Photo Illustration by Michael Emono / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref: Akintunde Akinleye / REUTERS.

THE MINISTRY OF BUSINESS X THE ECONOMY

What Naira Decoupling Means for Nigeria’s Economy

Photo Illustration by Michael Emono / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref: Akintunde Akinleye / REUTERS.

THE MINISTRY OF BUSINESS X THE ECONOMY

What Naira Decoupling Means for Nigeria’s Economy

Nigerians have long endured several volatile macroeconomic environments since independence in 1960. From staggeringly rising exchange rates, alarming inflation levels, high unemployment, to an economy whose performance has been tethered to oil since its discovery in Oloibiri in 1956. We have grown so accustomed to several harsh episodes of volatility that any positive development in the economy sounds like propaganda met with public criticism, mockery, and mixed reactions. Thus, recent analysis on the naira’s upward trajectory was dismissed as unsustainable and premature.

On 8th July 2025, Anthony Osae-Brown, bureau chief at Bloomberg Africa, and Bloomberg analyst Emele Onu co-authored a viral article revealing a striking development in Nigeria’s currency markets. Little did they know their report would ignite a firestorm of debate. The article highlighted that, over the last four quarters, the naira’s movements seem increasingly independent of crude oil, a phenomenon now called naira decoupling.

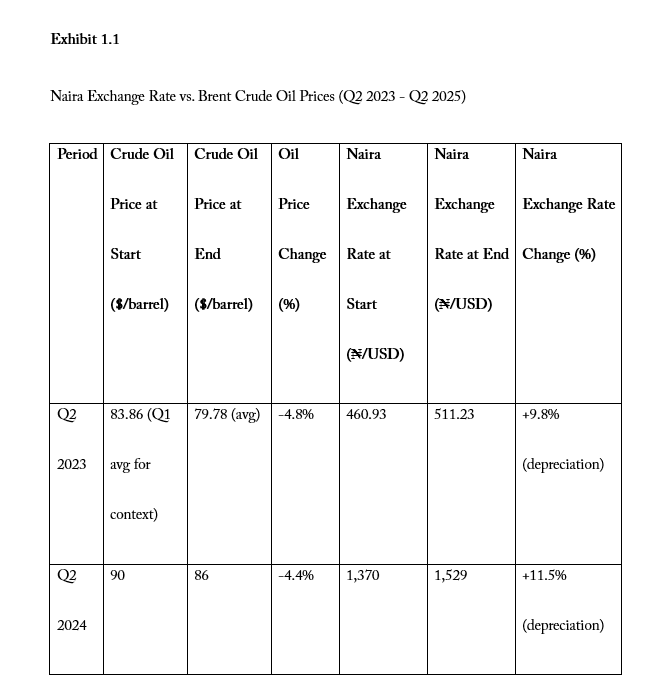

As a resource-rich country, Nigeria’s currency performance has historically mirrored the movement of oil prices. When oil prices rise, Nigeria earns more dollars from crude sales, and the naira tends to strengthen. When oil prices fall, fewer dollars flow in, and the naira weakens. Evidence from the 2023 Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) second-quarter report shows the relationship clearly. In Q2 2023, the average exchange rate of the naira to the dollar at the Nigerian Foreign Exchange Market (NFEM), previously the Investors & Exporters Window, depreciated by 9.8 per cent, from ₦460.93 to $1 in Q1 2023 to ₦511.23 in Q2 2023. During the same period, Brent crude averaged $79.78 per barrel, down from $83.86 in Q1 2023, showing the classic naira-oil correlation. The trend persisted in 2024. In Q2 2024, Brent crude traded between $86 and $90 per barrel while the naira fluctuated between ₦1,370 and ₦1,529 per dollar.

However, 2025 tells a different story. At the beginning of Q1 2025, Brent crude traded at $76 per barrel, falling to $69 by early March. Despite this decline, the naira appreciated, moving from ₦1,631.40 to ₦1,493 per dollar, ending the quarter at ₦1,532.80. This pattern contrasts sharply with past trends, where the naira’s value mirrored the fluctuations in oil prices.

