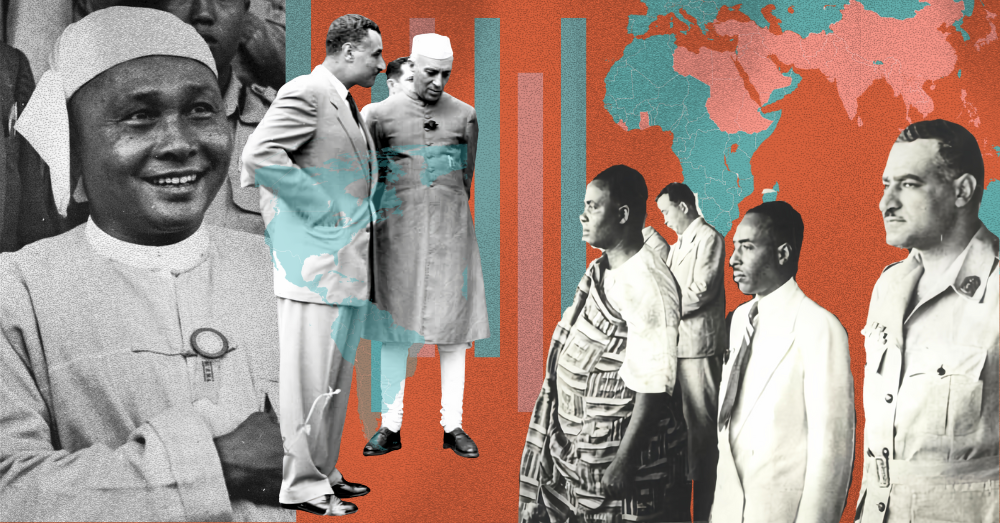

Photo Illustration by Ezinne Osueke / THE REPUBLIC.

THE MINISTRY OF WORLD AFFAIRS

After Bandung

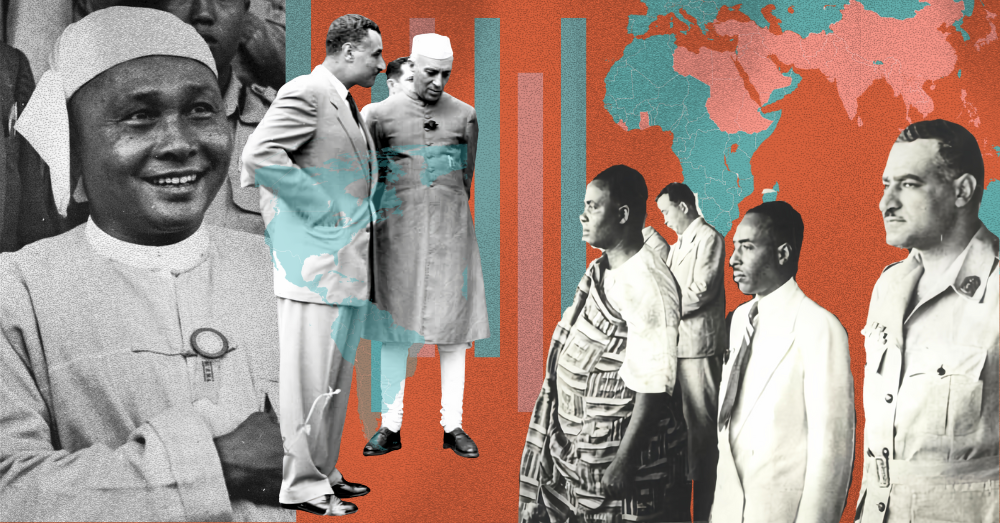

Photo Illustration by Ezinne Osueke / THE REPUBLIC.

THE MINISTRY OF WORLD AFFAIRS

After Bandung

Seventy years ago, in April 1955, newly independent countries from across Asia and Africa gathered in Bandung—the capital of the West Java province of Indonesia—to explore and assert their sovereignty, as well as to seek new development paths to enable economic and socio-political cooperation in the face of twentieth-century Cold War rivalries and imperialism. Apart from the main proponents of opposing ideologies—communism and capitalism—the ‘Cold War’ was anything but cold for the majority of countries in the ‘Global South’ (although the term denotes indirect hostilities, Global South countries quickly became proxy locations where ‘hot wars’ also took place extensively). It is in this context that the Bandung Conference was organized as a way to shake up international relations, and in the words of Indonesia’s then-president, Koesno Sosrodihardjo, mononymously known as President Sukarno, to ‘inject the voice of reason into world affairs.’

