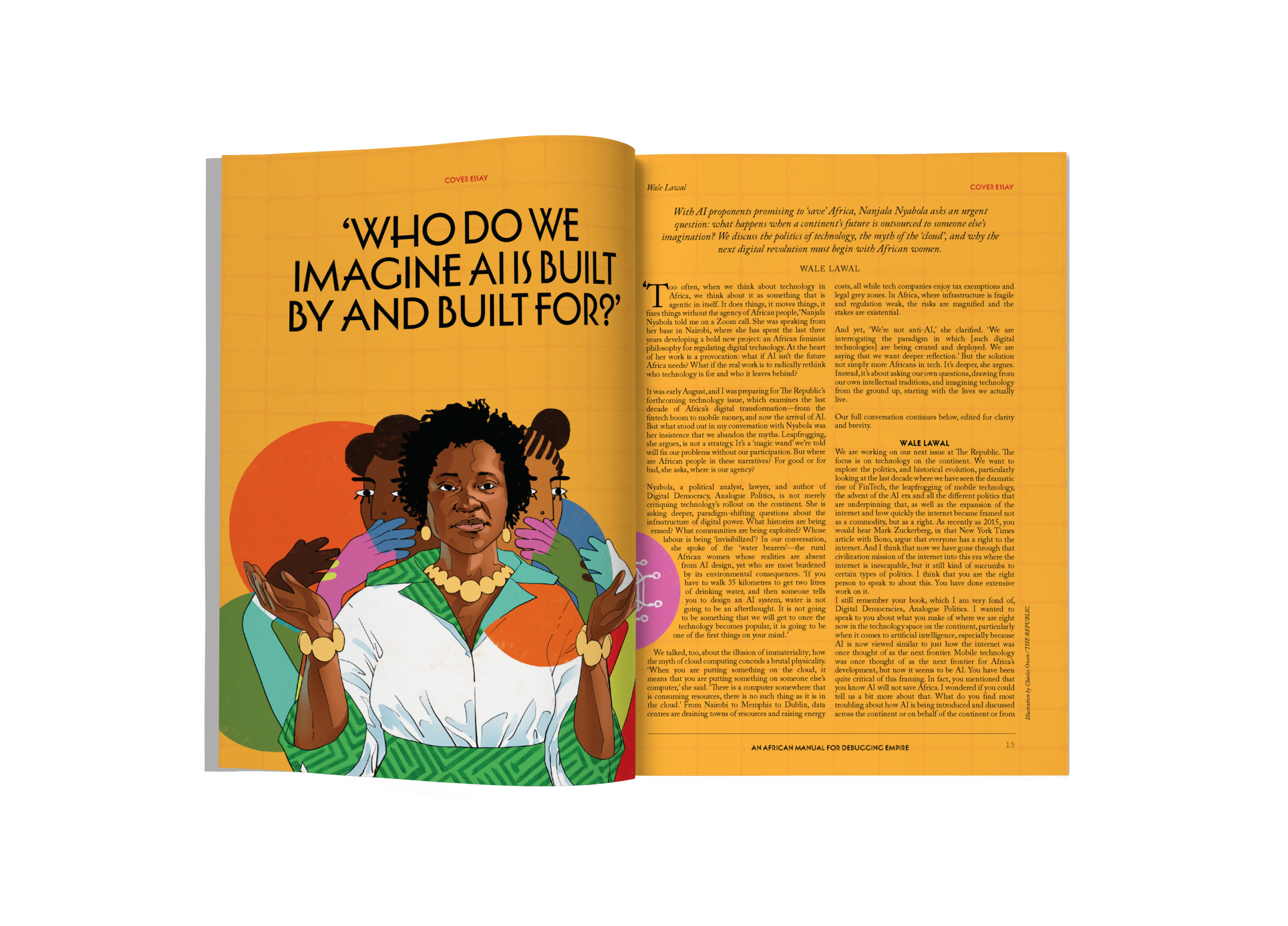

Photo illustration by Michael Emono / THE REPUBLIC.

THE MINISTRY OF GENDER X SEXUALITY

African Feminist Futures Beyond the UN Workshop Industrial Complex

Photo illustration by Michael Emono / THE REPUBLIC.

