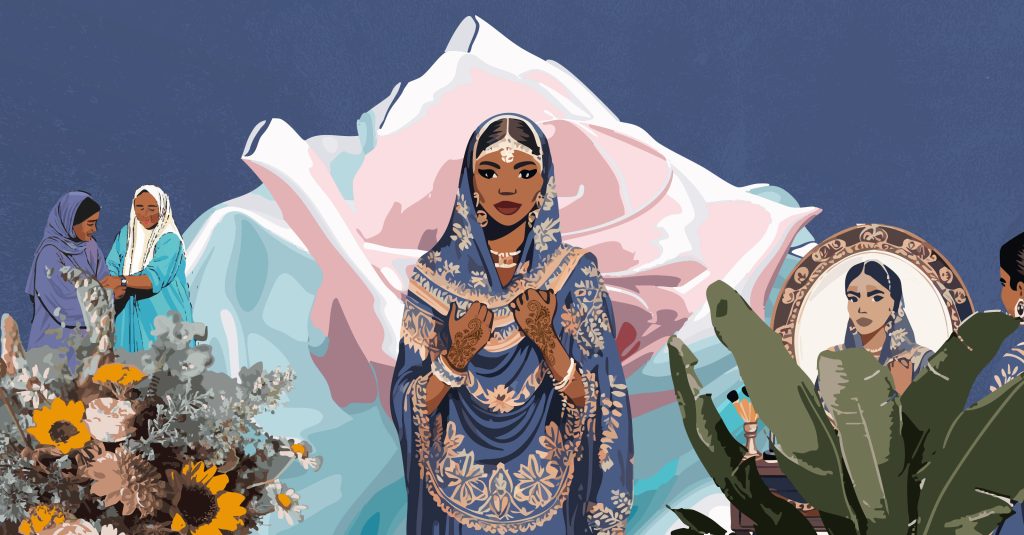

Photo illustration by Michael Emono / THE REPUBLIC.

THE MINISTRY OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS

How a Flowing Veil Shaped My Identity

Photo illustration by Michael Emono / THE REPUBLIC.

THE MINISTRY OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS

How a Flowing Veil Shaped My Identity

I was twelve when I first fell in love with a piece of fabric—the laffaya. Five yards of soft, patterned cloth, draped across my shoulders and wrapped around my body, made me feel more like myself than anything else in my wardrobe. It wasn’t just clothing. It was identity. Comfort. Quiet confidence.

THE LANGUAGE OF A PIECE OF CLOTHING

In northern Nigeria, especially among Arewa women, the laffaya or mehlfa carries symbolic meaning that shifts with context. For Hausa-Fulani women, the laffaya—wrapped as a skirt and draped over the shoulders like a hijab, paired with a blouse—is both a bold fashion choice and a quiet badge of modesty, while the mehlfa, nearly identical to its Sudanese cousin—wrapped under the arms and knotted around the chest before being draped over the head as a veil—becomes a whispered announcement of religious devotion for those who use it as their hijab and a reminder of how it was the only appropriate and affordable covering for them.

In Arewa, bridal laffaya shimmers with elaborate embroidery and metallic threads, while everyday wear is made of soft, simple cotton or cheap chiffon. There are rules, unspoken but heard. The intricate, heavy patterns belong to wealthy older matriarchs, the lighter touches to young women or bridesmaids, but each fabric hints at status, family ties and the quiet pride of an Arewa woman who wants her clothing to speak before she does. The night before an important event, she perfumes the cloth with turaren wuta—a northern incense blend of sandalwood and resin—folds it delicately and chooses accessories that are just enough to show her status: not too much, but especially not too little. The ritual and intention begin before the fabric ever touches her skin.

Long before the Arewa woman draped this cloth over her body, pieces of it (not quite similar, not yet coined as the mehlfa or toub) were worn elsewhere. Two locations are considered the homelands of the Toub: the River Nile valley, dating back over 10,000 years to the Sudanese Bagrawiya civilization and the historic port of Suakin in eastern Sudan. Women take particular pride in the belief that al-toub was the national costume of queens and that Queen Kandake was the first to wear it. However, no records show that it was called al-toub or mehlfa.

In Arabic, the word ‘toub’, sometimes known as ‘thawb’, refers to clothing in general, but for Sudanese women, it refers to an outer garment of 4.5 meters draped over their bodies, a social status symbol for them, with various attributes of the toub denoting wealth and refinement.

Additionally, the toub is the most resilient aspect of the national costume worn by Sudanese women. Its beauty and versatility have made it endure, while other costumes like the rahat and gurgab have vanished. A rural woman’s toub may serve as her nightgown, mosquito net, outerwear or curtain behind which she can nurse her infant in public. It may also be used as a pouch for collecting cotton or other crops.

