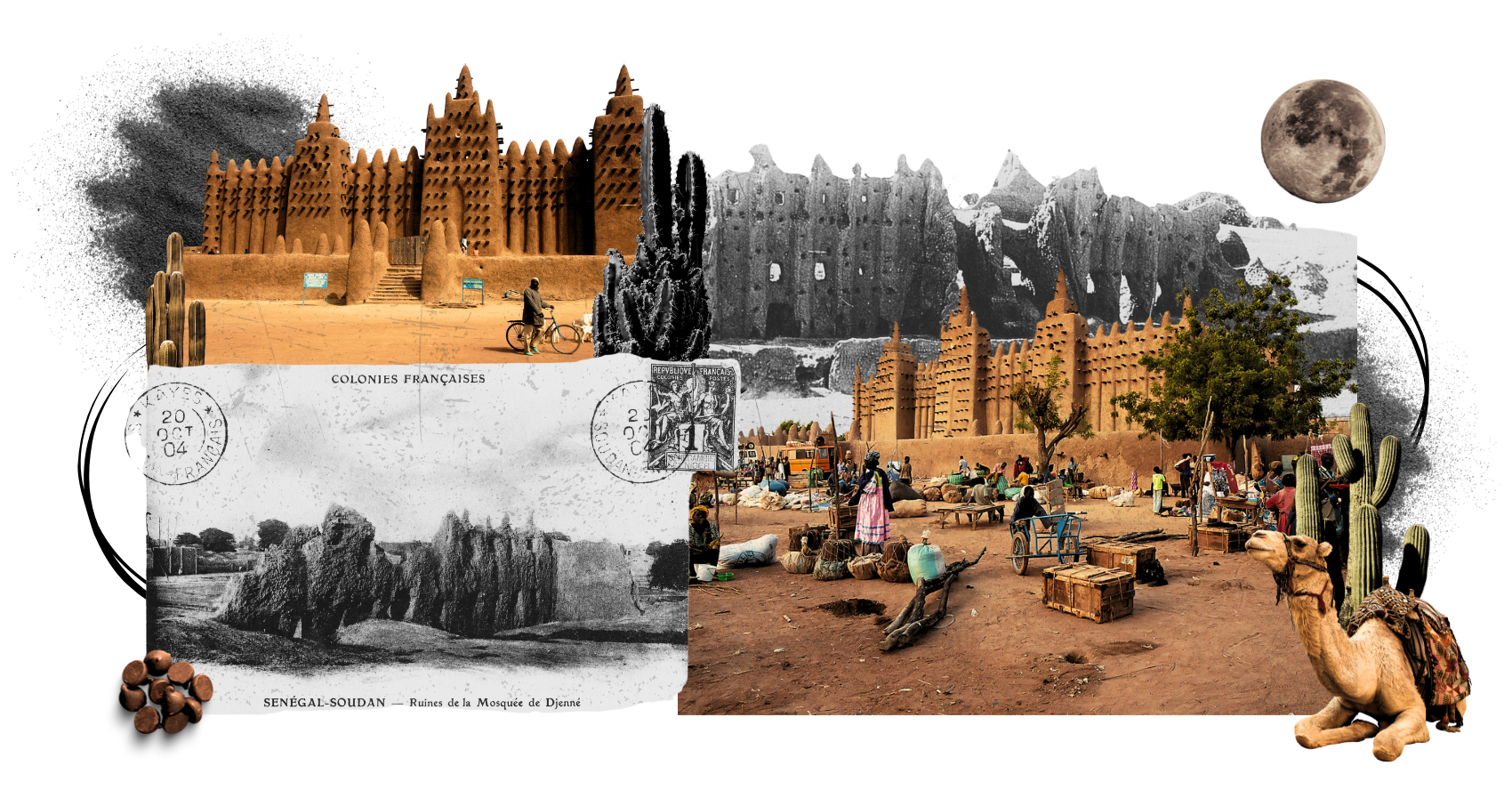

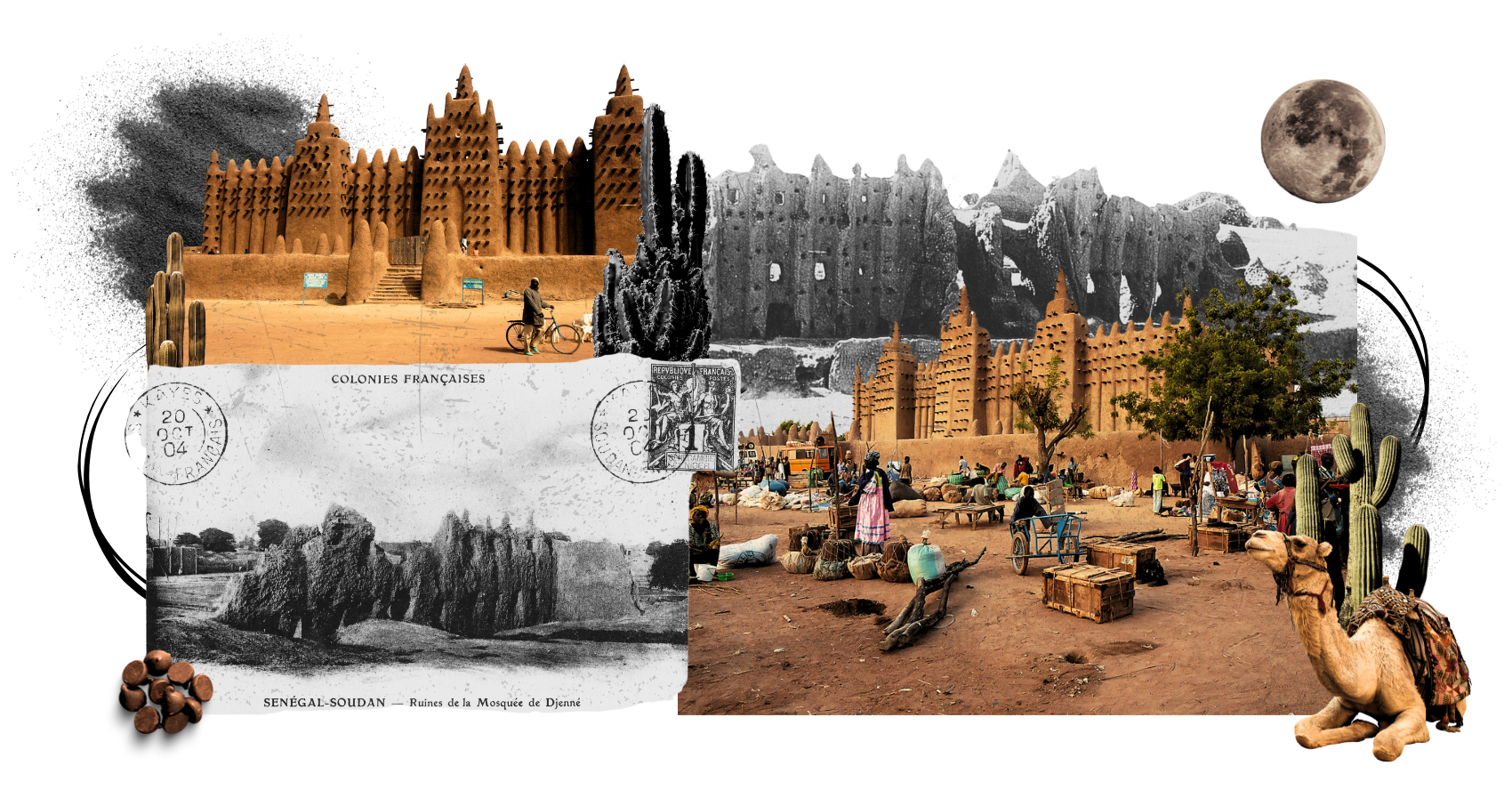

Photo illustration by Dami Mojid / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref: WIKIMEDIA.

THE MINISTRY OF MEMORIES

The Great Mosque of Djenné And the Social Utility of History

Photo illustration by Dami Mojid / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref: WIKIMEDIA.

THE MINISTRY OF MEMORIES

The Great Mosque of Djenné And the Social Utility of History

The Great Mosque of Djenné, located in the Mopti district in central Mali, was built in the 13th century, making it one of the oldest structures on the African continent, let alone the world. Indeed, the town of Djenné is also one of the oldest urban settlements in Africa, with roots back to at least 250 BCE—on par with cities such as Alexandria, Egypt (c. 300s BCE), Benghazi, Libya (c. 500s BCE), and Aksum, Ethiopia (c. 400s BCE).