The significance of the Bandung Conference cannot be overstated, not least because at the time it occurred, the meeting represented 1.5 billion people—or about 54 per cent of the global population at the time. Its chief aim was to promote Afro-Asian cooperation. Another was to confront neocolonialism, structural economic inequity, underdevelopment, odious debt and other challenges obstructing the growth of ‘Global South’ countries. Although the geopolitical landscape has changed since the 1960s, the spirit of Bandung remains highly relevant today.

The 29 participating countries at the Asian-African conference in 1955 proposed several principles to serve as a foundation for ensuring cooperation and commitment to shared development among nations. Of the ten adopted principles, two stand out in relation to today’s geopolitical context. The first is the committed adherence to the United Nations Charter of 1945, with a focus on respecting human rights and the sovereignty of nations. The second is the abstention from intervention in the internal affairs of other countries.

Although the geopolitical landscape has in many ways changed since 1955, the problems that highlighted the need for an initiative like Bandung remain. Many countries, especially of the ‘Global South’, still face concerns of economic disparity, power imbalances and great-power rivalries unduly influencing the fate of many nations.

In recent years, initiatives like the international organization, BRICS, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and the African-led push for reforms in global finance are indicative of ‘developing’ countries seeking structural changes to international relations. It is also reflective of the ideals of Bandung, rooted in economic cooperation and the reduction of dependence on colonial countries. Additionally, cooperation between ‘Global South’ countries has seen great spikes in global trade, skills transfers and diplomacy. Institutions like the African Union (AU) and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CARICOM) embody the principles of regional cooperation as promoted in the Bandung vision—but there is much to be desired as per the effectiveness of the AU, for example.

Although these groups signal a move away from passivity in global politics, new challenges have emerged. For instance, multilateralism is a key value in the Bandung spirit. But we can also easily observe international institutions being undermined by geopolitical power plays and great-power rivalries, which in turn have led to a fragmented global order. From trade wars to rampant sanctions and dubious military interventions, the principles of non-interference and cooperation are either disregarded or actively undermined.

My overarching point is that countries of the ‘Global South’ are asserting themselves by seeking mutual respect, commitment to cooperation, shared development, and a vision for global governance that upholds the principles of the Bandung Conference as opposed to domination and cynical realpolitik. Since the conference was held in 1955, the need for shared growth and prosperity for humanity and not a privileged few remains the wise course of global governance and international relations.

AFRICA-ASIA ECONOMICS RECHARGED: BANDUNG STYLE OR STRICTLY BUSINESS?

Afro-Asian relations have recently experienced a resurgence. In the context of the Bandung Conference, this resurgence is not overtly ideological, but commercial, which is what colours regional politics, diplomacy and bilateral relations. Trade between China and African countries, for example, is now led mostly by demand for rare earth minerals, crude oil and diverse agricultural products. Another example is Malaysia promoting trade with Uganda, while reports show that there are more than 2,000 Vietnamese agronomists training and working with farmers in Benin, Senegal, Madagascar and Congo-Brazzaville.

In 2024, India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, visited Nigeria with the aim of strengthening bilateral ties. Nigeria is India’s second-largest trading partner in Africa, with bilateral trade reaching a high of $11.8 billion in 2023. With over 200 Indian companies currently operating in Nigeria, Indian companies are among the largest employers in Nigeria, second to the federal government. Casting a wider view on Nigeria-India relations, we can see that the focus is on spreading investments across sectors such as transportation, infrastructure, maritime security, mining and textiles. The point, as stated earlier, is that motivations to cooperation are no longer guided by liberation ideology or anti-imperial perspectives. Many governments that formerly participated in the Bandung Conference now prioritize trade, investment and diplomacy.

Contemporary ‘Global South’ relations, especially at the government-to-government level, are mostly ‘business-focused’. With this point, it is easy to see how the BRICS initiative provides a counter-balance through the promotion of alternative cooperation models and geopolitical self-determination. With an eye to building an equitable global system, African and Asian countries should be able to reshape global governance and economic structures in a way that encourages South-South countries not to be subjected to the whims of governments that have benefited from age-old power structures established through colonization and imperialism.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00

CONTEMPORARY GEOPOLITICS—WHERE IS THE BANDUNG SPIRIT?