THE MINISTRY OF GENDER X SEXUALITY

African Feminist Futures Beyond the UN Workshop Industrial Complex

This year, 2025, the United Nations (UN) turns eighty. For African women, the anniversary may invoke paradoxical emotions. On one hand, the influence of African women’s organizing on policy discourse is a cause for celebration. On the other hand, African women are still forced to grapple with the unrelenting continuities of power that have shaped their participation from the very beginning. While the UN remains a critical avenue for African feminist diplomacy, its ‘empowerment project’ on the continent has been an impediment to true structural transformation.

Across South Africa, Liberia and Sierra Leone, National Action Plans (NAPs) under UN Security Council Resolution 1325 have generated endless workshops but little redistribution of power. The ‘woman participant’ of UN workshops is a fabrication of donor discourse. She is vulnerable, trainable, and perpetually in need of capacity building. Such practices do not merely represent gender—they produce it. In privileging ‘women’ as a policy category, the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda reproduces subject positions of victimhood and peace-building competence while sidelining other axes of power such as race, class, and sexuality.

Rather than evaluating the effectiveness of specific UN policy initiatives, I choose to interrogate the productive power of the UN’s workshop industrial complex and the donor-driven model it sustains. I ask, how do workshops, log-frames, and indicators function to fabricate a particular kind of African woman who can be measured, trained, and displayed for prime-time news?

GENEALOGIES OF AFRICAN WOMEN’S ENGAGEMENT WITH THE UN

African women were ‘invented’ under colonial regimes as a docile, domesticated, apolitical ‘other’. Their absence from San Francisco during the signing of the UN Charter in 1945 was therefore unsurprising. At the time, women were largely illegible in human geography and it was widely assumed that they could not contribute to the emerging global rights framework. Yet, in parallel with this early exclusion from multilateral relations, African women began sowing the seeds of transnational, pan-African organizing.

At the 1958 All-Africa People’s Conference held in Accra, Ghana, women leaders discussed the possibility of a continental women’s organization that could address the liberation of both African nations and African women. Soon, these ambitions extended to the UN. In 1961, during the 16th UN General Assembly (UNGA), Angie Brooks (Liberia), Cisse Keita (Guinea), and Judith Imru (Ethiopia) raised proposals on issues such as the minimum age of marriage, mutual consent in marital relations, and broader political rights. Their interventions were sometimes met with resistance from male delegates who invoked tradition or national interest, but they signalled an important step toward African women’s participation in shaping international discourses.

To streamline their engagement, the Pan-African Women’s Organization (PAWO) was established at the Fourth All-Africa Women’s Conference (1974), in Dakar, Senegal. PAWO would be a solidarity platform for African women to mobilize efforts towards liberation from apartheid and colonialism. Its agenda was centred on African women’s cultural, economic and social concerns, while drawing connections between the continent and the diaspora. In a 1974 New York Times article, which covered the conference, a participant is quoted saying, ‘African women are beginning to understand that the all-encompassing seriousness of our struggle demands that they fulfil a vital and necessary role in the movement to put power and wealth in the hands of the people.’

Subsequently, in 1975, the first World Conference on the Status of Women was convened in Mexico. This was also International Women’s Year, commemorated as a reminder that discrimination against women is a persistent global issue. The UNGA had earlier declared 1976-1985 as the United Nations Decade for Women, which marked a new era in global efforts to promote gender equality and the advancement of women. During this decade, two other world conferences were held in Copenhagen, Denmark (1980) and Nairobi, Kenya (1985).

African women were engaged in international policy discourse from an organized and politically conscious position. They unsettled the UN’s technocratic scripts by shaping their politics on the lived urgencies of apartheid, colonial residues, and the daily struggle for land and food. During the Mexico City and Copenhagen Conferences, many ‘third-world women’ were dissatisfied with the imperialist insistence of a universal gender oppression, as it was experienced and articulated by Western feminists. Their discontent hinged particularly on the overemphasis on the inequality between men and women, which inadvertently overshadowed race, class and global inequalities. Echoing the sentiments of the earlier quote, African women reaffirmed their capacity to wage their own struggles and rejected the ‘white saviour’ imposition.