However, its complex history of being destroyed and then rebuilt during the colonial era poses a challenge to the concept of preservation and history. The scaffolding of the Western epistemological approach to preservation and history is constructed by the ability to describe longevity in a linear, unbroken sequence. By these standards, the genuineness of the mosque’s physical structure is called into question. However, the annual festival of restoring the mud-brick walls, called fête de la crepissage, an ancient, enduring practice, offers a rebuttal. Firstly, the fête de la crepissage directly reflects the long-standing social utility of the mosque and thus rejects its mummification and relegation as an inanimate, inoperative object, much like many of the ritually charged African ‘artefacts’ stored in museums across the world. Secondly, the fête de la crepissage also implies the social utility of history.

In 2000, historian, Adiele Afigbo, delivered a lecture at the Centre for Black and African Arts Civilization in Lagos, entitled ‘The Black Man, History, and Responsibility’. He remarked that ‘by its nature and the way it is practised, history is both science and ideology.’ However, in ‘the final construct,’ history is ‘more often ideology than science especially as it cannot be tested for being true or for the ability to produce any particular effect.’ Nevertheless, he asserts, it is a very important pursuit for it helps to create the environment of empowerment without which nothing can be achieved in the realm of social action.’ Similarly, almost 25 years earlier, historians, J. F. Ade. Ajayi and E. J. Alagoa, tell us in their 1974 article ‘Black Africa: The Historians’ Perspective’, that the purpose of history in pre-colonial African societies, was to ‘provide a sense of continuity,’ for the purposes of explaining to, ‘each person and to each people where they fit into the scheme of things.’ This is important because a person’s ‘self-perception is vital to what [they] do,’ and their self-perception is still ‘largely the result’ of their ‘view of history.’ Note, they assert that the view of history, not simply the recounting of history, is directly related to self-perception and subsequently one’s actions. Such a qualifier is necessary because one, it reveals the human agency required in the processing of history. Two, it also challenges the Western approach to history which displays history as an objective, linear, sequenced recounting of ‘facts’, as its end, rather than understanding history as a social utility, or a means toward self and communal health. If one were to take the former approach, the genuineness of the modern-day Djenné Mosque can never realize its full glory of being one of the oldest world heritage sites. If one takes the latter approach, we find that the continuity which is sought in the name of ‘preservation’ exists among the Malians who actively engage as part of their daily lives, and certainly in the fête de la crepissage.

ORIGINS AND ITERATIONS

In his 1987 article, ‘The History of the Great Mosques of Djenné’, architectural historian, Jean-Louis Bourgeois, tells us that evidence pertaining to the original Mosque thought to be built in the 13th century is murky at best. Bourgeois points us to an oral tradition in which one Koi Konboro, the ruler of Djenné, converted to Islam and built the mosque only after attempting to exile or kill a Muslim cleric named Ismaila of whom he grew suspicious. After Konboro’s efforts were thwarted seemingly by divine intervention, Konboro converted to Islam and had the mosque built. The Mosque, ‘the pride of Djenne’, was from then on replastered every year until the 19th century, ‘when it met a formidable adversary in Sekou Amadou,’ founder of the Fulbe Empire at Masina, less than 500 kilometres from Djenné. Malian historian, Amadou Hampâté Bâ, writes in his 2021 book, Amkoullel, the Fula Boy, that Sekou Amadou was the ‘elder son’ of El Hadj Omar, also known as ‘Umar Tal. ‘Umar Tal established the Tukulor empire in the 1850s spanning from the inland upper Senegal River to the Niger River bend. Though it would be ‘Umar Tal’s nephew, Tidjani Tall, who would succeed the king and establish his base at Massina 400 kilometres west of Djenné, Amadou would gain control of Bandigara, less than 200 kilometres to Djenné’s east. Launching a Fulbe-led Islamic reformist movement, he erected his own mosque at his capital of Hamdallahi, requiring that all citizens attend this mosque, at the expense of the others. Bourgeois writes that, ‘before Amadou built his own mosque in Djenné, it is likely that he refused to allow proper maintenance of the old one.’ Moreover, though appeals on the preservation of the mosque flooded his court, Amadou and his council, ‘decided that the mosque should be abandoned entirely, claiming the Moroccans who conquered Djenné in 1591 had corrupted the monument.’ In the final hour, ‘subterfuge’ prevailed when Amadou, ‘plugged the Great Mosque’s gutters,’ and ‘rain collected in a pool on the roof, which collapsed, exposing the mosque’s massive earthen pillars,’—the importance of the annual restoration as both an architectural and social process revealed.

