In my family, the past had always been a sore subject. I hoped an ancestry test would change that.

The Black Atlantic is our newest column for nuanced, human stories about the Black experience around the world. Send your story.

Los Angeles, United States

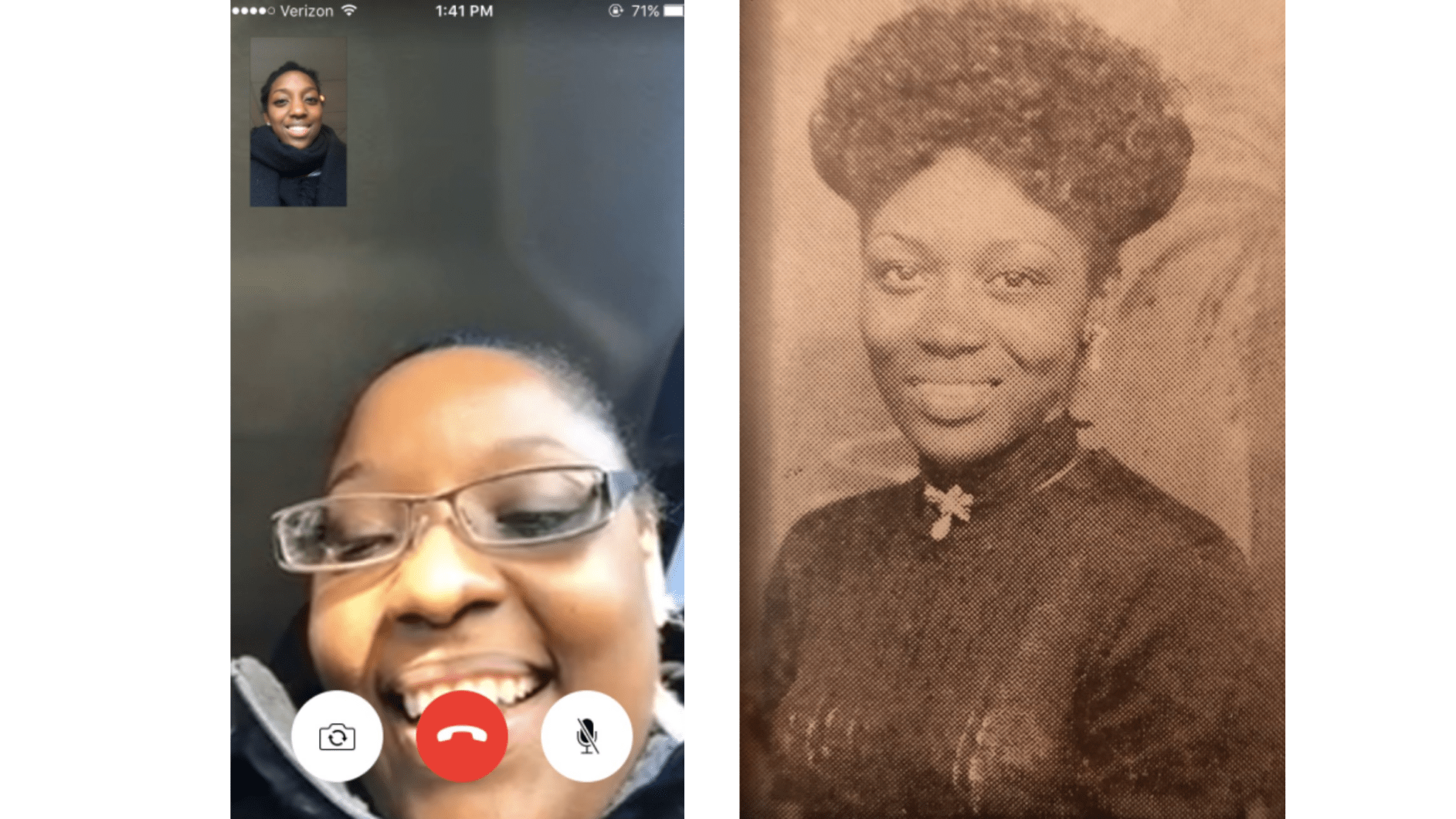

At the end of last year, I came across a sepia-stained picture on Twitter posted by writer, Genette Cordova, of her great-grandmother. Genette explained in the Tweet that she was killed by an ex-husband in the prime of her life. The story was made more haunting by the image Genette shared of her great-grandmother, who looked so much like me and my mother that I was inclined to reach out and send Genette a message. When I began drafting the message, I was unsure of what to ask. All my questions sounded archaic and overly sentimental:

‘Who are your people?

