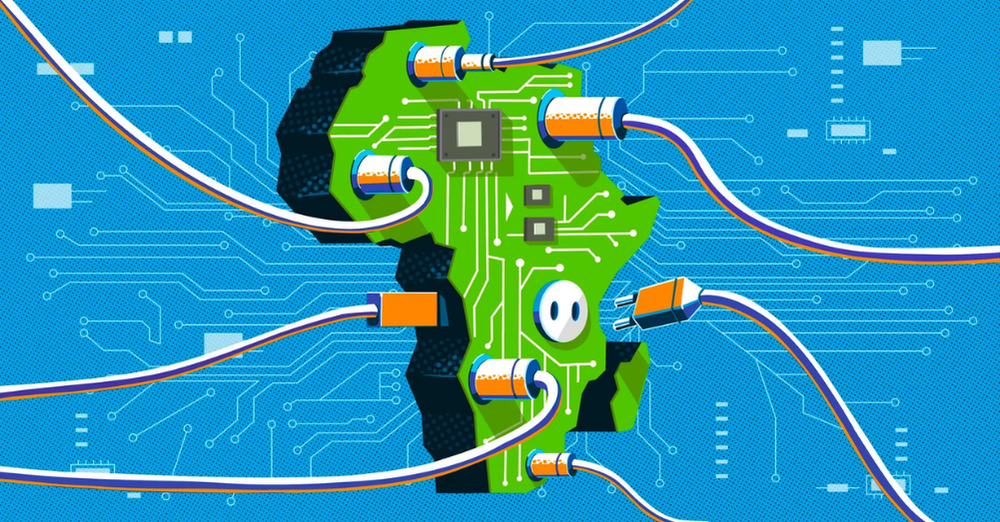

How Technology Preserves the Legacy of Colonialism Across Africa

The parallels between colonialism and bias in modern technology offer an instructive analysis that reveals how contemporary digital infrastructures perpetuate colonial power even as they claim to connect the world and advance social justice issues.

Editor’s note: This essay is available in our print issue, An African Manual for Debugging Empire. Buy the issue here.

Silicon Valley is globally acclaimed for its pivotal role in shaping the fourth industrial revolution. However, its gleaming innovations obscure the troubling reality that the Valley is a thriving habitat for the racist, sexist, white nationalist and hyper-capitalist culture that has long shaped human history. Thanks to the influence of globalization, technologies midwifed in Silicon Valley become global exports that diffuse their ideological baggage globally.

As writer and critic, Amiri Baraka posited decades ago in his seminal work, Technology and Ethos, machines, ‘are an extension of their inventor-creators.’ They are infused with and project their inventors' values, ethics, mores and worldviews. Technology, in other words, is never neutral. Even the choice of what problems to solve or which features to build is value-laden. As the ideological alignment of the creator becomes the default that everyone else uses.

For instance, the absence of non-white human characters and lack of skin-colour diversity in early emoji sets subtly communicated a default human that erased non-white identities and privileged whiteness. Since most tech-company employees and executives are white and non-disabled, it’s no surprise that technology products and services default to a white, able-bodied perspective...

This essay features in our print issue, ‘An African Manual for Debugging Empire’. To continue reading this article, Subscribe.

Already a subscriber? Log in.