But it is not just that Amadou destroyed the mosque, leaving its ruins, and rebuilt another a few kilometres east. He also spun intricate webs of historical fabrication, which suggests the mosque was rebuilt a number of times, including once by the notable Askia Muhammad of the Songhay empire before its collapse due to Moroccan invasion. Ultimately, Amadou saw the mosque and the history of the mosque as a tool to justify his rule and his actions—for a Muslim to destroy a mosque is perhaps one of the highest transgressions. Nevertheless, each fabrication, regardless of their status of untruth, is part of the collective tapestry that makes up the history of Djenné. Amadou illustrates how one applies history as a tool, rather than an end to itself.

Social anthropologist, Trevor H.J. Marchand, writes in his 2015 essay, ‘The Djenné Mosque: World Heritage and Social Renewal in a West African Town’, that Djenné would fully fall into the hands of French colonialism in 1893. Amadou’s reign, Hampâté Bâ tells us, would come to an end at the hands of the French, who by 1897 drove him out towards the Sokoto Caliphate region closer to modern-day Burkina Faso. In 1906, the French ‘razed’ Amadou’s ‘ascetic mosque that same year, and in its place, they erected a [madrasa] to school their new colonial subjects in both French and Arabic language.’ That same year, they also initiated the reconstruction of the ‘weatherworn ruins of Koi Konboro’s original structure.’ However, as both Marchand and Bourgeois argue, while the French had the so-called right of rule, it was Africans who dealt with the logistics of the reconstruction.

Bourgeois writes that the people of Djenné were at a ‘crossroads’ because ‘the issue, crucial to the city’s identity, was to choose between versions of it’s past.’ The crossroads was a trivariate: One, to build on the site of the ruined mosque completing, ‘the process of demolition that Sekou Amadou himself had dared only to initiate.’ Two, building on open land, and three, building on the site of Amadou’s Mosque, the option which prevailed to the dismay of the Fulbe. Yet, the utility of history emerges again. Oumar Sanfo, a notable 19th century Muslim ‘savant’ critical to the resistance against Amadou, ‘quietly invited the French to raze Amadou’s Mosque,’ so that the ‘sin of obliterating the mosque was transferred to them.’ The most contemporary iteration of the Great Mosque of Djenné, seemingly erected by French colonialism, is actually part of the intricate narrative of Malian intrigue, beginning with Koi Konboro.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00

THE SOCIAL UTILITY OF THE STRUCTURE

Only six years later, Hampâté Bâ would see the Great Mosque for the first time as a young boy travelling for ‘The White Man’s School.’ He describes the ‘reputed beauty’ of the Mosque as ‘confimed in the spires of the three pyramid-shaped turrets as they rose above a mass of greenery,’ while the

ends of palm tree trunks embedded in the structure to ensure the stability of the building bristled artfully from the facade, and its delicate ochre spires stood out against a clear sky that seemed to have been washed and dyed blue by the very hand of God.

Finally, he remarks that ‘In those days, it was the most beautiful mosque in all sub-Saharan Africa.’ However, complexities around the historical genuineness of its construction come into question in the context of French colonialism. Nevertheless, directly referring to Bourgeois, Marchand argues that ‘the present structure was designed, engineered, and built not by the French, but by local masons, with logistical and economic support from a resident population that was energized by a jubilant spirit of independence from their former [Fulbe] oppressors.’ It seemed fated, as history often does, that the 1907 construction through conscripted or forced African labour would be led by one Ismaila Traoré–the same name associated with the first mosque built by Konboro.

With all the strands of history that have passed through Djenné and specifically the Great Mosque, the structure itself is a vessel of social cohesion. In his 1987 book, Precolonial Black Africa: A Comparative Study of The Political And Social Systems of Europe And Black Africa, from Antiquity to the Formation of Modern States, Cheikh Anta Diop points us to the thirteenth-century prayer of Koi Konboro, in which he supplicated, ‘that the city be peopled by a number of foreigners greater than that of its citizens.’ Over the centuries Djenné has seen the fulfilment of this prayer, in part negotiated by the perpetual presence of the Great Mosque. Indeed, Hampâté Bâ reminisces on his youth travelling to Djenné for school and witnessing the Mosque: ‘Was it not said that this city, the most beautiful of the entire Niger Bend, was located just above Al-Djennat, the garden of Allah (paradise), for which it was named?’ Marchand writes that, ‘The weekly procession of men to and from the mosque is an essential ingredient in Djenné’s social glue.’ In coming together for the Salat al-jum’a (Friday prayer) is a reminder that Djenné is a place, ‘populated by myriad ethnic and language groups and steeped in a long history of multiculturalism.’ He continues:

Sharing the mosque on a regular basis helps to bridge the steep socioeconomic divides and cultural differences that strain daily cohabitation, and it lubricates negotiations of shared civic identity. Equally, the mosque can become a stage for civic competition and even the violent contestation over the control and ownership of Djenne’s cultural heritage and, in effect, Djennenké identity.

