an admiring crowd. I was visiting Cambridge as part of my doctoral research at Berkeley to conduct an interview with a young Ghanaian academic, Ato Quayson. But my scholarly agenda quickly dissolved upon learning Ngũgĩ would be delivering Clare College’s annual Ashby lecture. He was the first African literary ‘rock star’ I would encounter, and I could hardly wait.

In Cambridge’s grand Robinson College auditorium, Ngũgĩ’s small, slightly hunched frame belied the power of his lecture titled: ‘Universities and the Magic Fountain: African Literature into the 21st Century’. His hands danced to his words as he spoke in his trademark Gĩkũyũ-accented English, arguing forcefully for indigenous African languages as Africa’s medium of instruction. I marvelled at the large audience gathered to hear him and felt a surge of continental pride.

A few years later, I would meet, and this time, speak with Ngũgĩ at the 2006 annual African Literature Association (ALA) meeting in Accra, Ghana. He was there to give a plenary talk, coinciding with the release of his long-awaited English translation of his novel, Wizard of the Crow. It was the first ALA meeting held on the continent in years, and audience excitement was palpable.

In photographs taken from the conference, Ngũgĩ stands between other writers and academics wearing an emerald green Kitenge shirt, his arresting, deep-set eyes that seem to drift, his beard sparse and stubbly. All of us beam for the camera, but Ngũgĩ has that slightly haunted, faraway look in his eyes.

While celebratory, the conference carried a sombre undertone. Just two years earlier, Ngũgĩ and his wife had suffered a horrific, politically motivated attack during their return to Kenya after years of forced exile. Ngũgĩ’s wife, Njeeri, had been raped in the attack. The trauma reverberated in hushed tones among conference participants. I remember watching Ngũgĩ and wondering how he was coping in the aftermath. I also thought about how politically motivated violence had affected the families of other celebrated writers such as Wole Soyinka, Denis Brutus and Ken Saro-Wiwa. I thought especially of Ngũgĩ’s wife, Njeeri, whose decision it had been to go public with her assault. Yet despite the traumas he carried, in public Ngũgĩ remained as committed and passionate to his causes as ever. When I spoke with him, his approachability struck me—never rushed, never scanning for more important people to speak with, just genuinely present and energized.

Six years later, this time at my invitation, Ngũgĩ brought to San Francisco in 2012 that same passion and generosity I’d witnessed in Accra. On stage, we spoke of his new book and his language concerns, punctuated by his wry humour. ‘Can you imagine Italian literature taught only in Zulu? How absurd!’ Near the end, I asked for advice for budding writers. He smiled and paused dramatically: ‘Writing is very simple. So, I’m going to give you the formula.’ The room went silent, pens poised. ‘You can write, write, write again, and you will get…it…right.’ Joyful laughter erupted. Even as time ran out, he gave full, considered answers to every audience question.

I’ve met many literary greats from Ngũgĩ’s generation, but few have been as generous as he, not just toward me, but to everyone. At the 2016 Aké Arts and Book Festival in Abeokuta, Nigeria, I watched him patiently posing for numerous selfies and welcoming anyone to join him for lunch with his egusi and palm wine. At one of the festival’s most festive evening events, he delighted in a multilingual performance of his most translated short story, ‘The Upright Revolution: Or Why Humans Walk Upright’, dancing in the audience with such joy and exuberance. At another book event in San Francisco in 2019, just before he began his talk, he called out Zambian-American writer Namwali Serpell and me, highlighting us to the audience as writers to read. His passionate interest in everyone truly embodied a principle he lived by, as he wrote when he signed my copy of Globalectics: ‘For a world of connections and interconnections in a non-hierarchical way.’

DISCOVERING THE LANGUAGE WARRIOR

How did we, as African writers, come to be so feeble towards the claims of our languages on us and so aggressive in our claims on other languages, particularly the languages of our colonization?

—Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature

It was in the mid-1980s in Nairobi, as a teenager, that Ngũgĩ first entered my consciousness. I knew he’d been imprisoned and exiled under Kenya’s dictator Daniel arap Moi for criticizing the government through his plays, but I wouldn’t read his work until years later while studying African Literature at Birmingham University. I began with his novels, Weep Not Child and A Grain of Wheat. Having lived in Kenya, I found their historical backdrop particularly compelling, though the stories themselves didn’t captivate me as much as his nonfiction. It was Decolonizing the Mind that truly struck me, laying bare the insidious effects of what, in his Cambridge talk, he termed ‘Europhonism’—the displacement of African languages and cultural memory by colonizing languages and cultures.

Like many university students, I studied Decolonizing the Mind alongside Chinua Achebe’s essay ‘The African Writer and the English Language’, weighing where I stood between the two literary titans. Ngũgĩ argued for urgently reclaiming African languages, while Achebe championed English as an African language offering both communicative ease and unique possibilities to ‘Africanize’ it. I found merit in both writers’ perspectives.

I couldn’t deny Ngũgĩ’s point about the linguistic marginalization of African languages or his lament that intellectual production in Africa was almost exclusively done in European languages. His arguments resonated all the more deeply given my own inability to speak Yoruba, my father’s tongue. I admired Ngũgĩ’s principled decision to write new books in Gĩkũyũ first—a choice clearly not merely academic. It was, after all, his Gĩkũyũ play Ngaahika Ndeenda—not his earlier works in English—that led to his detention by the Kenyan authorities.

Yet, coming from Nigeria, a nation of several hundred languages, I appreciated English as a unifying lingua franca. This same appreciation had led me to study French, unlocking other continental experiences. Like Achebe, I delighted in how Africans’ English enriched English itself. Re-reading Ngũgĩ’s novels years later, my eager pencil marks from earlier readings highlight how much I loved the rich, vivid imagery with which he infused English. In A Grain of Wheat, people appeared ‘like clusters of locusts perched on trees,’ the train became ‘the iron snake’ and guns, ‘bamboo poles that vomited fire and smoke.’

Though I could never write in an indigenous African language, Ngũgĩ’s advocacy inspired my support for translation and publishing in these languages. One memorable project was collaborating on a groundbreaking online anthology led by my publisher, Bibi Bakare-Yusuf, at Cassava Republic Press. In this 2015 Valentine’s Day collection, seven African writers had short stories translated into their mother tongue—or, in my case, father tongue: Yoruba.

shop the republic

This commitment to African languages and to a radical rethinking of literary exchange, as described in Ngũgĩ’s Globalectics profoundly influenced my 2016 decision to grant my Nigerian publisher, Cassava Republic Press, world rights to my second novel rather than granting rights to a Western publisher first. Ngũgĩ’s example, grounded in a careful consideration of power structures and dissemination, resonated with my growing understanding of how stories travel and who controls their journey.

Inspired by Ngũgĩ’s literary activism, I embarked on other projects aimed at amplifying fresh perspectives from young African writers’ voices. One such project was co-editing Pulsations: The Journal of New African Writings with novelist and scholar Patrice Nganang. We published with Africa World Press from 2011 to 2012 in both French and English and welcomed pieces in indigenous languages too. I was particularly excited about bridging the linguistic divide between Francophone and Anglophone African writers, but literary activism proved challenging. The funding, publishing, and audience-building hurdles were significant; our journal lasted only two volumes.

In 2017, Patrice’s own courageous activism—speaking out against state-sponsored violence toward the English-speaking minority in Cameroon—landed him in a Cameroonian prison and, like Ngũgĩ, in exile.

STORYTELLER AMONG STORYTELLERS

Stories, like food, lose their flavour if cooked in a hurry.

—Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Wizard of the Crow

Ngũgĩ’s role as a language warrior and publishing revolutionary was inextricably tied to the importance of storytelling. He was a master storyteller, especially drawn to oral storytelling, and this side of him sparkled in our personal encounters. Naturally, I began our 2012 public conversation by asking about storytelling. I’d invited Ngũgĩ’s son, Mũkoma wa Thiong’o, also a writer, to share the stage with his father, and this seemed to elicit an outpouring of stories from both, at times a melodic call and response between father and son. Mũkoma described their family storytelling traditions, illustrating with hilarious tales featuring Mwangi the cowboy. Ngũgĩ added his own story—theatrically covering his eyes—featuring his youngest daughter, Mumbi, ‘far more down-to-earth’ than her siblings, who was completely mystified by her father and brothers’ imaginative tales. Laughter rang through the audience.

After the event, the magic continued when Ngũgĩ, his youngest son Thiong’o, and Mũkoma joined us for dinner at our home with friends and fellow writers Anne Whiteside, NoViolet Bulawayo, and Nozipo Maraire. After dinner, the storytelling began in earnest. Ngũgĩ, holding court from the head of the table, read an unpublished story written for Mumbi about shadows and sibling rivalries that would later appear in his 2019 collection, Minutes of Glory: And Other Stories. Behind him, Mũkoma’s blues guitar hummed softly. NoViolet lent her contagious giggle to the melody.

What struck me that night wasn’t just Ngũgĩ’s storytelling prowess, but how deeply he listened to others. He seemed as enthralled with our stories as we with his. Pure playfulness filled the night, and everyone shared. The Ngũgĩ sons read excerpts from their works, Nozipo from her acclaimed novel Zenzele: A Letter for My Daughter, while Anne recited a William Carlos Williams’ poem, ‘This is Just to Say’. Looking back, there was something almost prophetic—two of us would transform the stories we shared that night into books. NoViolet’s Caine Prize-winning short story ‘Hitting Budapest’ became part of We Need New Names, and my story ‘Morayo’ grew into Like a Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun.

In 2019, Ngũgĩ joined us for another dinner with his grandson Miringu and several of our friends—writers, academics and researchers. This time, Ngũgĩ regaled us with tales from his Makerere University days—meeting Langston Hughes, guiding him through Kampala during the legendary 1962 African Literature Conference, where literary stars like Achebe, Ama Ata Aidoo, and Gabriel Okara all converged. Then came the beautiful back-and-forth: his historical lens sparking stories and conversations that danced across continents and eras.

The evening unfolded with typical serendipity. Harry Elam, the distinguished African American theatre professor, spoke of August Wilson and social theatre’s power, resonant with Ngũgĩ’s own imprisonment for his plays. Namwali Serpell’s account of the 1960s Zambian Space Programme (which she’d recently published in The New Yorker) clearly fascinated Ngũgĩ, while Michele Elam, a James Baldwin scholar, talked about Baldwin’s ‘welcome table’ which seemed to perfectly capture the inclusivity Ngũgĩ embodied. When my husband, James, shared how his own father had not only attended a Baldwin reading at the Strand bookshop in New York but also corresponded with the very Zambian ‘afronaut’ Namwali described, Ngũgĩ’s eyes lit up. These intellectual connections bridging continents and eras felt like extensions of his own expansive worldview.

Ngũgĩ was suffering from a cold that night and, knowing his love for tea, I made him many cups of ‘Bibi brew’, named for my publisher who once saved me with it on a book tour. Bibi’s warm brew—cinnamon, ginger, honey and lemon—worked its magic for Ngũgĩ that night who, despite all the talking, thankfully never lost his voice.

A LITERARY FRIENDSHIP

Keep strong; keep writing.

—Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, email exchange, August 11, 2021

Scrolling through these digital letters, I’m struck by what they reveal of Ngũgĩ’s deep curiosity as a reader and his generous insights as a writer. Sometimes we’d exchange quick messages over consecutive days, more often months would lapse between correspondence. Here’s one dated October 1, 2017, in response to me asking whether he’d read Saramago’s Blindness:

I started reading Saramago’s Blindness, but did not finish it. I got to where one of the women, not blind, but covers her eyes so that she inhabits the same blind space as her husband (not sure!) but it reminded me of Mahabharata where one of the brides to be to Dhrahatsra (?), the blind king to be, does the same thing: has her eyes completely covered so she is in the same sphere. And I was thinking: Was Saramago impacted by the Indian epic?

