Photography by Hadijjah Sebunya / THE REPUBLIC.

THE MINISTRY OF WORLD AFFAIRS

Kampala by Design

Photography by Hadijjah Sebunya / THE REPUBLIC.

THE MINISTRY OF WORLD AFFAIRS

Kampala by Design

When I was younger, I was told that this place was named after impalas. I imagined a stretch of wilderness decorated by gentle beasts and a white man in dark green safari attire baptizing the savannah woodlands, Kampala. It’s only after years of eavesdropping on Kalundi Serumaga that I learnt that before the imperialists/ explorers came, indigenous folk had their own vast and modern imagination for their stretch of wilderness. In hindsight, this should have been obvious.

I would like to highlight the modern because so often we imagine pre-colonial to be primitive or behind as an alternative to mainstream, current thought. Like architect and artist, Demas Nwoko, also argued, it is important that we see indigenous thought as modern, as forward-thinking such that we encourage its continuity and not stunt it as tradition. The draw to indigenous thought for me and many others I believe is not a superiority race, but a direction chosen out of the practical usefulness of indigenous thought to cater to the realities of colonized and oppressed peoples.

This feature essay is an exploration of three works, all within Kampala, Uganda that emulate the philosophy that unequivocally drove Nwoko. A desire to achieve natural synthesis in his projects. Utilizing organic materials from the lands where he was working. He picked up the generational call to decolonization and from the University of Ibadan attempted to release his and his peers’ minds from the chokehold that was neo-colonialism. While the Zaria art society as they came to be called, came as an obvious response to the lack of African teachers and thought in the curriculum, they were dubbed rebels by onlookers. The Zaria Rebels insisted on the continuation/ celebration of indigenous thought, and modernization. Nwoko’s work to date is interesting, bold, and creative. It does not suffer from the stuntedness of folks that pin Africa down to huts, granary and thatch. Within the authenticity, it is not just a return but a kind of leaping forward with great style and boundless imaginings. Lastly, Nwoko constantly argues that architecture cannot be separated from art. This is to say in not so many ways that buildings should be grand, should be cool, should make the occupant feel something. His notable works include the Dominican Mission Chapel, The Cultural Centre of Ibadan and the Benin Theatre.

I chose three buildings: the Kamwokya Community Centre, which is exceptional in its capacity to exist inconspicuously and still, yet remarkably for the marginalized community in Kampala’s ghettos. The Japanese Yamasen, which consulted with locals to build a modern environmentally friendly and sustainable solution in uptown Kampala and the pre-colonial United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) heritage site that preserved not just the tombs but the indigenous way of construction.

Often, Nwoko worked with raw materials and owing to his exceptional spatial understanding succeeded in achieving natural air circulation. For Uganda’s tropical climate, such spatial understanding is critical. Already achievable by the 19th century with the Kasubi tombs, this essay will also appreciate the mastery of convection currents evident at both Kasubi and Yamasen. The thatched roofing ensures that the structures are cool when it’s hot and warm when it’s cold. The community centre also achieves this with steel structures that allow for airflow. More impressively it conquers a flooding problem that is prevalent in the slum that it is located with butterfly roofing and a raised platform. The roofing system collects rainwater that can be utilized later. The raised platform complemented with an efficient drainage system protects the building from recurring floods. Given the climate crisis, I am most celebratory of the designs for their eco-friendliness.

Kampala is the capital city of Uganda, but also the royal capital of Buganda. The Baganda call it ‘kibuga’ which can be loosely translated to ‘city’. To understand the seismic conundrum that Kampala is in, the leading opposition figure, Robert Kyagulani Ssentamu, describes the city as no different from an apartheid territory. Some elite Baganda see the city as an occupied territory, given that their capital has been occupied by foreigners to their political marginalization and denigration; and others aspire for it to be a conglomeration of multi-cultural identities of cosmopolitan fashion. While there are many relevant ideological contests, the city is congested, has depleted sewage and drainage systems, bad roads, pollution and vast inequality, threatening the current semblance of harmony.

KASUBI TOMBS

The masterpiece is on a hillside occupying 30 hectares of Kampala district. The Kasubi tombs are honoured as a UNESCO World Heritage site in recognition of their cultural and spiritual significance to the Baganda people.

