Illustration by Diana Ejaita. / THE REPUBLIC.

EDITOR’S FOREWORD

On Demas Nwoko

Illustration by Diana Ejaita. / THE REPUBLIC.

EDITOR’S FOREWORD

On Demas Nwoko

Demas Nwoko did not coin the term, ‘Natural Synthesis’. That was the illustrator, Uche Okeke. However, Nwoko, along with Okeke and several other artists affiliated with the Art Department of the Nigerian College of Art, Science and Technology, in Zaria—a movement eventually known as the ‘Zaria Art Society’ or the ‘Zaria Rebels’—pioneered the post-colonial art paradigm around the 1960s. According to Princeton’s Chika Okeke-Agulu, an artist practising Natural Synthesis, as conceived by the Zaria Rebels, typically ‘studies an art form indigenous to his ethnicity and reformulates a modernistic aesthetic and formal style on the basis of that art.’ In his 2006 essay, ‘Nationalism and the Rhetoric of Modernism in Nigeria: The Art of Uche Okeke and Demas Nwoko’, (where the foregoing quote is from) Okeke-Agulu found Nwoko to be a step unconventional. According to Okeke-Agulu, despite being Igbo and thus a southerner, Nwoko’s ‘most important work at the time was informed by his research into Nok sculpture from the north-central region of Nigeria.’ Nwoko’s artistic philosophy was not caged by ethnic lines, and though he had a national outlook, his nationalism did not manifest in the floaty or jingoist sense the independence era often commanded. It was local, embedded, curious and informed by its immediate environment—more importantly, it served a specific need and function.

No surprise then that despite being from Delta State, Nwoko set up the New Culture Studio in Ibadan. In my interview with him, which features in this issue, he tells me how the hilltop complex began as an art studio he built for himself while teaching at the University of Ibadan. He explained how, over the years, the building evolved in a Malthusian way out of necessity. In August 2024, during our inaugural Alternative Heritage Programme (developed in collaboration with StoryMi Academy and the French Embassy in Nigeria), the New Culture Studio was one of our stops. As Rufus Nwoko, the director of the studio and Nwoko’s grandson, gave us a tour of the building, we observed, just as Okeke-Agulu did in 2006, how Nwoko brought an innovative perspective to Nigerian and, by extension, African modernism.

Later this year in December, Nwoko will turn 90. It was only natural that ahead of this milestone, we invited authors to ruminate on one of Nigeria’s leading champions of Alternative Heritage. The stories in this issue celebrate, interrogate and reflect on Nwoko’s artistic contributions, his influence and his legacy, while bearing critical witness to the global rise of African architecture and design and Nwoko’s role in it.

My continued thanks to everyone who supported and contributed to this issue: Sophie Bouillon of StoryMi, Emmanuelle Harang of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Quintin Leeds of XXI Magazine and Rufus Nwoko, for his insightful tour of the New Culture Studio and his support with our Demas Nwoko interview. This issue is the second of the two magazines we have developed under the Alternative Heritage Programme, and I am excited to share it with you.

Now, the stories.

‘Nigeria doesn’t happen to me; I happen to Nigeria,’ Nwoko told me during our interview. In November 2024, I had the opportunity to speak with Nwoko, who turns 90 this year, about his thoughts on art, architecture and design. We also reflected on his career, philosophy and the lasting impact he has had on African architecture and design. According to him, ‘African art lends itself to social commentary, because African art is very expressive. It is very eloquent. It talks to its beholder. It talks to its audience very easily. That is why I am in love with African art, and that is how I practise.’