Where are you from?’

I found out she was from Texas by way of Oklahoma and that the father of the woman in the photo was a ‘full-blooded’ Choctaw man called Hosea Hill. In the US, this was and is a common mythology: Americans of all races who report their possession of some ‘Native blood’, usually attributed to a nondescript ancestor who was ‘part Cherokee’. Often, White settlers invented and perpetuated oral histories alleging Native ancestry to justify their claims to indigenous land, or, like me, to put distance between themselves and the more undesirable inheritances of a family lineage. For this reason, Native Americans based tribal enrolment on many factors—‘blood quantum’ or DNA and ancestry estimates, not being one of them. But for African Americans, such a lineage was not unusual. There was a storied history of relations between Native Americans and Black freedmen, specifically before Andrew Jackson’s Trail of Tears. Though I had no family in Texas or Oklahoma, three of four of my grandparents hailed from North Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, where much of the ‘Five Civilized Tribes’ lived before relocation, aligning mine and Genette’s histories. My curiosity piqued, after much indecision I decided to take a genetic ancestry test through the website, 23andMe. I collected a saliva sample and sent it away to their lab, which informed me that in 4-to-8 weeks I would receive the results.

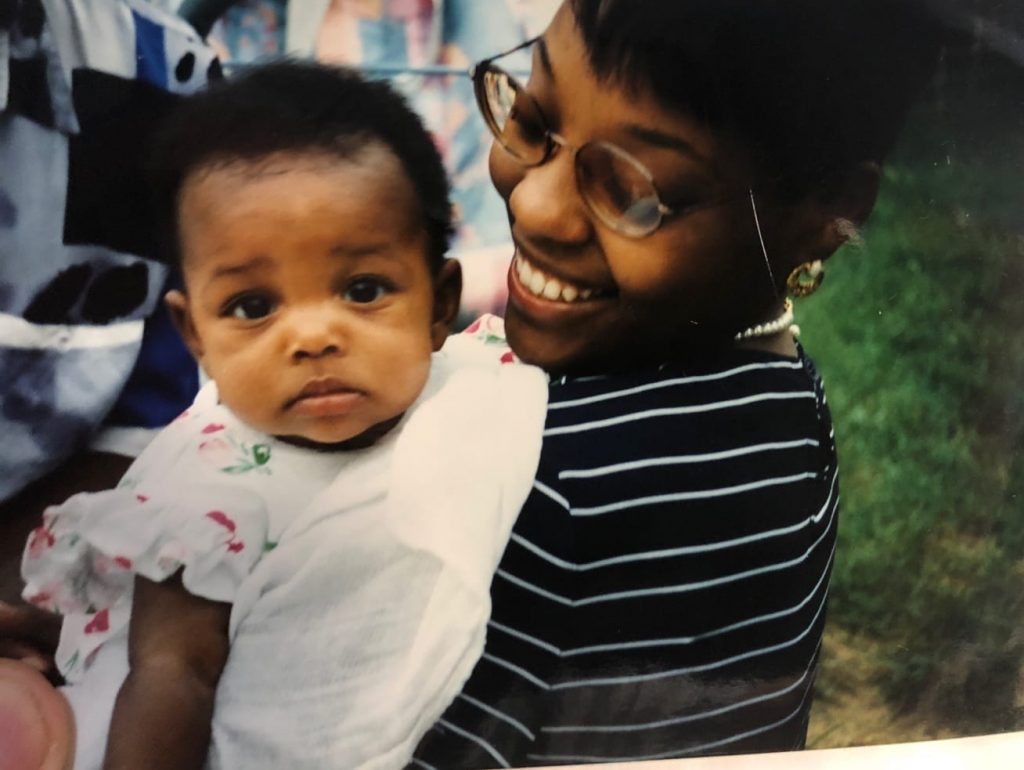

Perhaps it was no coincidence that, afraid my grandmother was dying, I sought out these results. Just the week or so before, my grandmother had been admitted to the hospital for shortness of breath. Faced with the imminence of her mortality, I grasped to the few memories I had of her now that her mind was years-withered by dementia. Months later, in her eulogy, I wrote that she was a fixture in my life such that sometimes, when I looked in the mirror or walked around my apartment barefoot, I still heard the tenor of her voice, especially in the summer, complimenting my freshly tanned skin.