The Nairobi Conference (1985), held in Kenya, held contextual and political significance for women from the Global South. It provided a more appropriate setting to voice grassroots concerns and expose the dissonance between UN rhetoric and local realities. African feminists built networks constituting activists, policy makers and scholars, which Prof. Funmi Olonisakin, Prof. Cheryl Hendricks and Prof. Awino Okech later referred to as the three pillars of influence in gender and security. African delegations particularly insisted on including structural adjustment, militarism, and global economic injustice as women’s issues. This flared up tensions with Western feminists who were more concerned with language on sexuality and legal equality. This contention culminated in the Nairobi Forward-looking Strategies, which acknowledged the plurality of women’s struggles and the intersection with coloniality.

Here, African women are seen actively recrafting UN language. At the following world conference in Beijing, China (1995), African women were no longer at the margins. They organized in caucuses that negotiated as a bloc, and pushed the Platform for Action to recognize poverty, violence, and conflict as central to gender equality. It is important to note that the closing decades of the twentieth century introduced new dynamics. Economic liberalization, structural adjustment programmes and reduced state welfare support placed heavier social and economic burdens on African women. Donor funding increasingly flowed through non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and redirected the efforts of women’s organisations from intellectual theorizations to social service delivery. Measurable ‘capacity-building’ projects were encouraged, which concretized workshops as a central feature of UN engagement. With the resulting rise of NGO-ization of African feminisms, the transformative ambitions of earlier pan-African feminist projects were neutralized.

Yet, the 1990s also saw the UN expand its entanglement in Africa’s civil wars, including the Somali civil war (1990-1995), the Rwandan Genocide (1993-1994), the First (1989-1997) and Second (1999-2003) Liberian civil wars, and the Sierra Leone civil war (1991-2002). The use of rape as a weapon of war shifted the UN’s agenda on women from gender equality to security. In response, the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations organized a seminar in Namibia on ‘Mainstreaming a Gender Perspective in Multidimensional Peace Support Operations’ in May 2000. The Windhoek Declaration was the outcome of this, which underscored the importance of women’s participation at all levels of peacekeeping, reconciliation and peace-building efforts as a measure towards gender equality in post-conflict reconstruction. This principle is the foundation of UN Security Council Resolution 1325, which was passed later in October of the same year.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