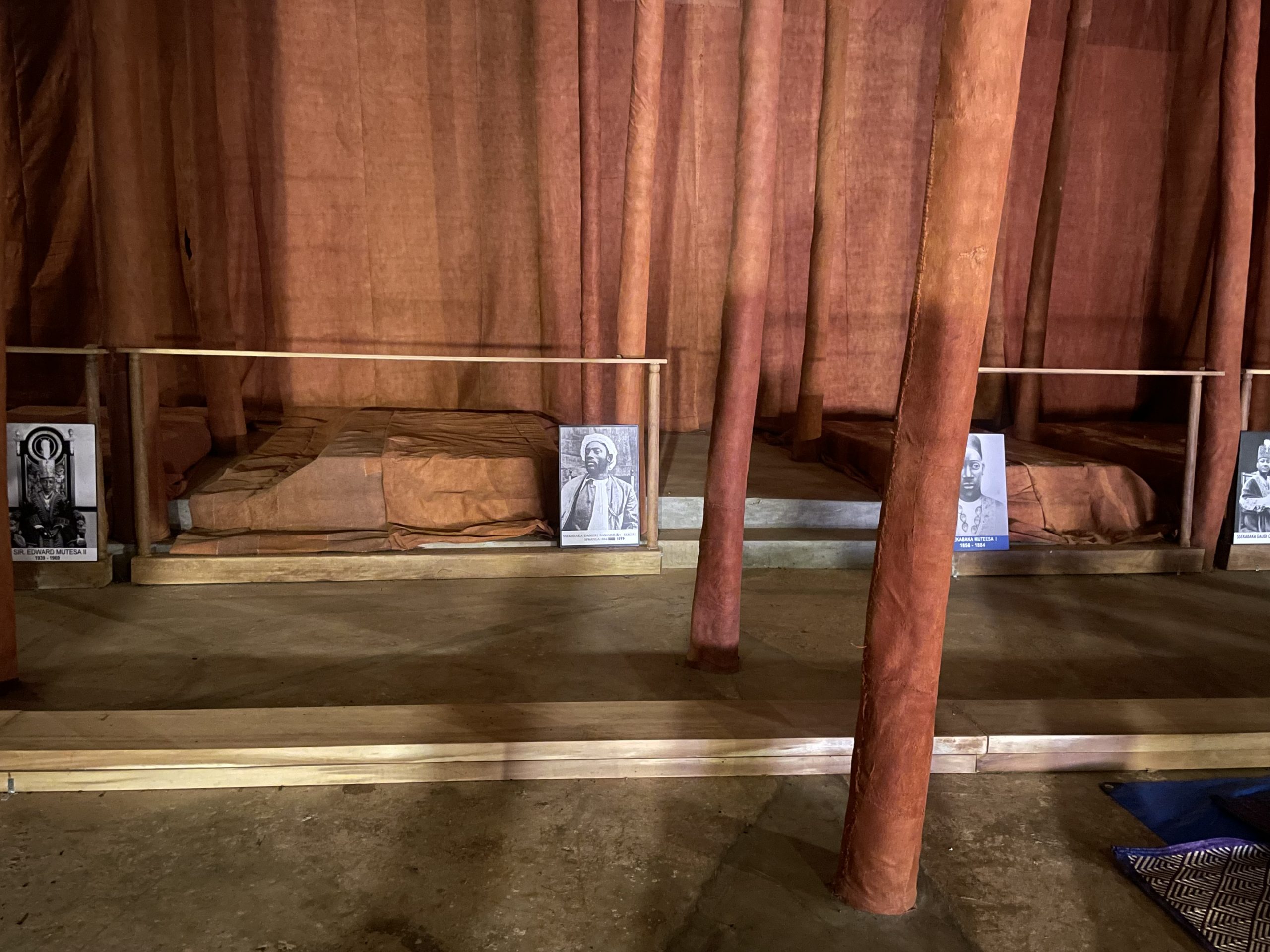

Muzibu Azaala Mpanga is the main structure of the burial and agricultural ground. The tomb is a spherical dome measuring 24.6 feet and 31 metres in diameter. The structures are composed of only organic botanical materials: wood, thatch, reed, wattle and daub. Kasubi tombs were first constructed by Kabaka Mutesa I, the 35th king of the Buganda kingdom owing to a change in burial culture introduced by the growing influence of Islam and Christianity at the time. In 2010, the structure caught on fire. Its reconstruction has been a commendable feat of 15 years and counting. In Buganda culture, kings are not believed to die, they are believed to go away into the forest behind Muzibu Azaala Mpanga. The tomb holds the metaphorical representation of their ‘caskets’ within the sacred forest the kings are believed to have transcended into. Kabaka Mutesa I, Kabaka Mwanga, Kabaka Daudi Chwa and Kabaka Mutesa II are separated by barkcloth and recognizable by a picture in front of the casket.

The ‘interior design of the tomb’ was carried out by the designated Ngo (Leopard) clan with the assistance of the Ngeye clan. The thatching of the tomb was designated to the Ngeye (Colobus Monkey) clan. All the artisans deployed to work on this building were selected strictly from these clans. Without historical context, some of these decolonial feats are easy to gloss over. While the re-construction can be observed as a decolonial practice, some scholars such as Kigongo and Reid argue that the management and custodianship of the tombs does not satisfy a full decolonization but rather a post-colonial accommodation and negotiation with the Ugandan state. In order to determine who had authority over consultation, for example, different mediums claimed connection to different kabaka. Eventually, the medium that claimed to be speaking with Kintu, who is believed to be the beginning of Buganda outbid everyone else. The reconstruction was not a perfect science given the deliberate imperialist erasure therefore, rebuilding relies on memory, mediums, and potentially inaccurate post-colonial descriptions of the site. Furthermore, the kingdom’s restoration remains a political threat to the state as well as to Christianity which holds a strong place in Uganda. For example, one of the kings, Mwanga and his infamous attack on early converts as the Christian story is told as well as shrine worshipping competing with the idea of idolatry that is demonized in the Christian faith. Baganda, despite its strong Christian and Muslim influence, also believes in mediums. In fact, a medium was consulted for instruction on the reconstruction of the tomb. There are also numerous rituals that need to be done along with the reconstruction. Surrounding the masiro as they are described in Luganda, are other shrines/tombs taken care of by the descendants’ wives and sisters.

