Photo illustration by Ezinne Osueke / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref: USAID / FLICKR.

THE MINISTRY OF POLITICAL AFFAIRS

Angola’s ‘Inorganic’ Techno-Democracy

Photo illustration by Ezinne Osueke / THE REPUBLIC. Source Ref: USAID / FLICKR.

THE MINISTRY OF POLITICAL AFFAIRS

Angola’s ‘Inorganic’ Techno-Democracy

In 2027, general elections are scheduled to be held in Angola. The forthcoming elections are set to pose a considerable challenge to the political party that has been in power since 1975, the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA). The primary reasons for this are the decline in oil-related revenues and the fact that 66 per cent of the population are under the age of 25. This generation did not experience the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002), and their expectations are not driven by animosity, but rather by a desire for a better life and development. It is noteworthy that since 2008, which marked first elections following the civil war, the MPLA has exhibited a consistent decline, with a decrease of approximately 10 per cent in each subsequent election. The party’s electoral performance is demonstrated by the following percentage of votes received in successive general elections: 81 per cent in 2008, 71 per cent in 2012, 61 per cent in 2017 and 51 per cent in 2022. Should this trend continue, it is forecast that the ruling party will be unsuccessful in the next elections, with a predicted voting share of only 41 per cent.

In this context, the Luanda government is proposing a change to the electoral law, which, it claimed, is intended to make the electoral process more transparent and simpler. However, from the perspective of the main opposition party, União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (UNITA), the proposed changes are a means of accentuating the possibilities of electoral fraud, since they make the monitoring of the process by extra-official or independent bodies more difficult than it already was.

Historically, the process of passing laws was straightforward and adhered to the established procedures of classical representative democracy. The party which holds the majority in the National Assembly (parliament), the MPLA, presented its proposal, which was approved after a period of debate, and the law came into force, with no further discussion. The population demonstrated a limited level of involvement, and for the most part, lacked a comprehensive understanding of the events transpiring, or only possessed a hazy awareness of the situation. The media in Angola conformed to the conventional 20th-century paradigm, characterized by the state’s direct or indirect oversight of television, national radio, and newspapers. This paradigm included TPA (Angola’s public television), Rádio Nacional de Angola and Jornal de Angola. Several outlets were available for the expression of opposition views, including Rádio Despertar, a radio station with relatively limited reach, and private newspapers such as Semanário Angolense, which were frequently acquired by individuals with close ties to the establishment and subsequently ceased publication. It is evident that the opposition had a voice, albeit one that was constrained in its scope. The state wielded significant influence over communication, thereby possessing considerable means of exerting its authority in this domain. The potential for public and published opinion was constrained. Democracy was characterized by formal, representative and parliamentary dimensions, subject to the influence or control of the party in power.

COMMUNICATIONAL CONTROL TRANSFORMATION

At present, a profound transformation is occurring in relation to communicational control and the political intervention of public opinion. To illustrate this point, consider the government’s recent proposed legislative amendments to the electoral law. These legal changes are being met with strong opposition from the public, and this resistance is manifesting not through the conventional channels of democracy, but rather through the utilization of social networks.

The sequence of events commenced in a manner consistent with previous instances: the government submitted its proposal to the National Assembly, and the minister responsible, Adão de Almeida, a well-groomed, cultured and smiling jurist, appeared on television to provide an explanation of the law. After this, however, the situation underwent a reversal. On social networks, members of the opposition, activists, legal professionals and other individuals initiated a widespread movement to repudiate and criticise the law.

The belief is that if the law is passed, it will make electoral monitoring more difficult, because although it is based on apparently correct legal techniques, it creates clear challenges for the main opposition party. This is because it would have to mobilize a huge amount of human and computer resources to monitor the counts at each polling station. The political commentariat has historically regarded the main opposition party, UNITA, as lacking in organization. The simplification of the process, therefore, and the abolition of intermediate procedures and documental synthesis, effectively preclude any possibility of meaningful oversight, rendering the opposition unable to exert credible control over the results.