Here is Ngũgĩ’s mind at play—seeing patterns across Portuguese literature and ancient Sanskrit epics, always questioning, always connecting. In another delightful exchange from 22 January 2018, he bubbles with excitement about an ongoing family writing contest.

Mũkoma, his three siblings, Nducu, Bjorn, Wanjiku and I are in a family contest: writing a piece located in Kings Hotel in Stockholm and involving two glasses of wine (two different brands) But from the same location, the characters’ story and the characters can move anywhere. Okey Ndibe of Nigeria has also entered the contest on the basis that Mũkoma is his writer-brother. I have just finished mine: The Glass Struggle in Stockholm. Contestants can write in their language of choice (I did mine in Gĩkũyũ; Okey Ndibe wants to do his in Igbo!), but there has to be an English translation.

The contest rules embody Ngũgĩ’s core philosophy—championing indigenous languages while ensuring accessibility through translation. His fervent enthusiasm for translation is evident in several exchanges. In August 2021, he animatedly describes the work of Jane Bosibori Obuchi, ‘who has now translated and published Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart; Ngugi (I will marry when I want) and even Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet into Ekegusii,’ and Boris Abubacar Diop, ‘who is publishing the Wolof translations of classics of Black Thought such as Frantz Fanon.’ He also mentions John Mambambo for his translation of Decolonizing the Mind into ChiShona.

Yet, alongside this excitement, Ngũgĩ is also candid about the difficulties surrounding translation. In 2017, he confides a ‘continuous struggle with Gĩkũyũ, no, not so much the language, but the colonial mountain in the mind of my publishers who have sat on several of my Gĩkũyũ language manuscripts for years.’

On 17 January 2021, he draws a new connection, hinting perhaps at a slight turn or broader understanding of cultural resistance: ‘You remember C.L.R. James in his book The Black Jacobins? That Revolutions are often led by those who have gained certain advantages from the culture of the oppressor. I suppose because they are able to see it more clearly.’

Our correspondence is also a source of writerly encouragement to me. When I share my interview with Morrison, conducted together with writer, Mario Kaiser, Ngũgĩ writes back with such warmth, declaring it ‘the literary coup of the year.’ His follow-up still makes me smile: ‘I really really like your interview with Toni Morrison. It is as beautiful as it is insightful. She is so much alive, how did you two manage to draw her out so?’

19 March 2019 brings another heart-stopping moment when Ngũgĩ writes to tell me how much he’s enjoyed my debut novel, In Dependence, offering a blurb for the tenth anniversary re-issue.

Dear Sarah, I could not keep it down. I read it between Irvine and New York, where I had gone to help promote my book of old and two new stories, Minutes of Glory. And now that I am in the Sarah Manyika universe, I have asked Barbara to order, Like a Mule Bringing Ice-cream…, so I can read it before the muse makes me withdraw into my own world. Once again, congratulations.

Such words of encouragement always lifted and energized me—a generosity I know he extended to countless other writers.