The Bandung Conference brought in a new era of ‘Global South’ cooperation. This momentum persists today, with groups like the AU, CARICOM and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. These groups not only provide platforms to foster deeper integration and solidarity, but also the potential for a fairer global economic system. At the forefront of this push are groups like BRICS—and within this context, the role China has played has been vital. As a leading economy on the global stage, China has effectively become a top economic and geopolitical alternative partner that many countries have pivoted to when seeking assistance to achieve development goals. The BRI is a useful case study showing how the expansion of connectivity has led to the generation of economic opportunities across partner nations.

With the aim of reforming the international order that has short-changed African, Asian and South American countries for so long, the communique from the conference was simply an indictment of a global order that often ignored the historical and social realities of colonized peoples, placing focus mainly on inaccurate representations of progress—especially within dominant societies of the time.

As the Cold War raged on through the 1950s, countries that participated in the Bandung Conference sought a third way by prioritizing neutrality in the face of ideological struggle between capitalist liberalism led by the US and its allies, and communism led by the Soviet Union and its allies on the opposing side. The decision to collectively seek a third way can be seen as the start of the journey towards a multipolar world order—an era currently being ushered in as more countries move away from the unipolar order that was established from the 1970s with US leadership. This third way is referred to as the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Since 1955, NAM has had 120 member nations—all of which are from the so-called ‘Global South’. Every African country, moreover, is a member of NAM—with South Sudan gaining admission to the movement in January 2024 following the 19th Summit of Heads of State and Government of NAM that took place in Uganda.

shop the republic

Considering that NAM and the Bandung Conference are products of the Cold War era and the wave of independence struggles, much evolution that has taken place, especially as global governance is becoming increasingly multipolar. As a result, countries of the ‘Global South’ are often switching diplomatic alignments to favour collective development and shared growth paths.

From the nineteenth-century imperialist scramble for Africa, to the ravages of the ‘Cold War’ during the 20th century, African nations have caught on and recognized this present era as one of proactive diplomacy, dynamic relations and intentional cooperation. These factors call for versatile policymakers and effective governance. Countries of the ‘Global North’—still in the habit of paternalism—view proactive changes and drives for self-determination in Africa as ill-fated pursuits, leading individuals like the commander of US Africa Command, General Michael Langley, to berate Burkina Faso’s president, Captain Ibrahim Traore, for not prioritizing the fight against terrorism—ignoring the facts on the ground in Burkina Faso, such as popular support from the people for the changes in mode of governance and socioeconomic policies.

This brings into focus the Alliance of Sahel States (Alliance des États du Sahel; AES)—a newly formed group that has effectively overturned the geopolitical status quo, especially in western Africa. Following the spate of coups that took place from 2019 until 2023, Burkina Faso, along with Niger and Mali, saw massive government upheavals that swept away the tradition of civilian politicians and bureaucrats in government, bringing in the military instead. While coups are not uncommon occurrences in African countries, the difference this time was the character of the ruling juntas in these countries. This time, there was much popular support from the citizenry, who had grown frustrated with the incompetence of the former ruling powers. Moreover, the decisive manner through which the junta made productive changes in education, agriculture and security also demonstrated to the populace a political will that has been long absent in Africa as a whole.

Niger and Mali have evicted the French military from their respective territories—effectively ending all military engagements between them and an imperial power—while Burkina Faso and Niger have nationalized their gold and uranium, respectively, as strategic resources. Without surprise, this has put the Euro-American bloc in somewhat of a tailspin because the long-established traditions of neocolonialism are being broken in real-time. This is exposing the fractures within the European Union, for example, where the US-backed proxy war against Russia has resulted in the loss of the Nord Stream gas pipeline that supplied cheap gas to European households. This has left politicians and policymakers either scrambling for energy source alternatives in northern African countries such as Morocco and Algeria, or looking to the US for the far more expensive Liquefied Natural Gas. The point here is that there is a major disconnect between the development priorities of Europe and Africa. While Europe has its own security concerns, with a focus on migration and stability of energy supply lines, African countries are seeking alternative partnerships to confront issues around jump-starting their economies while taking larger roles in diplomatic and geopolitical frameworks such as the BRI, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), and the Global Development Initiative.