The reception of the monument seems to be more with the elite Baganda and elite tourists than with the average Ugandan. While it is true that many still make use of the monument to pray and indeed the place is always open for that, the commercialization of the site is evident. When I went there, the guide tried to extort me thinking I was a foreigner. Harding also writes about how fake ritualists at the site need to be stopped. Still, this is not entirely detrimental to the higher purpose and the long run of reconstructing a site as significant as the Kasubi tombs.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00

TREASURE LIFE YOUTH CENTRE (KAMWOKYA COMMUNITY CENTRE)

The Kamwokya Christian Caring Centre in partnership with the Switzerland-based Foundation Ameropa constructed an indoor stadium in the heart of Kampala’s poorest areas. From the construction, where members of the community were employed to be labourers to the utilization of the facility, the project has directly benefited its most immediate counterparts.

A testament to this was my inability to find the location without directions. Neither the boda guy (motorcycle driver) nor I could locate the place with GPS and without the assistance of the locals, not from a poor sense of direction but because of how inconspicuous the stadium is. It is almost impossible for a car to find its way to the stadium making it more accessible for its intended users that would either be walking or on a boda-boda.

Kamwokya is a slum. An informal settlement located approximately four kilometres northeast of Kampala’s city centre. In Kamwokya many live with the indignity of no sewage systems. I will spare you the poverty porn, but I must emphasize the inhumanity of the conditions that the people are forced to live in. While there is indeed a great show of the human spirit, with plenty of shops, and small businesses, the residents do not have the dignity of privacy and distinguishment; I pass the same small naked boy open the door to pee shamelessly into the road outside his house that is gated from the outside only by a beautiful lesu (sarong) quite often. I visited when the sun was bright and shining but I can imagine that with the rains comes flooding that is more than likely to encroach into people’s homes, carrying sewage. Unprompted, my boda-guy informs me that he could not be paid to live here.

shop the republic

Outside the gate is a corner store. The shopkeeper let me know that that day, I would need permission to enter the stadium. It’s 11 a.m., and the centre is closed. I try to charm the gateman who insists that the only person he can take orders from is the woman who sits in the office. I walk over to find her in a meeting. She is generous with her time and allows me to take a tour and all the pictures. The building is exactly as I have seen it digitally; extremely well taken care of. At the back, I am impressed with the child safety guidelines. There are children playing inside, they appear to be training for a serious competition.