In the nineteenth century, the Mahdi reform movement banned ‘Turkish’ fashion and ordered that all women wear veils to conceal their faces in public. Prior to this, and even now, only the women of the Rashaida tribe wore the ginaa—a unique, elaborately adorned veil. The Mahdiya women, without a ginaa, secured their toubs over their faces by pulling the jedaa, which is the end of the toub that is typically thrown over the shoulder, securely across their lower faces. The remaining yard or so was then draped over their heads.

The mehlfa or toub or laffayah goes by many names. While its earliest appearance is said—though debatably—to have originated in Sudan, it has been adapted across Sahelian cultures through trans-Saharan trade, gaining unique significance in each. In Mauritania and Mali, the clothing is referred to as dampé or mehlfa, while in northern Nigeria (Arewa), Niger and Chad, it is known as laffaya. In Sudan, it is commonly called tiyyab or toub, fūṭa in eastern Sudan, and al lāwu among the Shuluk tribe. From Chad to Eritrea, Ethiopia to Djibouti, Somalia to Mali, the Nubians of Egypt and across North Africa in Morocco and Algeria, the laffaya has been adopted by diverse cultures.

The toub does not just have different names across regions, Sudanese women were witty and smart with it. They coined new names for each toub style, reflecting political climate, social trends and even popular love songs of the time. One of my favourites is Lahalibu (meaning ‘Flames’), a coloured toub from the 1950s and 1960s covered in large acrylic squares. These toubs perfectly matched the Arabic rhyme: ‘لحليبو – لو قادر جيبو، لو ما قادر سيبو (Lahalibu – law qadir jibu, law ma qadir sibu)’, ‘Whoever can get it, so—Who cannot, let it go.’ Another is Khartoum bil layl (‘Khartoum by Night’), a perfumed, glittery black toub inspired by the city’s aerial views after dark.

Then there is Al budrah (‘Powder’), Al sawdanah (‘Sudanization’), Wad al siyufi (‘Son of the Sword’), Zahrat al khalij (‘Flower of the Gulf’), Afrah al qulub (‘Joys of the Heart’) and Al ghirah (‘Jealousy’)—a yellow coloured toub.

I remember pausing at a comment on Pinterest that read, ‘This is a Toub.’ It referred to a photo of a woman dressed in what I had assumed was a laffaya, ‘a Sudanese cultural attire,’ the comment explained. I raised my eyebrows, slightly confused. Yes, the wrap was familiar—but different too. It was more sculptural, wrapped fully around the chest and torso in soft loops, the cloth flowing like a robe. As I watched more videos and pictures of Sudanese women in this attire, I noticed how they styled it differently: they wore jewellery on their heads, around their necks and sometimes even on their waists. The adornment was part of the language. Rings stacked on fingers, bracelets jingling at wrists, and just like in the traditions I knew, there was incense burning thickly around her as she sang, the smoke rising like a veil of its own.

What truly shifted something in me was a cover art by Aya Mohamed—a soft sketch of a Sudanese woman holding flowers. Around her, other women gathered, all wrapped in what I had always known as the laffaya. They circled her gently, their bodies moving in quiet rhythm, faces turned away as she stood at the centre, facing the viewer. The image was powerful, and the title stirred something painful in me. That image stayed with me. I finally understood that this cloth wasn’t tied to one place or one people or even one meaning. It was a shared garment. A shared memory. A symbol of strength. A garment whose meaning travelled with the women who wore it—adapted and reinterpreted but never lost.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00

LEARNING THE RITUALS

Growing up in northern Nigeria, modest dressing wasn’t simply expected; it was embedded in the rhythms of daily life. The laffaya, with its graceful sweep and soft drape, seemed to speak directly to my nature. Its flowery patterns, range of colours and the gentle way it moved with me made me feel like a princess in a carriage—protected, poised and held. It quietly matched my reserved personality. I didn’t have to speak loudly to be seen.

The first time I saw a laffaya was on my sister. The first time I wore one was because of her. She gifted me a cloth of maroon and burnt orange, its colours shifting across the fabric like dunes at sunset. I remember wearing it for my school’s cultural day. Though I felt shy at first, I wore it with pride. I stood in front of my mirror and folded the cloth the way she’d taught me. I stepped into school that day, unsure of how people would react. Not many students recognized the garment. But when the questions came—‘What is it?’ ‘Where’s it from?’—I answered with pride. I told them it was called a laffaya, worn by Shuwa Arab women. I felt like a translator of culture. I felt seen.