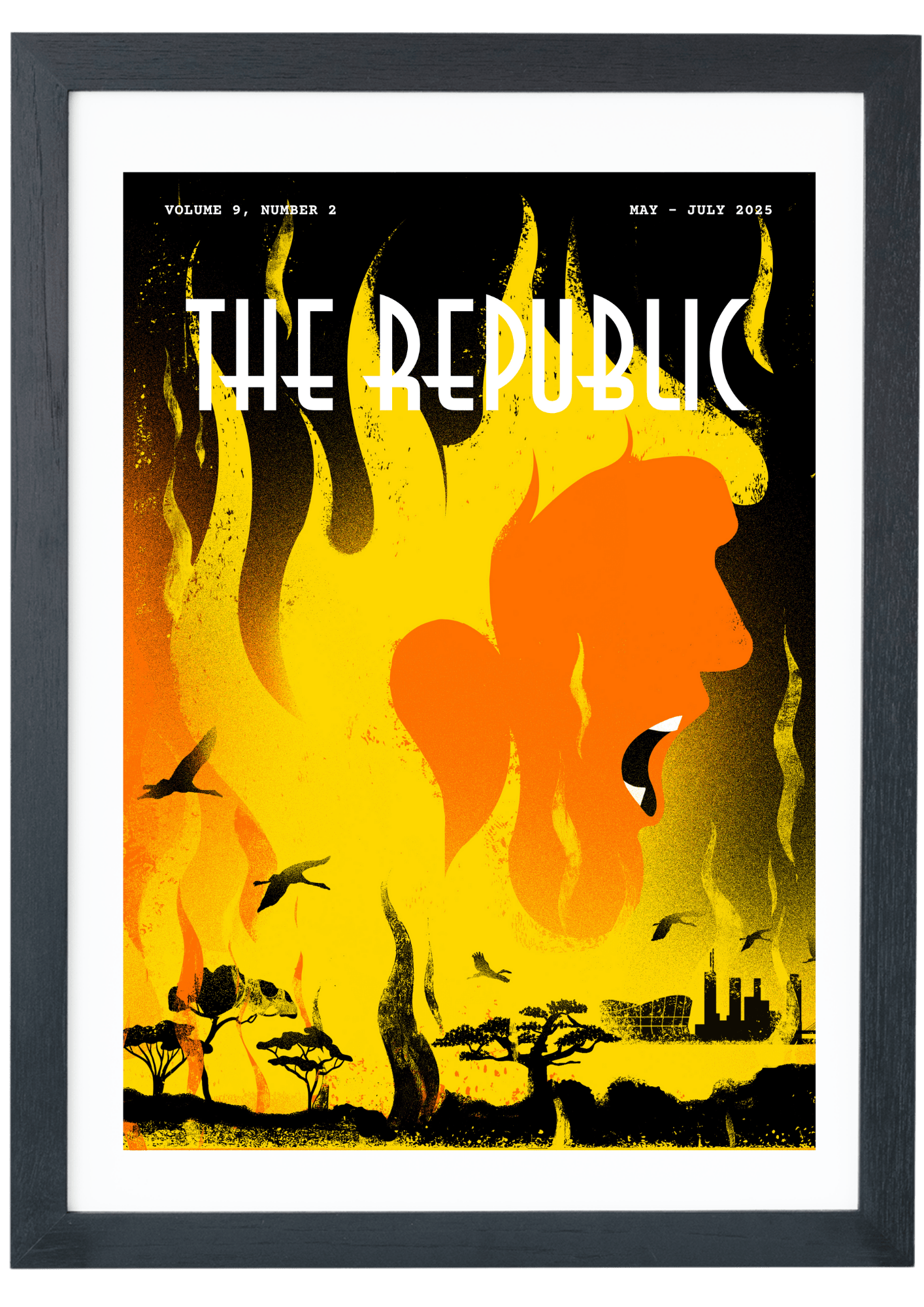

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00

DISCOURSE, INTERSECTIONALITY, AND SUBJECTIFICATION

This wasn’t unlike any of the other workshops I had been to. The sign-in sheet at the conference hall door welcomed participants into an air-conditioned conference hall where a white banner draped the speakers’ table. Concept notes and agendas lay evenly on round tables. UN representatives and government officials carefully handpicked for the opening and closing ceremonies waited to parrot multilateral lingo for the media cameras that would ensure prime-time coverage. The hotel snacks were standard. The transport refund promised at day’s end provided a quiet incentive.

When asked about the expectations for the session, a participant broke the polite rhythm as she answered, ‘Honestly, I have no expectations. We have been workshopped to death!’ The atmosphere immediately shifted. Her words protesting workshop fatigue contrasted the blue hue of her kitenge dress, which assimilated to the UN’s brand colours. Giggles were stifled and resonating heads nodded, as the donors’ faces flushed crimson. By tomorrow, the branded pens would be gone, but the ‘action plan’ would still detail the number of gender-mainstreaming trainings to be held as indicators of progress. As I observe the mixed reactions in the room, the corner of my eye catches the scribbled question on a young activist’s notebook: ‘If capacity can be built, can it also be dismantled?’

The ‘woman participant’ subject position in Africa, as articulated in the WPS agenda, is at once vulnerable (usually as a survivor of conflict-related violence) and competent (as a trainable peacebuilder). Policy technologies such as National Action Plans (NAPs), workshops, and monitoring indicators invite her presence while at the same time, scripting her behaviour. Her legitimacy is certified through inclusion in local peacebuilding expert rosters and through her mastery of donor vocabulary. The discursive effect is the active production of a governable subject whose agency is channelled into forms of participation that are legible to donors, without disturbing the underlying gendered, racialised, and classed hierarchies.

This is illustrated in the South African National Action Plan (NAP) 2020–2025, which features a policy stack of workshops, capacity-building curricula and log-frames, the logical framework models that structure interventions through predefined goals, indicators and assumptions. The NAP’s indicator-driven participation privileges those who can inhabit official venues and vocabularies, thus translating women’s presence into measurable outputs. This is further substantiated by a 2023 Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS) report, which found that NAP processes are often dominated by actors close to government or already well connected to donor networks. Civil society actors, especially those at the grassroots level or outside major urban centres, are frequently at the margins of implementation and monitoring. At the same time, indicator‐based metrics privilege presence in formal venues over substantive participation within the informal and everyday arenas where political life is actually negotiated. As feminist writer and scholar Sara Ahmed observes in ‘A Phenomenology of Whiteness’ (2007), when institutions are oriented around whiteness, even bodies that are not white must learn to inhabit whiteness. As a result, English‑speaking NGO professionals are celebrated as ‘competent participants,’ while grassroots activists are rendered invisible.