As a child, I held great resentment for my skin. It was not so much the colour of the skin itself I resented but what, in America, the colour of my skin represented: a direct and unimpeachable line connecting my existence to the ignoble history of slavery. I felt this history most around the annual ‘waves of immigration’ lesson in grade school, where students would be forced to make a family tree. While my other classmates seemed to have no problem getting their parents to detail the colourful tales of their homelands, in my family, the past was a sore subject, best dealt with by moving on and leaving it where it lay. Annually this exercise would subvert this maxim: ‘Where are we from?’ I asked my parents repeatedly, I growing frustrated with their avoidance, them growing frustrated with my persistence. ‘We’re just Black, Jas.’ ‘Black what,’ I would say. ‘We have to come from somewhere.’

For a while, the one respite from this frustration was that of my great, great grandmother. I had never met her, never seen her, but had developed a sharp image of her in my mind because of the starry-eyed way my grandmother described her: ‘tall, beautiful, dark dark, skin, smooth as velvet, dark as midnight, hair down to here,’ and she would spin around and point a finger to her low-back. I grew up hearing that she, born in North Carolina, was either part or entirely ‘Indian’—that is, Native American, not of the Southeast Asian variety that I, confused and desperate to force distance between myself and slavery, erroneously reported to friends to much (merited) suspicion. My great-great grandmother was, at that time, the sole glimmer of light shone on the opacity of my origins. My knowledge of her made being Black something a bit more than what I understood as a long lineage of rootless pain and suffering. Instead, being Black was an inheritance of beauty, I could be proud was mine.

For four weeks I waited restlessly for the results, ravenous for any historical information that would substantiate my preferred outcomes. I am somewhat embarrassed to admit the thrill I felt imagining the delivery of scientific evidence that said I was more Native American than European. For a period, this thrill eclipsed my desire to answer my childhood question of where I was from. Briefly, I wondered if I should call up my second-grade teacher to let her know I was on the verge of some fascinating updates to that sorry family tree I submitted 20 years ago. Some concoction of both shame and pride had me putting so much stock in knowing about a history that might negate—or justify—my family’s experience beneath the long shadow of slavery and its effects. Proof that for some time, we triumphed over it with a more noble alliance, and this, rather than ignominy, was my true inheritance.

My frenzy was fuelled and informed by the work of the late historian, William Loren Katz, a friend of my aunt, the late Dr. Gloria I. Joseph, who introduced me to his work after I took a grand trip through the Western U.S., following my college graduation. His book, The Black West, details the contributions of Black and Native American people to the formation of the American West as we know it today. While writing, Katz came across so many accounts of the intimate political, social and interpersonal relationships between African Americans and Native Americans that he compiled the information in a follow-up work titled Black Indians. Through Katz’s Black Indians, I learned of elder African Americans who believed the opposite of me—that Native ancestry was much like that of their European ancestry: shameful and intrusive. Black awareness movements focused on African roots and over the mention of Indian, Native or any other ancestry less it be seen as ‘a denial of their African origins and the value of Blackness.’ A Black Seminole woman living in Texas, summarized this in 1943: ‘We’s culled people. I don’t say we don’t has no Injun blood, ‘cause we has. But we ain’t no Injuns. We’s culled people.’ Katz, however, argued that such beliefs hinder heritage worth further exploration, and perhaps most damagingly, ‘divide people today who could benefit from the unity forged by their ancestors.’

A month later, I received my results: I was of Sub-Saharan African (85 per cent), European (13 per cent), and Native American/East Asian (2 per cent) ancestry. At a speculative confidence interval, the Sub-Saharan African category was broken down into roughly two-thirds West African, the remainder Congolese and Angolan. My West African ancestry was comprised of Nigerian (35.9 per cent), Ghanaian, Liberian and Sierra Leonean (28.6 per cent), Senegambian and Guinean (1.5 per cent). The European consisted of British/Irish (10.4 per cent), Scandinavian (1.2 per cent) and Italian, Spanish, or Portuguese (0.9 per cent).

Epidemiologist Hans Rosling once said the world cannot be understood without numbers or with numbers alone. The only story confirmed by the numbers within my genetic results was the one I tacitly wanted to avoid all along: breadth of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the sexual violence which defined it. With no immediate White relatives to speak of, 99 per cent of my ‘relatives’ on the site had English or Irish ancestry. The African ancestry that made up the bulk of my genetic profile spanned the entire Western region from which indigenous Africans were taken during the Middle Passage—essentially just representing the union of the enslaved who were brought to the United States at different times, over time.