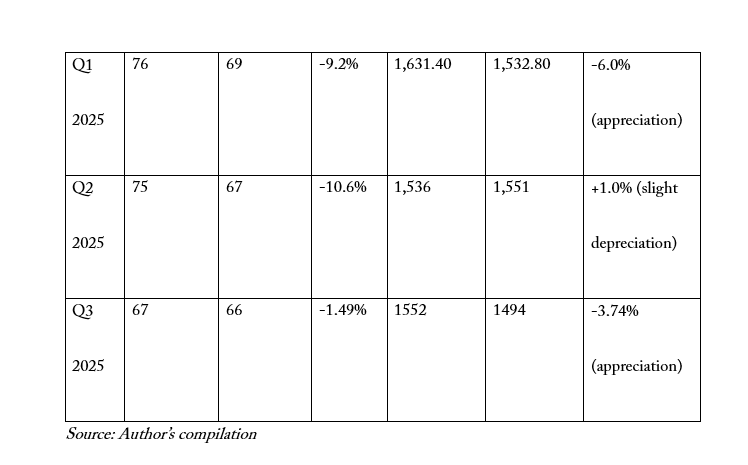

A similar deviation from the norm occurred in Q2 2025. Brent crude began the quarter at $75 per barrel and fell to $67 by the end of the quarter, a 10.6 per cent decline. Yet, the naira remained relatively stable, trading between ₦1,536 and ₦1,551 per dollar. Q3 2025 showed similar stability, with Brent crude opening the quarter at $67 per barrel and trading at $66 by the end of the quarter. Naira to the dollar exchange rates held steady at ₦1,552 and ₦1,494 at the beginning and end of Q3 2025, respectively. This relative appreciation of the exchange rate, despite notable drops in oil prices, signals the onset of naira decoupling, a divergence from the usual naira-to-oil dependency.

The Exhibit below highlights the decoupling trend in 2025, where naira stability persists despite falling oil prices.

Notes:

Oil prices reflect Brent crude, with Q2 2023 using quarterly averages

Naira exchange rates are from NFEM and the Wise Currency website

Brent Crude oil prices are from Trading View.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00

UNDERSTANDING NAIRA DECOUPLING

In economics, decoupling happens when different economic variables that typically rise and fall together start to move in opposite directions, such as one increasing while the other is decreasing and vice versa. In the case of the Nigerian economy, there has always existed a correlation between Brent crude prices and the naira exchange rate to the dollar. Naira decoupling would happen when the naira exchange rate diverges from its expected or normal correlation with the rise or fall in crude oil prices. We have seen this play out in the last two quarters of 2025, which is an interesting turn from historical movements.

For decades, Nigeria’s economy has lived under the shadow of oil since it was first discovered in Oloibiri in present-day Bayelsa State in 1956. Oil accounts for roughly two-thirds of Nigeria’s government revenue and about 90 per cent of its export earnings. As a result, the naira has traditionally been tightly tethered to oil performance: when oil exports boomed, foreign reserves grew, the naira gained stability, and fiscal policy was expansionary. Conversely, oil price crashes, as seen in 2014–2016 and during the COVID-19 pandemic, triggered rapid devaluations, fiscal austerity, and inflationary spirals.