The UN workshop remains the most visible site of this production. UN engagements materialize most visibly in the carefully controlled settings of air-conditioned conference halls marked by registration desks, printed agendas, and branded banners. These spaces are carefully curated and choreographed to reinforce hierarchies of expertise. The hall thus becomes both a symbol and a conduit for the coloniality of power, staging women’s inclusion while delimiting their agency. The per-diem envelope functions as a consolation prize for the extraction of their knowledge, compensating participants just enough to assuage this exploitation. Meanwhile, the far more valuable product, the data, networks, and political legitimacy generated in the room, flows upward to funders and international agencies who depart with indicators of ‘success‘ and the authority to claim that local women’s voices have been heard.

Yet African women’s organizing has never been confined to these interiors. Open markets, village squares, and street protests remain vital arenas of African feminist politics. Only these spaces offer forms of gathering that are porous, unpredictable, and resistant to the logics of donor log-frames. From the white-T-shirt stylings of Liberian women’s mass action for peace to the Sudanese ‘woman in white’ leading chants of the revolution, street protests across the continent complicate any simple imperial demarcations between the ‘beholders’ and ‘owners’ of peace. Though markets and protests are not pure spaces of liberation, they too are entangled with histories of colonial policing and contemporary state surveillance. However, their openness allows for entry without invitation and encourages chorus responses. This creates possibilities for encounter and disruption that the conference hall is designed to contain.

In some cases, African women have leveraged the privileges of the conference hall to gain resources. Sierra Leone women leaders and the Ministry of Gender, for instance, used elite policy venues, legislative hearings, and coalition diplomacy to secure the 2022 Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Act. They turned conference diplomacy into enforceable quotas and budgetary levers for women’s participation and resources. Women’s rights organizations in South Sudan and Nigeria have also used WPS roundtables and donor consultations to argue for core, flexible ‘localization’ funds. These were later provided as unrestricted grants that groups used for their own priorities, thus shifting power from workshop-defined activities to locally directed agendas. These examples demonstrate that power can be reclaimed by repurposing tools imposed by dominant systems and engaging in alternative modes of participation that are unrestricted by universal policy frameworks.

shop the republic

THE CRISIS OF IMAGINATION AND THE POSSIBILITIES OF DECOLONIAL AFRICAN FEMINISM

Recently, the evolution of peace and security concerns and dynamics globally has brought the UN’s normative foundations and its operational capacity into scrutiny. Interconnected global challenges have led to a crisis of multilateralism. This includes the COVID-19 pandemic, escalating environmental degradation, climate change, persistent poverty and inequality, the erosion of democracy, rise in anti-gender rhetoric, the rapid advancement of digital technologies and their implications for privacy and social cohesion, impacts of population growth and migration and increased geopolitical competition.

In this conjuncture of systemic breakdown, the WPS agenda, once celebrated as a feminist breakthrough, has reached an ideological impasse. A crisis of imagination sits at the heart of global governance. We seem incapable of thinking beyond inclusion, participation, and empowerment, not because alternatives do not exist, but because they are actively foreclosed by the colonial architectures of power through which the UN operates.

Decolonial scholars, Sharon Stein and co-authors (2020) refer to this architecture as the ‘house of modernity’, a political order built on racial capitalism, extractive development, militarized security, and colonial dispossession. The WPS agenda, despite its emancipatory rhetoric, remains firmly located within this house. While it has engaged in soft reform, altering surface-level gender arrangements, it has often failed to confront the deeper epistemic and structural violence of the system. As African feminist scholar Amina Mama (2007) argues, global gender policy frameworks frequently domesticate feminist politics by translating power into technical programming categories such as capacity building, gender training, and participation metrics. By doing so, they strip feminist struggles of their political content.