The multi-purpose stadium is so specific to the community that there is an overnight parking for boda-bodas. The immediate hurdle for the community is flooding and this has been addressed with drainage and a raised platform. Natural air circulation has been achieved with the butterfly roofs as well as the numerous vents seen across the building.

Kampala by design does not have this many people within it. It was designated for a few imperialists who did not in fact wish to settle in the Ugandan territory. After independence, given its status as a capital city, the city continued to attract people from all over the nation. Many live in slums, with more slums coming up in the city to cope with the depleting socio-economic status of the country under a brutal military dictatorship. Solutions like the Kamwokya Christian Community Centre are very impressive, and while they do not address the existential questions of national identity, they address very pressing issues.

shop the republic

YAMASEN

Yamasen is a fairly new work on Kampala’s terrain. Set up in 2018 by lead architects Ikko Kobayashi, Fumi Kashimura, Shinnosuke Yamashita and Albert Wasswa, the architecture can be safely categorized as contemporary. The building got enough buzz from the locals but has also been internationally celebrated with the Good Design Award.

Yamasen is a Japanese ‘farm-to-table’ restaurant. The menu reflects the organic use of materials and is an outstanding display of sustainability and eco-friendliness before and after construction. Yamasen is also one of the only places in Kampala where one gets seafood that won’t make you sick. A nod to its trade with Tanzania. On an existential level, Yamasen is a testament to how fast the world is becoming globalized, further challenging the ethno-nationalistic/ decolonial return/ liberation of Kampala to the capital of Buganda. New additions to the building are two clearly Japanese paintings hanging from the ceiling. A conversation with one of the workers taught me that it costs someone from Japan about $2,500 to gain a permit visa. Despite home appearing better by the usual metrics that measure the standard of living, the worker is happy to be in Uganda and has even adopted a Ugandan name. ‘Japan is unbearable to live in, I feel free here despite the political problems, I would rather live here.’ Her journey in the country has not been easier because she is foreign and one can even say that she has faced significantly more exploitation because of it. Comparatively, however, she feels that it’s better to be a pioneer in Uganda than another cog in a machine back home. The world is changing. There seems to be an equal number of Japanese and Ugandan workers.

The roof structures are made of local eucalyptus. I learnt from this project that usually eucalyptus is reserved for roof trusses but the architects innovatively with drying and lumbering tackled the challenge posed by the fragility of the material that was prone to breaking, bending etc.

It is also worth noting that the eucalyptus was sourced from within the local community, providing income but also future incentives for emulation and market for growers. Yamasen is a two-storey multi-purpose building that attracts a multicultural and affluent class in society. It is bound to influence the imagination of society and challenge the notion that good buildings are air-conditioned skyscrapers. Sharing the building with the restaurant is a cafe house that attracts internet surfers, entrepreneurs and freelancers. For many, this is also a networking opportunity, a chance to gain proximity to potential investors, partners or markets for their start-ups and employers for menial jobs with better pay. In the bathroom is a notice about a free jazz concert to be put on later.

The restaurant is surrounded by five pre-existing trees that the architects chose to build around. This incorporation of nature within the architecture can also be seen in other neighbourhoods around Kampala: most recently the similarly affluent Endiro Nakasero that actually has a tree growing through its centre and further out through the roof.

The three buildings have each addressed the challenges of Kampala differently. Yamasen showed how Kampala can develop in a cosmopolitan fashion, self-correcting for capitalism errors as the world becomes more conscious of itself. Kasubi tombs show how we can return and enrich our imaginations to answer the existential questions that perhaps trap our imagination and prohibit authentic self-determination. The Christian Community Centre is fixated on immediate reality and addresses the very real problems humiliating everyday people in the here and now. All of these buildings would be embraced by the Zaria rebel society and in their own way meet the philosophy of Nwoko⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page