Pointing back to Ajayi and Alagoa, we see that the preservation of history and/or the mosque is not an end in itself, but it has for centuries been a means for people of all social classes to negotiate self and communal perception. This negotiation is not exercised simply through the existence of the structure but of people’s very engagement with that structure. It is through this human engagement and agency that preservation even occurs, rather than the preservation catalyzing human engagement and agency.

The human agency and social utility of the mosque cuts through the fact that the current iteration of the Great Mosque was built under the supervision of French colonialism, or that previous iterations may have been destroyed and rebuilt. That the structures themselves do not necessarily bear the hallmark of genuineness is refuted by the very fact that it is constantly restored through the same social process which initially brought it into and sustains its existence. Moreover, the obsession with things ‘ancient’, obscures the fact that these feats from the Djenne Mosque to the Asantehene golden stool, the Sika ‘dwa, were just as much intended to establish claims to antiquity as they were created with the goal of propelling the community into a new era. From ancestral supplication of Ifá to Mande oral traditions, which collapse and weave intricate timeline patterns, the past is very much a part of the present. In this way, the past is not distinguished by its distance away from the present, but its closeness manifests in the everyday lives and practices of the people.

shop the republic

THE BAREY TON AND DJENNENKÉ SOCIETY

Often times, the fête de la crepissage is portrayed as a frenzied free-for-all by the masses, especially those looking to accumulate good deeds in the eyes of Allah. However, Djenné has a critical history of skilled masonry–indeed, as Marchand remarks, the 1907 construction was largely organized by the efforts of the indigenous masons’ professional association, the barey ton. The construction, reconstruction and continual restoration of the mosque was and still is, in part, and built on skilled labour, passed down through generational apprenticeship through this association. In another essay entitled, ‘Muscles, Morals and Mind: Craft Apprenticeship and the Formation of Person’, Marchand discusses how the barey ton is male-centred, centuries-old, and ‘most are initiated in the work as children,’ as young as six or seven, ‘who follow fathers, uncles and older siblings to construction sites.’ He continues:

Through listening to negotiations and disputes with clients, suppliers, team members and other masons, he becomes further immersed in the concerns, worldview and social behaviour of his mentor. In combination with the secrets he gleans, these factors forge the builder’s identity as a recognized member of the masons’ trade association.

It is through the child’s active participation in the simultaneous making and preservation of Djennénke history that this child grows into not only their self-perception but also their perception of their community. The mundanity which the apprentice must learn to master and then surpass also ‘expands his understanding of the division of labour on a construction site and coerces him to think and act as a team member.’ It is under these circumstances that he learns to ‘issue and receive directives, to temper his emotional displays of anger and frustration, and to earn the respect of all levels in the hierarchy.’ In other words, to borrow from Ajayi and Alagoa, through the process of literally making and preserving history, the mason apprentice gathers, ‘a sense of continuity,’ and an understanding of, ‘where they fit into the scheme of things.’

As the mason is to the Barey ton, so is the Barey ton to the Djennenké. Through their instrumental role in organizing the fête de la crepissage, their place in Djennenké society and history is understood. Marchand writes that for the fête de la crepissage, ‘an auspicious day was negotiated between town elders and the Barey ton chief, and was publicly declared with little forewarning,’ upon whence, ‘preparations had to begin immediately—and energetically.’ Men and women were and are tasked with the logistical organization of the festival. However, class tensions no doubt present before European arrival, but no less doubt exacerbated by European presence, have emerged to examine the role and contemporary utility of a mason’s guild with skilled knowledge purposely withheld from the common people who are involved in the festival. Indeed, as we will recall, the 1907 construction and perhaps previous constructions were built with forced labour–not uncommon for most of the world’s greatest monuments.

shop the republic

PRESERVATION IS A PUBLIC AFFAIR

While the Barey ton and Malian government officials control the organization of the fête de la crepissage, a battle seemingly between architectural integrity and social utility has come to a head in recent decades. In 2006, discusses Marchand, a team of ‘technical experts’ from the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) arrived in Djenné, with a ‘signed agreement of cooperation,’ with former President Amadou Toumani Touré for the restoration of the mosques in Mopti, Timbuktu and Djenné. After barely a week of survey work, Marchand relays, ‘rumours about illicit foreigners spoiling the mosque, digging for sacred treasures, or secretly planting a computer device in the building spread through Djenné like a brush fire.’ A riot subsequently broke out, largely composed of youths, leading to at least one death and damage to ‘displays of archaeological objects,’ in the courtyard of the Cultural Mission, and (of course) to the Mosque’s Imam’s three cars.