shop the republic

shop the republic

shop the republic

-

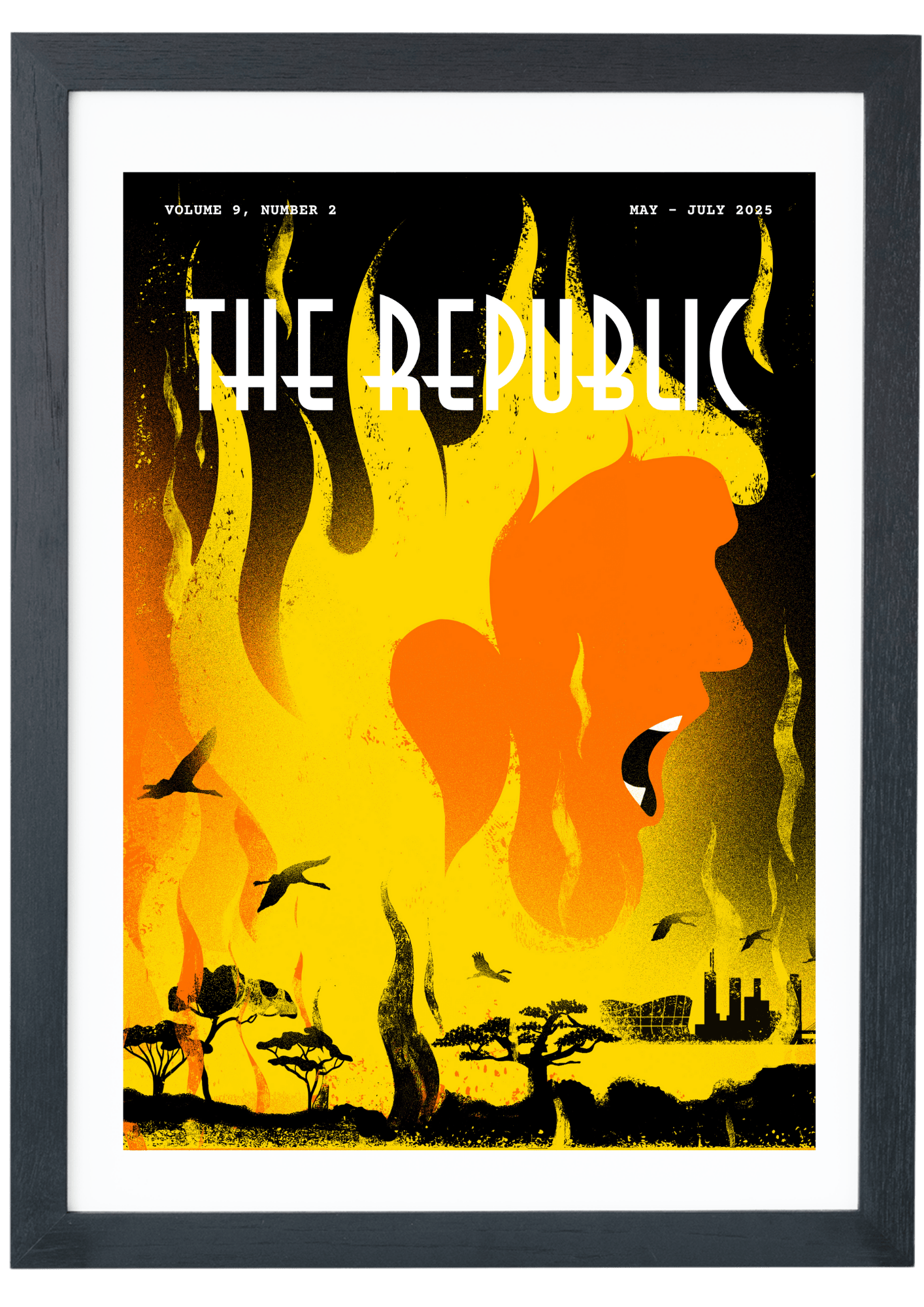

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Yet even as he’s encouraging, his letters occasionally reveal a touching openness about his own creative struggles. After I share an article by Suyi Davies Okungbowa that includes Ngũgĩ’s Wizard of the Crow in a curated list of must-read books, Ngũgĩ replies with disarming honesty on February 3, 2018: ‘Thank you, by the way, for the write up on Wizard of the Crow. It was a timely reminder that I should embark on a novel (Alas no muse yet).’

During the pandemic’s uncertain early days in April 2020, Ngũgĩ reaches out with his poem ‘Dawn of Darkness’:

Dawn of Darkness (One of the rare ones in English, my poetry is mostly in Gĩkũyũ) Please feel free to share it, as you see fit. The poem has not been published, it is circulating from person to person, and these days, with the social media as a kind of cyborality, the poem has traveled quite a bit. We are all in this together, and if this does not teach anything about the links that bind us, to use the Dubois words, I don’t know what will. Keep writing more novels.