This dependency created what economists often call a commodity currency. This is a phenomenon where a currency’s strength is disproportionately dictated by global commodity markets rather than domestic productivity. In Nigeria’s case, the relationship became almost deterministic: oil prices served as a proxy indicator of naira stability. For instance, in mid-2014, Brent crude averaged $110 per barrel, and the naira traded steadily at about ₦165 to the dollar. However, by early 2016, with a managed floating exchange rate, when crude prices collapsed below $30 per barrel, pressure on the naira mounted, with the parallel market exceeding ₦300 to the dollar while the official exchange rate remained pegged at ₦197. In June 2016, the CBN abandoned the exchange rate peg, and by late 2016, the official exchange rate had depreciated to around ₦305, while the parallel market spiralled beyond ₦500.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed a similar vulnerability. In April 2020, oil prices briefly turned negative in global markets before stabilizing around $40 per barrel. Nigeria’s oil revenues collapsed by over 65 per cent year-on-year. Foreign reserves fell below $35 billion. The CBN was compelled to devalue the naira twice in one year at the official Investor and Exporters (IE) window to ₦380 in August 2020, after an initial adjustment from ₦306 to ₦360 in March 2020. By the end of December 2020, the exchange rate at the IE window had depreciated further to ₦410.25. Inflation accelerated to over 15 per cent, an increase from the 11.98 per cent rate recorded in December 2019, eroding household purchasing power—accentuating how oil-linked currency instability filters into broader macroeconomic fragility.

The CBN’s policy manoeuvres further entrenched this oil dependency cycle. In periods of high oil prices, such as 2011–2013, when crude averaged above $100 per barrel, the apex monetary authority could defend the naira aggressively, drawing on reserves that rose to about $44 billion. However, in downturns such as 2015–2016, reserves plummeted to around $28 billion, making such defence increasingly unsustainable and fuelling sharp devaluations.

The reliance on the oil boom and bust cycles to regulate the macroeconomy came at a cost. A 2023 analysis in the CBN Journal of Applied Statistics noted that oil price volatility remains the single biggest source of macroeconomic instability in Nigeria, while researchers at Babcock University, Nigeria, have argued that this dependence has weakened incentives for diversification. The predictable oil–naira correlation discouraged long-term industrial policy, incentivized rent-seeking, and left Nigeria dangerously exposed to external shocks. Additionally, it normalized a fiscal model where budgets were benchmarked against oil price projections (as is still the case today) rather than grounded in diversified revenue sources. As a result, instead of acting as a stabilizer, oil revenues became a destabilizing force, fuelling expansion during booms and austerity during busts, with the naira at the centre of the volatility.

In mid-2025, Bloomberg reported that the naira remained stable at around ₦1,530 to the dollar, even as oil prices weakened, signalling a surprising divergence from historical trends. Analysts from Deutsche Bank, CardinalStone, and Standard Chartered attributed this resilience to reforms such as foreign exchange (FX) market liberalization, higher non-oil exports, improved investor confidence, and fiscal discipline. This phenomenon, where the naira no longer mirrors crude oil swings, marks the beginning of naira decoupling.

What does this instantly signal in the economy? This shift reflects a transition from commodity-dependent macroeconomic management toward a more diversified and reform-driven exchange rate framework. The Central Bank’s liberalization of FX markets reduced speculative pressures that once amplified oil-price shocks. At the same time, a steady rise in non-oil exports, especially agricultural commodities and manufactured goods, has begun to provide alternative streams of foreign exchange. This combination has altered the elasticity of the naira to oil fluctuations. Whereas in the past, a 10 per cent decline in Brent crude could trigger double-digit naira depreciation, the current response has been far more muted.

Naira decoupling, however, does not mean insulation. The naira remains influenced by global investor sentiment, domestic inflation, and fiscal policy credibility. However, the reduced correlation with oil fluctuations suggests that Nigeria may be entering a new phase of exchange rate dynamics, one where macroeconomic policy and institutional reforms weigh more heavily than the unpredictable swings of the oil market. For investors, this implies a recalibration of risk models: oil price forecasts alone can no longer serve as a reliable predictor of naira stability due to the recent structural shifts.

THE NEW ANCHORS OF THE NAIRA

To properly situate this structural shift, let’s examine how certain economic variables that once moved in lockstep with oil are beginning to diverge. While oil prices and exchange rates, historically Nigeria’s most sensitive pairing, are now showing signs of detachment, other key macroeconomic forces have also begun to anchor the naira’s stability.

