The Great Mosque of Djenné and the Social Utility of History

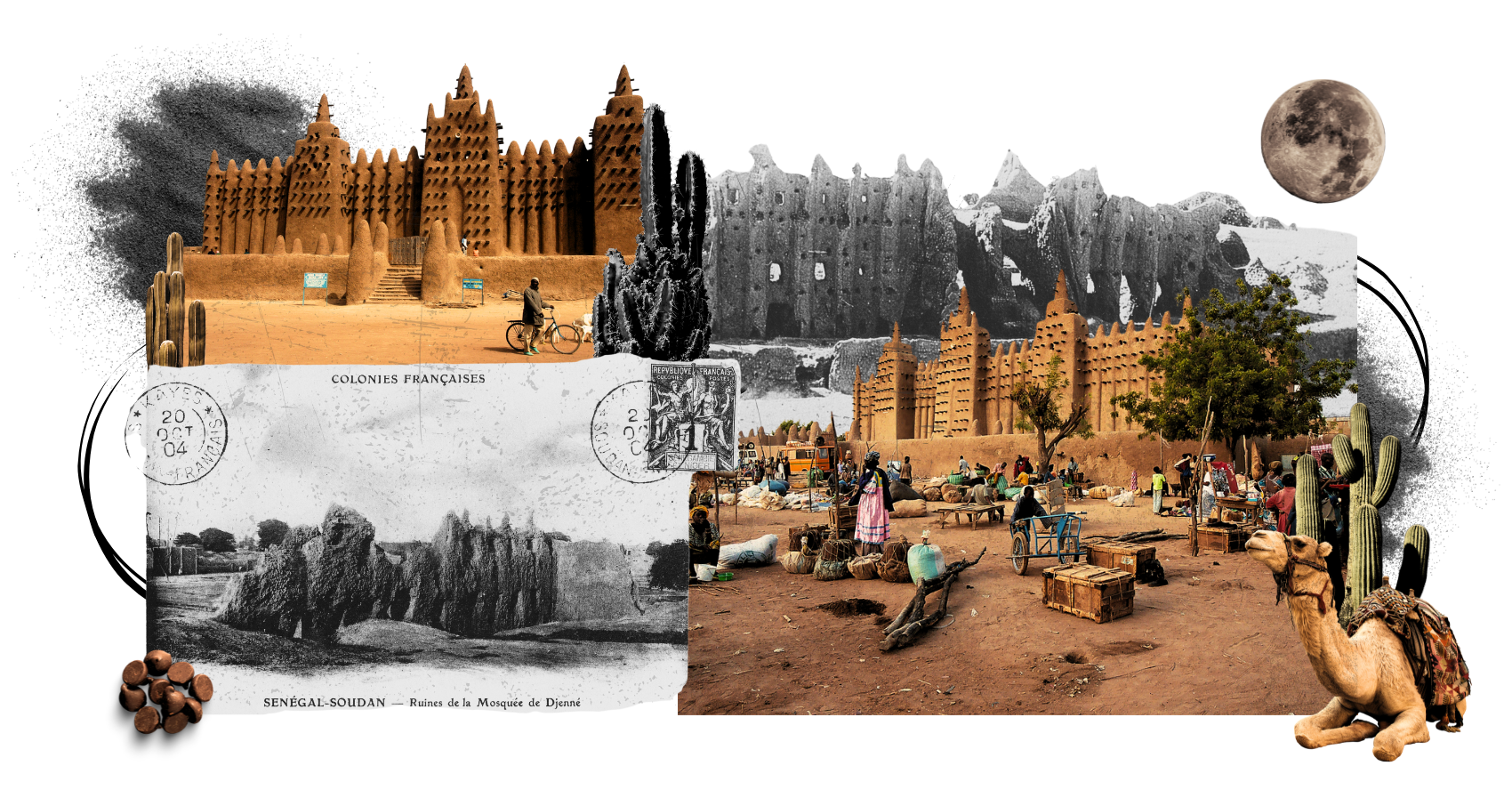

Africans are no strangers to conservationists, preservationists and all manner of experts who call into question Africa’s internal capabilities to safeguard sites and objects of historical value. The Great Mosque of Djenné, its mud-brick walls annually restored by the community, poses a challenge to a Western approach to history which sees preservation as an end in itself, rather than a means to social cohesion.

Editor’s note: This essay is available in our print issue, Demas Nwoko’s Natural Synthesis and the Rise of African Architecture. Buy the issue here.

The Great Mosque of Djenné, located in the Mopti district in central Mali, was built in the 13th century, making it one of the oldest structures on the African continent, let alone the world. Indeed, the town of Djenné is also one of the oldest urban settlements in Africa, with roots back to at least 250 BCE—on par with cities such as Alexandria, Egypt (c. 300s BCE), Benghazi, Libya (c. 500s BCE), and Aksum, Ethiopia (c. 400s BCE).

However, its complex history of being destroyed and then rebuilt during the colonial era poses a challenge to the concept of preservation and history. The scaffolding of the Western epistemological approach to preservation and history is constructed by the ability to describe longevity in a linear, unbroken sequence. By these standards, the genuineness of the mosque’s physical structure is called into question. However, the annual festival of restoring the mud-brick walls, called fête de la crepissage, an ancient, enduring practice, offers a rebuttal. Firstly, the fête de la crepissage directly reflects the long-standing social utility of the mosque and thus rejects its mummification and relegation as an inanimate, inoperative object, much like many of the ritually charged African ‘artefacts’ stored in museums across the world. Secondly, the fête de la crepissage also implies the social utility of history.

In 2000, historian, Adiele Afigbo, delivered a lecture at the Centre for Black and African Arts Civilization in Lagos, entitled ‘The Black Man, History, and Responsibility’. He remarked that ‘by its nature and the way it is practised, history is both science and ideology.’ However, in ‘the final construct,’ history is ‘more often ideology than science especially as it cannot be tested for being true or for the ability to produce any particular effect.’ Nevertheless, he asserts, it is a very important pursuit for it helps to create the environment of empowerment without which nothing can be achieved in the realm of social action.’ Similarly, almost 25 years earlier, historians, J. F. Ade. Ajayi and E. J. Alagoa, tell us in their 1974 article ‘Black Africa: The Historians’ Perspective’, that the purpose of history in pre-colonial African societies, was to ‘provide a sense of continuity,’ for the purposes of explaining to, ‘each person and to each people where they fit into the scheme of things.’ This is important because a person’s ‘self-perception is vital to what [they] do,’ and their self-perception is still ‘largely the result’ of their ‘view of history.’ Note, they assert that the view of history, not simply the recounting of history, is directly related to self-perception and subsequently one’s actions. Such a qualifier is necessary because one, it reveals the human agency required in the processing of history. Two, it also challenges the Western approach to history which displays history as an objective, linear, sequenced recounting of ‘facts’, as its end, rather than understanding history as a social utility, or a means toward self and communal health. If one were to take the former approach, the genuineness of the modern-day Djenné Mosque can never realize its full glory of being one of the oldest world heritage sites. If one takes the latter approach, we find that the continuity which is sought in the name of ‘preservation’ exists among the Malians who actively engage as part of their daily lives, and certainly in the fête de la crepissage...

This essay features in our print issue, ‘Demas Nwoko’s Natural Synthesis and the Rise of African Architecture’, and is available to read for free. Simply register for a Free Pass to continue reading.

Register for a Free Pass

Already a subscriber? Log in.