The internet landscape in Angola is undergoing a period of significant transformation. According to the minister responsible for communications in Angola, Mário de Oliveira, the number of internet users in Angola increased from approximately 6.6 million in 2020 to 12 million in 2024 . The government official cited Angola as an exemplar, noting that the African continent has witnessed a substantial surge in internet users over the past three years, a growth trajectory that has significantly outpaced other regions worldwide. This figure is reasonably similar to the number of voters, although they do not coincide, as a significant proportion of internet users are under the age of 18. It does, however, represent a fairly large population mass where criticism of the government is prevalent, moving away from normal processes and traditional means. The classical channels through which democracy is typically channelled—namely, an assembly of representatives of the people (parliament) and informed by the official media (television, radio and newspapers)—no longer function in the same way.

The exponential increase in the number of users is matched by a significant increase in so-called influencers, in this case, political ones. There are numerous examples of this phenomenon, but let us consider the case of Gangsta77, (an alias of Nelson Adelino Dembo), who created a Facebook page while apparently exiled to South Africa, at least according to his statements, and who has amassed a following of 535,000 individuals. The objective of his social media presence is to incite a non-violent overthrow of the government through the organization of events such as general strikes, ‘panelaços’ (banging pots and pans) and ‘stay-at-home’ protests. These are publicised via his Facebook page, with minimal success in terms of real-world impact, yet substantial virtual support.

It is also important to note that a multitude of individuals, in addition to the aforementioned Gangsta77, employ social networks and digital platforms as instruments to voice their discontent regarding perceived injustices, orchestrate demonstrations, and stimulate discourse on matters of political and social significance. Among the most prominent figures there are Adolfo Campos, a well-known advocate for civic engagement; Gilson da Silva Moreira, known by his artistic moniker Tanaice Neutro, a politically outspoken rapper; Hermenegildo André, popularly called Gildo das Ruas, an activist rooted in grassroots mobilization; Abraão Pedro Santos, widely recognized as Pensador, a commentator on political reform and youth issues; and Laurinda Gouveia, a committed human rights defender and co-founder of a democratic civic movement, have each played significant roles in Angola’s evolving landscape of dissent and activism. These activists have attempted to mobilize civil society, frequently encountering legal challenges in the form of defamation lawsuits, which underscores a salient risk posed by social networks: the delicate balance between freedom of expression and the dissemination of falsehoods and slander. Gouveia has been instrumental in raising awareness among women of their inclusion in the political system and has been a vocal advocate for the participation of women in Angolan politics.