Like many countries of the ‘Global South’, African nations have little incentive to staunchly align with any global powers, and it is evident that these complex relations are being managed while aiming to find a strategic sweet spot that affords partner countries the benefits of shared development and balanced cooperation—‘win-win scenarios’ as promoted by China. Interestingly, countries of the ‘Global South’ are becoming more effective in maintaining their non-aligned stance while engaging partnerships apparently set up by rivals, essentially walking a diplomatic tightrope of sorts. An instance is South Africa, which has been a participant in the US’s African Growth and Opportunity Act, while being a founding member of BRICS, with Chinese and Russian critical security partners even conducting naval exercises with them in 2023. The year 2022 also saw many African countries refuse to adopt the Euro-Atlantic bloc’s stance on sanctioning Russia in its special military operation in Ukraine, going to show that in its basic form, the spirit of non-alignment as promoted at Bandung is alive.

The counter to these findings, however, is that while African nations have moved to condemn the paternalistic and neocolonial tendencies of global economic policies, there is still a dependence on the structures and institutions that brought forth these policies. African nations and many other ‘Global South’ countries still find themselves hostage to factors like unequal exchange, odious debt, and security dependence. Unfortunately, these facts have led many countries of the ‘Global South’ to compromise on principles of the Bandung spirit.

shop the republic

A REVIVAL WILL BE WORTH IT

Looking at the major influences on the global stage, it stands to reason that countries of the ‘Global South’ would benefit from a material resurgence of the Bandung spirit—even in the form of an actual conference that doesn’t just reflect on the 1955 event, but looks forward to the future, establishing itself as an update: a refresh, or recommitment to the principles promoted in the original conference. This is because an initiative like BRICS that initially focused on trade, investment and South-South cooperation, rightly so, has now introduced the mission of economic independence—and multipolarity as opposed to unipolarity. This is further observed in the BRI, which has seen China maintain 46.6 per cent of its total trade exclusively with countries within the BRI network. Although the BRI has had its own ups and downs, its impact on the global economy signals a major shift in trading preferences, considering the fact that China is a major trading partner with more than 120 countries, according to 2021 data provided by the UN Conference on Trade and Development.

The challenge today, however, is that only a handful of countries actively hold these progressive stances as expressed in the Bandung Conference. In this context, there is a combination of frustration with neoliberalism, activated people’s movements, and the political will to break from neocolonial modes of international relations. There are cases like Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua in South America, the AES in Africa’s Sahel, and China, Russia and Vietnam in Asia that reflect this argument. A 2025 research at the Tricontinental Institute of Social Research suggests that, standing in the way of the resurgence of a new Bandung spirit, is the looming threat of hyper imperialism, which states that the only true political-economic-military bloc in the world is the US-led alliance of NATO and the State of Israel. This is because even though there is a move away from US-led unipolarity and a decline in imperialist economic and technological power, this bloc still has massive military capabilities and holds deep control over the global information system. We observe the ferocity with which hybrid warfare and the threat or use of violence are levelled against nations seeking sovereignty in the slightest. This reality requires a collective or unified response from the ‘Global South’ that may take the form of a renewed Bandung spirit.

For the Bandung spirit to effectively bloom, it is critical that nations of the ‘Global South’ confront the contradictions that limit a coming-together of like minds in this era of hyper-imperialism. These contradictions include but are not limited to: the simultaneous fear and desire for Euro-American leadership on the global stage regardless of the many failures; the surrender to imperialist control of digital media and financial technologies of the sector as a whole; and the fact that the majority of the ruling elite within the ‘Global South’ are still deeply linked to global financial capital as reflected in the dependence on the US dollar—as they participate in wealth extraction from their own countries to invest in the ‘Global North’. Conversely, in the African context, the AfCFTA is an apparent example of high-quality policy, where if properly and effectively implemented, intra-African trade will be boosted and cross-border movements will be greatly improved for Africans themselves, not just in finance or goods.

It is of the utmost importance that the people of the ‘Global South’ overcome these challenges if the ‘Bandung spirit’ is to be rekindled. The legacy of the Bandung Conference is certainly alive and well—but we of the ‘Global South’ must hold steady the course of justice that can breed a popular capture of state power with the aim of establishing people-centred governments where modes of production serve collective growth and dignity⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N3 An African Manual for Debugging Empire

₦40,000.00

US$49.99