On the former, if this was simply about the preservation of history, why destroy other ‘archaeological’ objects? Marchand argues that most of the young people implicated in the riots come from communities that reap, ‘little or no economic benefit from tourism, development or the few employment opportunities that the politics of cultural heritage bring to the town.’ Rather, ‘the heritage projects are popularly perceived as “cash cows”, exclusively benefiting a select, privileged and “corrupt” circle of civil and religious office holders.’

The division caused by centralized administration, guarded associations like the Barey ton, exacerbated by the critical underdevelopment created by centuries of European imposition, catalyzed, ‘a widespread sense of impotence and exclusion from the centres of power and decision-making that directly affects the homes people live in and the buildings where they pray and socialise and which they maintain as a community.’

Nevertheless, in January 2009, the AKTC returned and successfully collaborated with the ‘various parties involved’ to begin the restoration of the Great Mosque. Perhaps learning their lesson from 2006, ‘under the stewardship of an international team of architects and in close collaboration with the town’s Barey ton masons and local labourers,’ the work site was ‘positively promoted as a forum for “fruitful exchange” between the foreign experts and the masons.’ Specifically, it was promoted as ‘a place for training and for improving earthen technologies that would be transferrable to other historic buildings.’ The implication here is that Djennenké masons and labourers—Djennenké people—would stay in control of such projects by learning new processes for longevity, rather than having to continually rely on foreign expertise in the future.

However, despite renovations, in November 2009, due to heavy rainfall, the sections of the Mosque collapsed, leading to deeper examination that revealed the precarity of the structure. In a report published by the AKTC in late January 2010, notes Marchand, it was noted that the annual re-claying ceremony was failing to supply the technical maintenance necessary for the building’s long-term preservation.’ The AKTC recommended that for future practice, ‘the masons should play a central role in preparing the materials and overseeing the annual re-claying; and, on the days following the festivity, the masons should conduct technical surveys and carry out the more delicate repairs and maintenance.’ Finally, it was agreed, ‘that a century’s worth of accumulated plaster be removed from the building envelope in order to execute the necessary structural repairs,’ the result is that, ‘this exercise would also restore the mosque to its “original” 1907 form.’

Yet, this restoration to the ‘original’, as structurally necessary as it might be, must come into consideration with its social utility, which has by far surpassed the structure itself. Sure, the Mosque may have collapsed. But as we have seen, the Mosque has already been destroyed once, and it was the labour of African craftspeople who erected it once again, demonstrating its roots in social utility. Certainly, Africans—or anyone for that matter—should not be opposed to calling on ‘foreign’ expertise if needed; at the same time, those experts called upon should fully cooperate within the parameters prescribed by the people, rather than approaching with their intention of preservation.

HISTORY IS A MEANS

It is not the structure by itself which is imbued with meaning; the very fact that it is made by indigenous materials that it is under constant threat of being washed away if not for the fête de la crepissage. That is, it is the human agency employed in the festival which gives the structure meaning, it is not the structure which gives the Djennénken meaning. Similarly, Frantz Fanon remarks in his 1952 seminal text, Black Skin, White Masks, that, ‘the future should be an edifice supported by living men.’ Indeed, Afigbo discusses the importance of causation in the practice of history. He writes, ‘to become fully human, to make himself, the Blackman does not only need to know that he has the capacity to be the cause, but that indeed he has to be so in theory and in practice.’ One does not just shape the future but equally shapes the past through their actions in the present moment. Fanon had a similar outlook. He remarks that the future, ‘is not the future of the cosmos, but rather the future of my century, my country, my existence.’ At the same time, he argues that ‘in no fashion should [one] undertake to prepare the world that will come later. I belong irreducibly to my time.’ However, this is not to suggest that one has no responsibility to the future, but that they must demonstrate responsibility to the future by employing agency in the present moment. As the Great Mosque of Djenné demonstrates, it is this human impetus that weaves together the strands of the past, present and future in an infinite continuum, which branches off in tributaries and bifurcations⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page