Inflation provides a revealing stress test. In early 2024, consumer prices surged by nearly 30 per cent. Historically, such a shock would have sent the naira into free-fall. Yet, the currency held its ground. This resilience shows that new anchors, such as a more flexible foreign exchange regime, rising non-oil inflows, improved fiscal discipline, and greater monetary credibility that boosted investor confidence, have begun to weigh more heavily on the naira’s stability.

Fiscal policy tells a similar story. The 2025 budget, premised on an exchange rate of ₦1,400 to the dollar and an oil benchmark of $75 per barrel, signalled that policymakers now plan around a more stable currency, even when oil prices move unpredictably. This marks a subtle but significant shift that the naira is no longer treated as a simple function of oil revenues. Equally important is the steady rise of non-oil exports and the credibility of a more transparent FX regime, both of which are beginning to underwrite the naira’s resilience.

Oil still matters, but it no longer holds the naira hostage. Instead, structural reforms and broader market forces are slowly re-anchoring the naira on firmer ground.

shop the republic

COMPARATIVE INSIGHTS FROM AFRICAN ECONOMIES

Nigeria’s experience with decoupling echoes a broader African dilemma. Angola, where oil still accounts for nearly 90 per cent of exports, remains heavily reliant on hydrocarbons, with high debt levels and fiscal risks persisting despite periodic revenue windfalls. Similarly, Equatorial Guinea and the Republic of Congo, both long-standing petrostates, have struggled to translate their vast hydrocarbon wealth into broad-based economic resilience.

By contrast, Ghana illustrates a more diversified, though fragile, pattern. While the cedi has remained volatile due to dependence on gold and cocoa exports, fiscal reforms have been aimed at stabilizing external balances. Botswana, on the other hand, demonstrates the benefits of prudent resource governance. Its long-standing management of diamond revenues through stabilization funds and investment in human capital has helped buffer the economy from commodity cycles, even if challenges remain in diversifying away from extractives.

These comparisons highlight that decoupling, or the failure thereof, is shaping the macroeconomic destiny of resource-rich African states. Nigeria’s emerging decoupling is therefore not unprecedented; it is anchored by FX liberalization, export growth and fiscal reforms, marking a distinct and potentially transformative trajectory.

IMPLICATIONS OF NAIRA DECOUPLING FOR NIGERIA’S ECONOMY

Naira decoupling from oil is a double-edged sword for Nigeria’s economy, combining opportunities for reform with significant short to medium-term risks. One of the most immediate benefits is the potential for greater exchange rate predictability. By weakening the rigid linkage between oil revenues and the naira, Nigeria reduces the extent to which fluctuations in global crude prices dictate macroeconomic stability. This is particularly important given the volatility of Brent and Bonny Light crude prices, which have experienced sharp swings in recent years. Furthermore, a stable naira fosters investor confidence, as foreign investors value transparent and market-reflective exchange rate regimes over artificially maintained pegs.

In the long run, decoupling also provides Nigeria with a platform to accelerate structural diversification. With oil contributing less than 10 per cent to GDP but over 91 per cent to export earnings, the shift could incentivize reforms that encourage investment in agriculture, manufacturing, ICT, and renewable energy sectors, broadening Nigeria’s productive base.

Nevertheless, the risks are equally pronounced. The most pressing concern is inflationary pressure. Since the June 2023 liberalization of the naira exchange rate, Nigeria has faced headline inflation surpassing 30 per cent, with food inflation hitting record highs. The depreciation of the naira against the dollar has directly translated into higher import costs, especially for fuel, machinery, and essential food items, as FX liquidity remains fragile and inconsistent.

Beyond macroeconomic stability, decoupling has distributional consequences. Exchange rates transmission disproportionately hurts low- and middle-income households, who spend a higher share of their income on imported goods. Unless accompanied by targeted social protection measures, reform fatigue and political backlash could stall the process. Thus, without a credible framework for fiscal discipline and revenue mobilization, the government risks falling back into oil-dependency cycles, where temporary fiscal windfalls from crude are mismanaged rather than invested in long-term capacity building.