Nothing in the ancestry results could connect me to Genette’s great-grandmother beyond that she looked like my own mother and that our family histories were roughly similar. I decided then that, at their best, quantitative measures of ‘biology’ or ‘ancestry’ and ‘genealogy’ simply provide a skeletal framework, the bones of a history that can be substantiated only by the qualitative—storytelling, first-hand accounts, the oral histories—to give it blood and flesh; to transform numbers and data into art, culture, history. If Hosea Hill, a Choctaw man, was Genette’s second-great grandparent, the woman described by my grandmother would have been my second-great grandparent, making my third-great grandparent a Native man or woman. I knew my second-great grandfather was a mixed-race man of Dutch and African descent, who emigrated to the United States by way of the Caribbean island of St. Croix (at the time the Dutch West Indies before it became the USVI). This made my third-great grandfather, an entirely Dutch, or Scandinavian man. Scandinavian and Native American appeared in my results at roughly equal amounts. I considered it safe to surmise that Portuguese, Spanish, and Filipino results were likely related and combined, were, roughly equal to the occurrences of Scandinavian, Native American, so likely occurred around the same time period.

This was the one genuine surprise in my results, so I consulted the brief background 23andMe provided with the results. It said indigenous Filipinos descended from one of the earliest dispersals of humans out of Africa. However, the group began expanding into the Pacific, as far as Madagascar (in the West) and Hawaii (in the East), leading to the mixture of cultures that later emerged in the Pacific Islands as Polynesian and on the island of Madagascar as Malay. Ancestrally, for a person from the Philippines, New Zealand or Madagascar, this might more directly be the case, but in mine, it very may well be the result of some union following the little-known Philippine American War of 1899-1900, where Black soldiers, predominantly from the South, enlisted in hopes of gaining more freedom back home. However, when the soldiers realized they were fighting to deny Filipinos the autonomy they were fighting for at home in the US, some even deserted and joined the Filipino resistance to gain independence from Spain. On another hand, it could just as well be the remnant of the Spanish colonization of the major slave trading post of New Orleans. The diversity of ethnic and multicultural origins of Black people in America (and throughout the diaspora), beyond their long-ago connections to Africa, it seemed, were intentionally flattened in historical narratives in order to deny culpability in the opposing forces of violence and resistance that made us the people we are today.

Though extrapolation was an entertaining exercise, the information I was interested in—the bulk of who and where I am from—remained the more ambiguous. As a student abroad, working at the Hair and Skin Lab at the University of Cape Town, I had learned from my professor, Dr. Nonhlanhla Khumalo, about the complexity of African (and African descendent) genetics—but I did not connect how those limitations might affect my genetic results. First off, the 23andMe reference data set is a skewed sample—in classic case of survey bias, people who know they are of mixed ancestry are more likely to be curious about its specifics and people with more money are likely to be willing to make such a frivolous expenditure. In America, both those people are more likely to be White or close to it. As a result, roughly three times as many data sets were referenced to match my European ancestry, than my sub-Saharan African ancestry. In the most conservative reading of the data, over 80 per cent of my non-African genetic DNA was confirmed, compared to only slightly over a quarter (27 per cent) of my African ancestry, the rest unassigned to any specific region, nation or tribe.

Years after emancipation in America, the formerly enslaved would put ads in the paper looking for lost family members. Often, the ads were broad descriptions of people—generally including first names and rough estimates of who they belonged to and when. Today in America, finding our long-ago ancestors is nearly just as difficult. Writer and poet, Clint Smith, likened the process of recovering our lineage as African Americans to ‘chasing history through a cloud of smoke’—a cloud that initially only seemed to grow darker for me with my 23andMe results. Being ‘just Black’ was not opaque, I learned, but rather, made up of so much colour woven together that from afar it was hard to see through it.

I have considered giving up searching, giving up caring, resigning my history to the boundaries of America, but, while studying in South Africa a woman braiding my hair stopped and leaned over to ask if I was from Angola. Similarly, a colleague at Deutsche Bank in New York, once approached me after a meeting because she was certain I was Nigerian. Another colleague was certain that with my name and face I must hail from her island of Dominica. Haitians have approached me unprompted, saying they know another when they see one. When I worked in London, people said I must be Caribbean, in Colombia, Brazilian, in Brazil, Colombian. For a while I thought this made me rootless; I felt a sharp absence of connection to a singular homeland. But now, I consider that these individual encounters bring my ancestry more to life than anything genetic test results are able to tell me. Exploring one’s genealogy as a member of an indigenous population displaced by slavery can be a dispiriting and thankless endeavour, but what magic it is to be scrolling on Twitter, living halfway around the world, only for someone to see their face in mine⎈

The views, thoughts, and opinions published in The Republic belong solely to the author and are not necessarily the views of The Republic or its editors. We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editors by writing to editors@republic.com.ng.