I continue sharing my writing with him, including my ‘On Meeting’ profile of pioneering publisher Margaret Busby, someone he’d known since the 1980s. After reading it, Ngũgĩ expresses an eagerness for me to write about him, something I was equally keen to do. But this was during Covid, so thoughts of an in-person interview along the lines that I had done with my visit to Morrison’s home, would have to wait.

Alas, that meeting never happened.

COMPLEXITIES OF A LIVED LIFE

People try to rub out things, but they cannot. Things are not so easy. What has passed between us is too much to be passed over in a sentence. We need to talk, to open our hearts to one another, examine them, and then together plan the future we want.

—Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, A Grain of Wheat

As years passed, Ngũgĩ’s fragility became more apparent. ‘My dialysis does affect my moods and general performance,’ he admitted via email, ‘but it enables me to breathe.’ (11August, 2021).

In his last two years, we spoke by phone occasionally; brief calls that felt increasingly precious. Once, not long after his second divorce, he repeated, almost to himself it seemed, ‘don’t ever get divorced, divorce is terrible.’ Another call revealed his delight at living with his daughters, his voice brightening as he marvelled at the beauty of nearby trees. Tentatively, we resumed talks of a visit.

His final voicemail (December 23, 2024) was painfully brief, his words slightly slurred. It arrived while I was travelling. Knowing he was very ill, I wanted to return his call, but felt I should speak with his family first, particularly Mũkoma, the son I knew best.

Mũkoma had recently shared, via social media, painful memories from childhood of his father being physically abusive to his first wife (Mũkoma’s mother). Ngũgĩ had never publicly addressed these claims, and I struggled with this knowledge. The allegations stood in stark contrast to the man who championed the oppressed—who had written so movingly in his memoir, Dreams in a Time of War, about his own mother’s experience with domestic violence.

I told myself I was waiting for the right moment—perhaps I’d consult with Mũkoma first about approaching his increasingly frail father. But the truth was I was wrestling with how to reconcile the man whose encouragement had meant so much to me with what Mũkoma had posted. Weeks passed. Then months.

I have no deeper insight into Mũkoma’s troubling allegations than anyone else, but the question haunted me: How do we honour warriors without erasing the harm they may have caused? Perhaps this is what separates a literary relationship from hero worship—the willingness to sit with complexity. While writing about literary figures, it’s tempting to focus solely on their public contributions. Yet real people, even literary giants, embody contradictions and lead complex lives.

Now, thinking back to the father and son discussion of 2012 at MoAD, something new strikes me. Following Ngũgĩ’s advice to budding writers to ‘write, write, write’, Mũkoma had offered a playful dissent, paraphrasing Baldwin’s simple desire to write well and be an honest man. I’ve long admired Baldwin, and Notes of a Native Son—the work to which Mũkoma was referring—has repeatedly inspired me. In it, Baldwin, reflecting on his father’s death, speaks of the necessity of holding seemingly contradictory thoughts—remaining committed to fighting injustice while keeping one’s heart free of hatred and despair.

I never did return Ngũgĩ’s last call. How I wish I had.

I would have thanked him for his kind wishes. I would have wished him a happy New Year and birthday. And I would have wished him peace. Had I known it to be his last year, I would have reiterated my desire to write about him, expressing how much his storytelling, encouragement, and courage meant to me. I would have told him how I’ve embraced his simple formula—’write, write, write until you get it right.’

Now I respond the only way I know how: by writing about the Ngũgĩ revealed in his work and our interactions—the champion of African languages and mentor of young writers—and the man whose private actions may have fallen short of those public ideals. This, too, is part of his story—part of what it means to write honestly, not perfectly, but with the courage to hold multiple truths simultaneously. As Toni Morrison reminded us in her Nobel lecture, there are many things language alone cannot do, but ‘its force, its felicity is in its reach toward the ineffable.’ In reaching toward the ineffable complexity of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, I find both the beauty and the profound challenge of bearing witness to a human life⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N2 Who Dey Fear Donald Trump? / Africa In The Era Of Multipolarity

₦40,000.00