While my sister had introduced me to the fabric, my mother was the one who taught me how to wear it with dignity. She had learnt from a friend from Chad and passed that ritual to me. I remember the way she folded the ends, showed me how to let it fall lightly over one shoulder, and how to carry myself with it—never hurried, never flustered. There’s a walk that comes with the laffaya: not slow, but certain. Not forced, but full of pride. Later, I found myself passing it on, teaching my aunt how to wear it for her wedding because she admired how I styled mine. That’s the thing about cultural dress: it lives in how we share it.

In that moment with my aunt, I felt like a queen mother dressing her daughter, the princess, for her coronation. There was something sacred about it. I wasn’t just wrapping cloth around her; I was showing her how to shine in it. How to make the fabric crown her, not just cover her. It was her day, and I wanted her to feel it in every fold. The laffaya had to speak before she even said a word.

We practised for hours. I showed her how to tie the edge and tilt the wrap so it framed her face. The material rustled as we moved, soft and fragrant with turaren wuta. At one point, she stopped me—gently, confidently—and began tying it herself. A small, quiet moment, but it said everything: she had learnt. She had claimed it.

The laffaya is elegant, yes, but it is also instructive. It teaches you how to move, how to hold your head high. You don’t just wear it—you become it. There is a sensuality in the way it wraps the body, not in the Western sense, but in the quiet power it gives. It feels like wearing jewellery that moves with you. You don’t disappear beneath the cloth—you emerge, more refined. The laffaya gives the illusion of softness, but you walk in it with sureness, with a sense of knowing. It doesn’t drown you; it defines you.

There is a misconception that the Laffaya restricts you, that the knotting of the skirt and draping almost rolls you into a ball of fabrics, but I’d argue the opposite. It teaches you control. In wearing it, you understand how much space you take, how to move with grace, and how to speak through style. It can completely conceal the woman and hide the outline of her body as well as her identity. So, when older women see a young woman wearing the laffaya today, it signals something unspoken: that she is thoughtful, firm and rooted in her identity.

shop the republic

EID MORNING: A SACRED CHOICE

It was the day after Eid—the ‘outing day’, as we called it in my local community. My sisters and I had been planning for weeks. We were going to wear our new laffayas—a gift from a close friend who had travelled during the holiday and returned with fabric and perfume for each of us. That gesture alone—a friend thinking of us while far away—made the cloth feel special before we even touched it.

When the laffayas arrived, we gathered around with laughter, excitement rippling through the house. Mine was hot pink chiffon layered with baby pink and red polka dots, streaked with gold glitter that stuck to my skin like stardust. I loved how the shimmer clung to my arms and neck. My sister received the soft pink one with circular overlays, delicate and playful. And my other sister wore a laffaya in gentle green with blooming floral patterns.

That morning, I chose a set of carved red-stone jewellery to match mine. Gold bangles slid onto my wrists, chiming softly as I moved. My henna was fresh and I had curled my hair the night before, packing it sleekly in place. I don’t usually dress up; fashion has always lived for me in writing, in the shows I admire and in the countless magazines and journals I read. But the laffaya brings something forward in me. It revives me. It is a way to stand fully in who I am. And that Eid, I needed that reminder.

shop the republic

THE WEIGHT AND THE WANT

The months before had been hard.

Burnout had crept into my days like a slow fog—thick, invisible and impossible to shake. I didn’t notice it at first. But soon, everything I once did with joy began to feel heavy. I was uncertain about my career, unsure what direction to take or even what ‘right’ meant anymore. The certainty I had once carried—the version of me that was prepared, composed and clear-eyed—felt like someone I used to know.

The burnout didn’t just make me tired. It made me question everything. It felt like logs of wood stacked across my shoulders, pressing down until my posture collapsed inward.

And then came the pressure—to meet up, to catch up, to succeed visibly. To turn every interest into content. But all I felt was numbness. I couldn’t summon joy for any project or idea, even the ones I’d once dreamt of. Growth, failure, trying—it all felt distant. I grieved the girl who had certainty. Who felt joy without guilt. Who moved through her life with confidence and familiar faces around her.

So, when I stood in front of the mirror that outing day—henna on my hands, glitter on my skin, laffaya soft and perfumed against my body—it wasn’t just dressing up. It was a quiet reclaiming. I am still here. Maybe not certain. Maybe not lit up with clarity. But still here. Still trying. Still wrapping myself in beauty, even when I feel empty. In that cloth, I remembered how it feels to stand tall. How to see myself again.

As we walked into my aunt’s home, on the edge of the city, surrounded by trees and dry winds, greeted with hugs and warm Eid wishes, I felt held. Not just by my laffaya, but by the meaning I had stitched into it. It wasn’t just a look. It was a declaration: I am still here. Still beautiful. Still me⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N3 An African Manual for Debugging Empire

₦40,000.00

US$49.99