OTHER DECOUPLINGS IN NIGERIA’S ECONOMY

While decoupling has been obvious in Nigeria’s evolving oil–naira relationship in a positive light, the notion of decoupling in economics is broader and manifests in multiple contexts with mixed implications (positive and negative) in the Nigerian economy.

Economic Growth vs. Employment

One of the most common forms of decoupling visible in the Nigerian economy is the disconnect between GDP growth and employment generation, often termed jobless growth. Jobless growth is an economic phenomenon where an economy experiences an increase in output (GDP growth) without a corresponding increase in employment. Economic theory suggests that an increase in economic output will drive job creation, making both variables correlated. However, decoupling occurs here when economic growth does not translate to job creation. We can describe this as negative decoupling, as is peculiar to Nigeria. Nigeria recorded an average GDP growth of approximately 1.76 per cent between 2017 and 2022. Yet, unemployment and underemployment rates remained persistently high, with a combined rate peaking at 56.1 per cent in Q4 2020

This trend of economic growth not alleviating labour market vulnerability is still evident today, even with a change in how the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) measures unemployment. For instance, while the official unemployment rate was reported as a much lower 5 per cent in Q3 2023 using the new methodology, other indicators from the same NBS survey paint a clearer picture: the informal employment rate remained extremely high at 92.3 per cent in Q3 2023. This represented a slight decrease from 92.7 per cent recorded in the previous quarter (Q2 2023). In addition, the time-related underemployment rate was 12.3 per cent in Q3 2023, a slight increase from 11.8 per cent recorded in Q2 2023. This shows that a large segment of the workforce remains in precarious, low-quality jobs, demonstrating the continuing disconnect between headline economic growth and meaningful employment generation in Nigeria.

Structural constraints, such as informality, technology, automation, skill mismatches, and the dominance of capital-intensive sectors like oil, mean growth fails to deliver inclusive labour market outcomes. This pattern is not unique to Nigeria. South Africa and Kenya also show rising productivity without commensurate employment gains, highlighting a continental trend of growth decoupled from welfare improvement.

Macroeconomic Stability vs. Living Standards

Decoupling also shows up in the real economy, where the economic growth numbers do not always match the realities on the ground. Nigeria’s recent reforms, for instance, have won international praise from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund for pursuing fiscal reforms, stabilizing inflation and exchange rates, projecting a picture of macroeconomic order. Yet, behind the statistics, these gains have not trickled down. A study by the World Food Programme revealed that in 2025, 33 million Nigerians will be at risk of food insecurity compared to 25 million in November 2024 amid surging costs caused by devaluation, inflation and subsidy removal. Today, the figure stands at 30.6 million people, which is a stark reminder that stability at the top does not automatically translate into welfare at the household level.

shop the republic

THE ROAD AHEAD

Decoupling is a multifaceted concept that cuts across different fields. It essentially explains a divergence between variables that normally move together (what economists call correlation). There have been several instances of decoupling in the Nigerian economy—from GDP-unemployment to macro stability-living standards, and finally, the oil-naira relationship.

Turning the spotlight on the latest movement between oil and the naira, the decoupling signals both a milestone and a warning for the future of Nigeria’s economy. It demonstrates Nigeria’s willingness to align its currency regime with economic fundamentals, a step necessary for long-term resilience. However, the sustainability of this transition depends on three fronts: sustaining credible monetary and fiscal policies, accelerating investments in infrastructure and local production, and building institutional trust to attract long-term capital.

If reforms are maintained, Nigeria could leverage the decoupling to build a more diversified and shock-resistant economy. Additionally, these measures could transform the naira decoupling into durable independence, freeing Nigeria from the resource curse by anchoring the naira on the strength of its people, policies, and productive economy rather than on oil wells. If neglected, divergence risks becoming a fleeting anomaly, a relapse into volatility, rising inequality, and persistent underdevelopment. Whatever path Nigeria chooses in the coming years will determine whether the naira’s break from oil becomes a turning point or a missed opportunity⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N3 An African Manual for Debugging Empire

₦40,000.00

US$49.99