This domestication operates through the discursive production of the ‘governable woman participant.’ She is simultaneously celebrated as evidence of global feminist progress and contained as a perpetual object of intervention. The WPS project does not dismantle this colonial subject; it merely updates her for the age of ‘inclusion,’ at least as dictated by the very same architecture producing her exclusion. To move beyond this framing, it is necessary to centre alternative subjectivities grounded in African women’s own histories of resistance, relationality, and survival. This shift requires what Professor of History, Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2018) calls epistemic freedom—the right of African peoples to define their realities and futures outside imported frameworks.

It is precisely here that decolonial feminist futurity becomes essential as both theory and method for displacing the present. It calls for a profound reorientation of how we think, feel, relate and organize politically. Such futurity rejects the illusion that global transformation can be achieved through institutional problem-solving alone. Instead, it seeks to unsettle the ontological and epistemic foundations of global security governance, demanding transformation not as reform but as the reimagining of worlds where being, knowing, and relating are no longer mediated by colonial logics of order.

Heidi Hudson, professor of International Relations, contributes to this rethinking by offering the framework of feminist frontiers—a conceptual and political space for decolonizing peacebuilding. She argues that the everyday must be treated as a legitimate site of theorization. Seen through this lens, our understanding of security can be drawn from the lived experiences of women and how they navigate and negotiate the violent entanglements of capitalism, patriarchy and militarism across markets, kinship networks, pastoral migration routes and customary justice processes.

Hudson’s approach also demands that we confront the material conditions that shape these lived realities. This means interrogating the socio-economic implications of establishing institutional infrastructures on foreign soil, including how the construction of military bases, UN field offices and NGO housing compounds reorders land use, distorts local economies, and reshapes power relations within the African continent. Such an interrogation reveals that security cannot be disentangled from questions of extraction, dispossession and spatial control. Most importantly, this perspective rejects the narrow fixation on the individual ‘woman participant’ as the primary unit of analysis. Instead, it turns our attention to the collective infrastructures of life-making that sustain communities, and to the political struggles required not only to defend them, but to transform the conditions under which life itself is made and secured.

Rather than offering a neat, ready-made alternative, which risks satisfying a colonial desire for certainty and technocratic absolutism, this framework emphasizes emergent, relational, and experimental practices of learning. It shifts attention to African feminist practices that already exist outside donor visibility: political economies of cross-border market women, the arbitration networks of grassroots peacebuilders, the digital organizing of feminist-queer collectives, and the matrifocal logics embedded in African restorative justice traditions. These frontiers foreground African women as world-builders, not workshop participants.

This approach is intersectional and insurgent. It affirms the thesis that African women do not lack power. What they lack are systems free from the colonial, capitalist, and militarized structures that distort their agency and reproduce their subordination. Decolonial, African, feminist futures, then, will not be realized through more toolkits, trainings, or policy harmonisation. They will emerge through projects that redistribute power, reclaim land, restore relational accountability, and refuse the coloniality of being.

shop the republic

FROM 1945 TO FUTURES BEYOND THE UN

The arc of African women’s engagement with the United Nations spans eight decades of creativity and critique. Excluded from the signing of the UN Charter in 1945, African women nevertheless forged early transnational connections and later consolidated their power through PAWO, influencing global policy on women’s rights, human security, and peace. Over time, they used the UN both as a platform for visibility and as an object of contestation, leveraging NAPs, workshops, and steering committees to gain resources while exposing the limits of donor-driven peacebuilding.

Yet the UN’s productive power lies precisely in its ability to shape the terms of women’s participation, while disciplining more radical demands for redistribution and self-determination. To recognize this power is to acknowledge how deeply the politics of inclusion are entangled with control. Moving beyond critique, therefore, requires imagination. It requires the envisioning of worlds where African women no longer need workshops, rosters, or per diems to claim agency, but where it emerges from the political infrastructures African women have always built.

Decolonial African feminist futurism offers both the commitment and methods for this work. It refuses the fantasy of reforming a faltering system from within, instead building on epistemic insurgency, ontological repair, and relational accountability. These futures embrace plurality, uncertainty, and experimental pathways toward liberation, grounding themselves not in conferences of global governance but in the markets, kinship networks and cross-border solidarities where African women have long negotiated power on their own terms.

As the UN marks its 80th anniversary, the task ahead is not another decade of reiterating the need for perfect inclusion, but to nurture the political life that renders the ‘empowerment’ category obsolete because African women already exercise power on their own terms⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N3 An African Manual for Debugging Empire

₦40,000.00

US$49.99