shop the republic

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

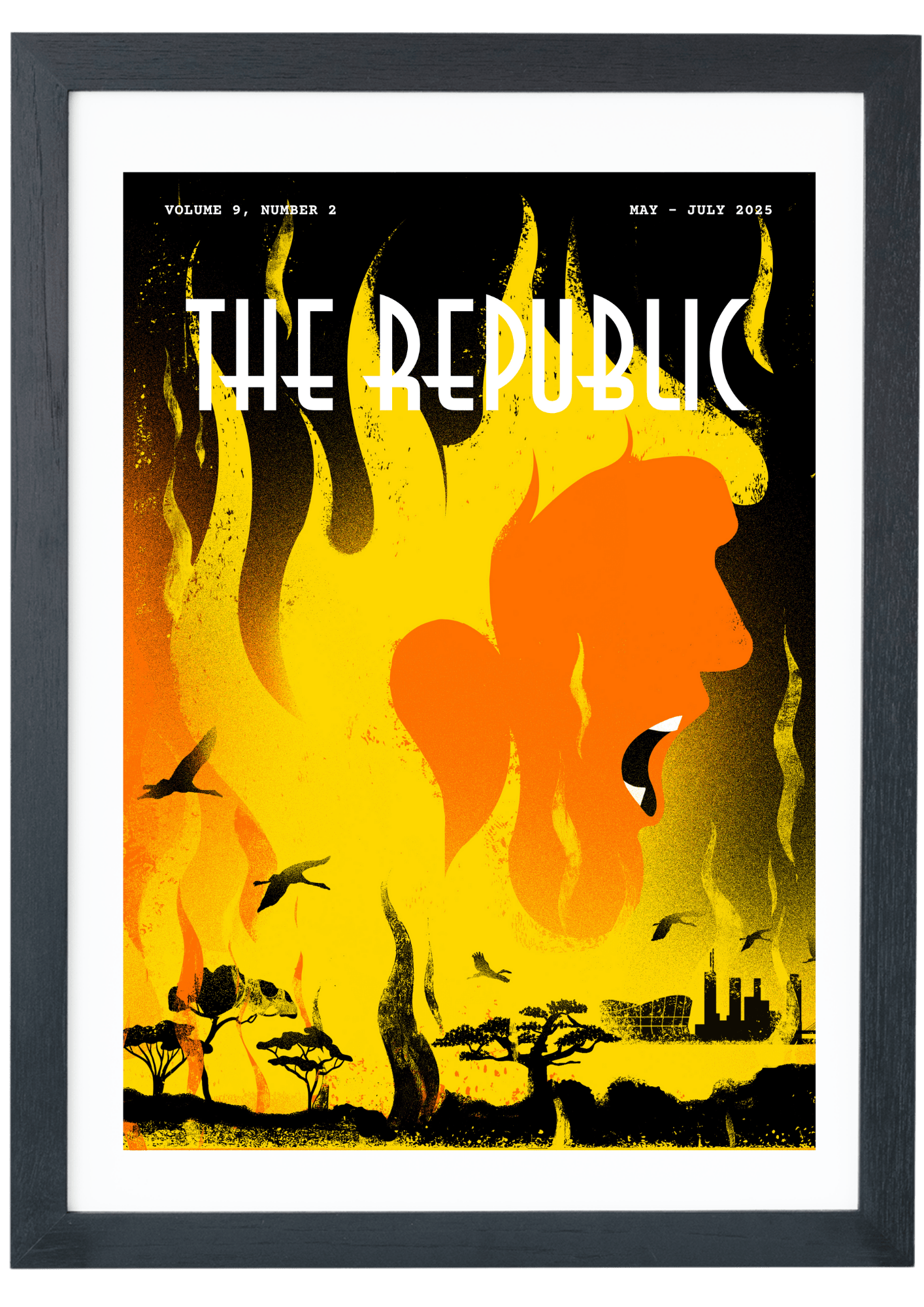

‘Make the World Burn Again’ by Edel Rodriguez by Edel Rodriguez

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

‘Nigerian Theatre’ Print by Shalom Ojo

₦150,000.00 -

‘Natural Synthesis’ Print by Diana Ejaita

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00

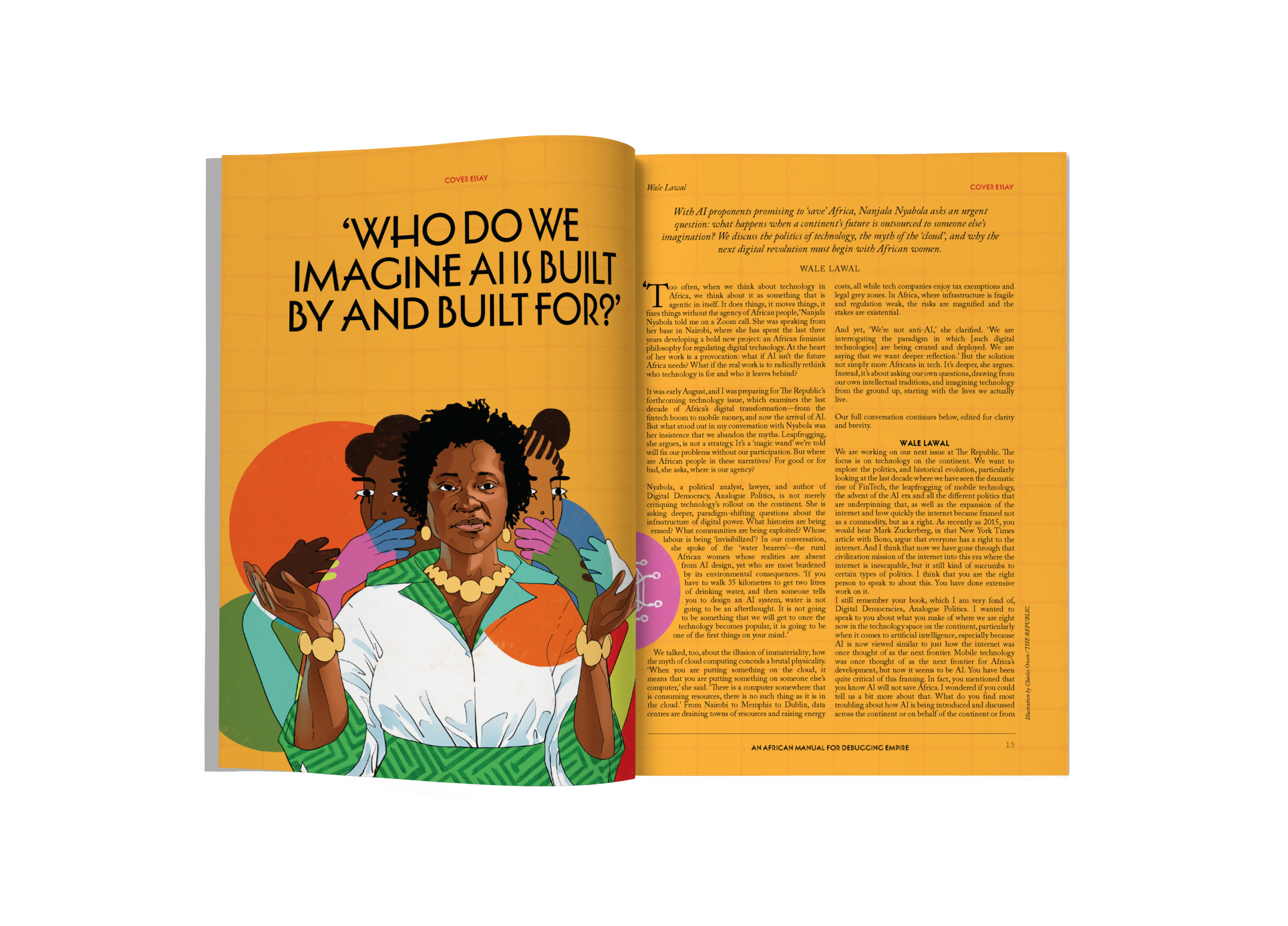

TECHNOLOGY AND GOVERNANCE

However, with greater relevance and impact in the medium and long term, there are entirely digital portals such as Club-K and Maka Angola that play a fundamental role in promoting democracy and freedom of expression in Angola. Both are independent platforms that denounce abuses of power, corruption and human rights violations, offering a space for public debate and raising awareness among civil society. Club-K, under the leadership of José Gama, functions as an information portal that operates as a form of loosely organized platform for news, rumours and speculation. The value of the website lies in its role as a space of freedom, although the veracity of the information published on it is not always easily confirmed. Nevertheless, the site has proven to be a fundamental instrument for activists and journalists seeking to disseminate information that does not find space in the traditional Angolan media.

Maka Angola, established by journalist and activist Rafael Marques (where I am a legal analyst), is a platform dedicated to defending human rights and combating corruption. The site has been a pivotal platform for highlighting national irregularities, encompassing instances of illicit resource exploitation and political repression. Additionally, it has been instrumental in promoting legal awareness and fundamental rights. Marques, through Maka Angola, has already been subject to legal proceedings in relation to his investigations. Yet, he continues to be an active voice in the defence of freedom of expression. Maka Angola was recently awarded the Press Freedom Merit Award, a distinction bestowed by the Angola Union of Journalists and the Media Institute of Southern Africa, Angola.

These actions demonstrate the impact of these platforms in defending fundamental rights and building a more democratic society. These are merely a small sample of the numerous illustrations of a novel panorama that is emerging in Angola.

shop the republic

In Angola, the intersection between technology and governance is shaping an unconventional democratic landscape, one that is arising spontaneously and outside of traditional political structures. While the government has historically relied on conventional means to maintain control, the rapid proliferation of digital platforms, social networks and encrypted communications is enabling civic engagement that is not subject to state oversight. Consequently, the advent of technological innovation has given rise to an ‘inorganic’ democracy, characterised by the presence of decentralized information networks, popular mobilization, and alternative spheres of political discourse. This technological innovation is spreading at an accelerated rate and has profoundly transformed the dynamics of the Angolan political system. The resulting model is ‘inorganic’—a political structure that is less dependent on traditional institutions and more shaped by decentralized information networks, grassroots mobilizations and alternative spaces for political discourse.

Angola is currently undergoing this phenomenon with great intensity. According to data from Afrobarometer (2025), a mere 24.2 per cent of respondents consider the traditional press in Angola to be completely free. Moreover, 30.9 per cent of respondents indicated that they never obtain their news from television, while 66.8 per cent never get their news from print newspapers. Furthermore, 33.1 per cent of respondents reported accessing news via Facebook and other social networks on a daily basis, with this figure rising to 43 per cent among those who access news several times a week.

It is indisputable that with the progression of the internet and social networks, the dissemination of information has transitioned from being exclusively governed by government institutions to a more diverse and decentralised landscape. In the contemporary era, the advent of digital technologies has empowered ordinary citizens to produce and disseminate political content, thereby exposing problems, denouncing abuses and promoting wide-ranging discussions on issues that were previously the preserve of elites. The decentralization of information has been demonstrated to engender a greater diversity of narratives and to reduce the monopoly of official versions, thus rendering information more inclusive and dynamic. Another aspect of inorganic democracy fostered by technology is the creation of alternative spheres of political discourse. Independent websites, podcasts and YouTube channels offer critical analysis of governments and public policies, often acting as a counterpoint to traditional narratives. These platforms not only provide a medium for previously marginalised sectors of society to articulate their concerns but also foster a more open and pluralistic environment for debate.

However, a significant proportion of activism remains confined to the sofa and the virtual realm. Frequently, an initiative that is lauded by thousands of individuals via social media, particularly those involving public acts, sit-ins, strikes or ‘staying at home’, yields no tangible outcomes in the real world. Recently, an appeal by Gangsta77 for people to remain at home on a designated day was met with significant indifference, despite the considerable support the initiative received online.

In addition to this discrepancy between the virtual and real worlds, this model of ‘inorganic’ democracy also faces challenges that have been observed in Angola. The decentralization of information has been demonstrated to result in the propagation of disinformation and political polarization, thereby hindering the establishment of a consensus. This phenomenon is particularly salient in the present moment, as public opinion has become excessively radicalized. Information technologies, in particular social networks and recommendation algorithms, have been demonstrated to play a significant role in amplifying radicalization and excessive polarization. These systems tend to generate information bubbles, where users are exposed exclusively to content that serves to reinforce their pre-existing views, thereby hindering access to perspectives that may challenge these views. Furthermore, the logic of digital engagement appears to favour content of an extreme and emotionally charged nature, as this generates a greater level of interaction, which in turn drives inflammatory discourse and results in societal fragmentation. Such a phenomenon is observable in Angola, where the primary opposition party is confronted with a movement on social media that accuses it of being lax and incapable of opposition, and which calls for opposition that, at times, assumes violent forms.

shop the republic

In the absence of effective regulatory frameworks and digital literacy skills, the mobilizing potential of information technologies can be exploited to undermine established regimes and promote anarchic agendas. The challenge, therefore, is to find a balance between freedom of expression and the control of digital abuses, ensuring that technology is an ally of democratic evolution and not a tool for its destruction.

This has prompted the Angolan government to introduce a bill to regulate fake news. The government has defended the project, citing the necessity for enhanced oversight of information disseminated to the public. This is purportedly aimed at counteracting the manipulation of public opinion and ensuring more transparent communication. However, this initiative was met with suspicion by various sectors of society, who viewed it as a potential instrument of state censorship, with the capability to limit freedom of expression and the right to information.

The response from civil society was precipitated by the campaign led by the Maka Angola portal. The platform issued a warning regarding the potential dangers of legislation that could be utilized to silence dissenting voices under the pretext of combating fake news. In the ensuing discourse, a plethora of organizations, intellectuals and citizens swiftly participated, articulating apprehensions regarding the potential imposition of arbitrary restrictions on the independent press and the right to public demonstration.

The proposal to regulate fake news in Angola has thus become an emblematic example of the tension between information security and democratic rights, raising a crucial debate about the limits and risks of state intervention in communication.

It is evident that the Angolan government has utilized technological advancements to oversee and regulate individuals deemed as dissidents. This demonstrates that while digital innovation possesses considerable potency, it does not inherently ensure the promotion of political liberty.

Notwithstanding the aforementioned limitations and challenges, technology is visibly affecting a transformation in the Angolan democratic landscape, manifesting as a malleable and dynamic form of democracy. This emergent paradigm entails an augmentation in the civic engagement of the population, thereby empowering them to engage more proactively in the political discourse and the advocacy for their rights. This model is predicated on a digitally literate and engaged citizenry, adept at navigating the opportunities and challenges posed by the digital age to contemporary governance. But until critically evaluated, Angola’s ‘inorganic’ democracy remains an untested experiment, its ability to foster genuine political engagement still uncertain⎈

BUY THE MAGAZINE AND/OR THE COVER

-

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Republic V9, N3 An African Manual for Debugging Empire

₦40,000.00

US$49.99