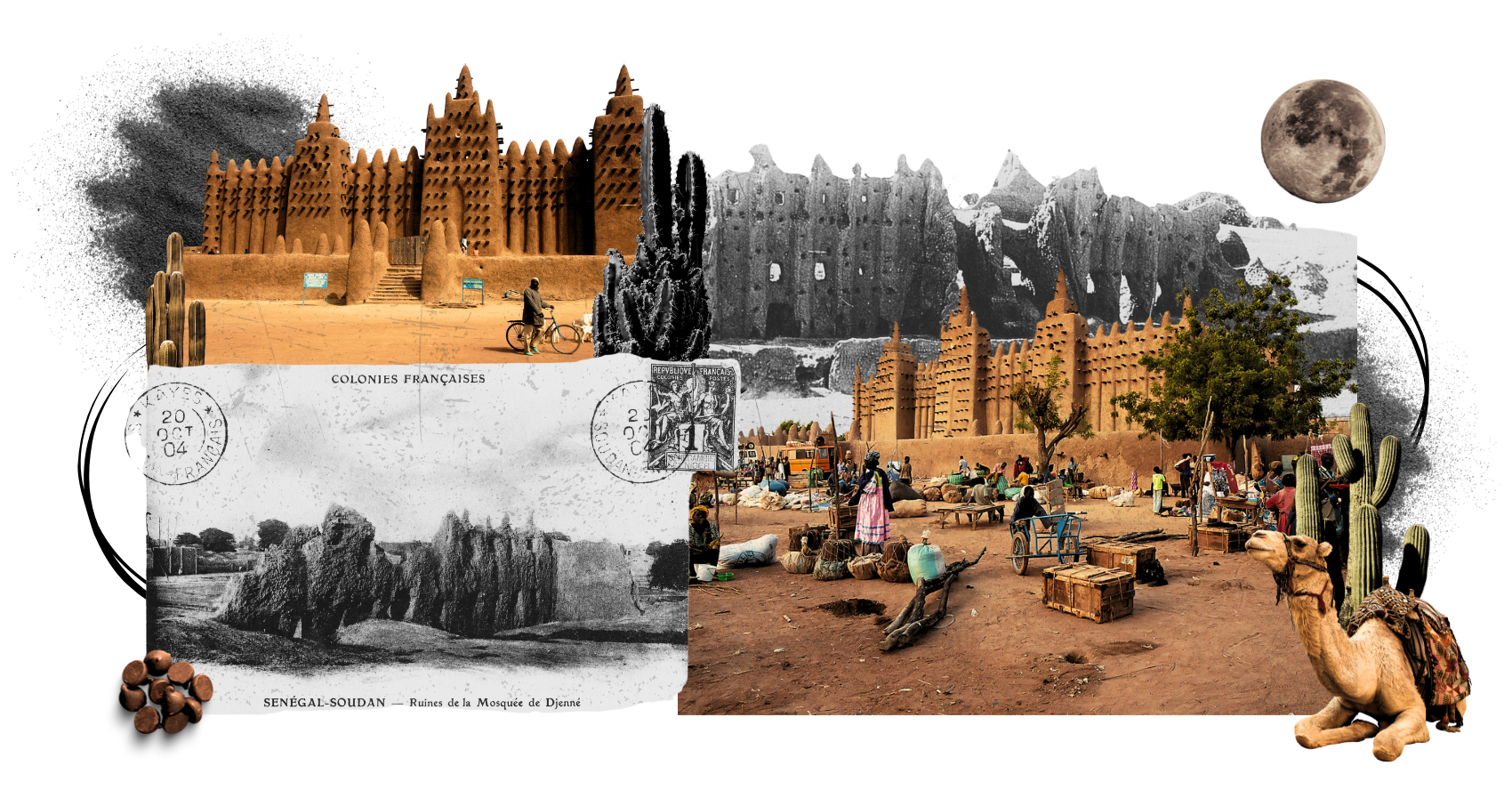

‘The Great Mosque of Djenné, located in the Mopti district in central Mali, was built in the thirteenth century, making it one of the oldest structures on the African continent,’ Kai Mora writes, considering the historical significance of the monument. ‘However, its complex history of being destroyed and then rebuilt during the colonial era poses a challenge to the concept of preservation and history,’ she continues. ‘Its mud-brick walls, annually restored by the community, poses a challenge to a Western approach to history which sees preservation as an end in itself, rather than a means to social cohesion.’

‘600 million people are expected to migrate to African cities by 2050, which means narratives come a distant second to basic shelter,’ Delela Ndlela writes. ‘Governments, the private sector and citizens alike will need to rise to the challenge of creating sustainable, healthy and affordable housing,’ she continues. ‘New African architecture cannot afford to replicate the mistakes of the last three centuries, we cannot afford architecture ideated in the ivory tower and subsequently stamped onto the landscape. We need a post-stylistic architecture, the architecture of here and now,’ Ndlela cautions.

‘Who Do We Imagine AI Is Built By and Built For?’

With AI proponents promising to ‘save’ Africa, Nanjala Nyabola asks an urgent question: what happens when a continent’s future is outsourced to someone else’s imagination? We discuss the politics of technology, the myth of the ‘cloud’, and why the next digital revolution must begin with African women.

We Need New African Architecture

With 600 million people expected to migrate to African cities by 2050, Africa must rethink its architecture as existing approaches have proven inadequate.

The Great Mosque of Djenné And the Social Utility of History

Africans are no strangers to conservationists, preservationists and all manner of experts who call into question Africa’s internal capabilities to safeguard sites and objects of historical value. The Great Mosque...

This issue also features authors writing on topics ranging from Arts & Culture to World Affairs. In our Arts section, culture writer, Emmanuel Esomnofu, explores the overlooked legacy of the late Nigerian musician, Sonny Okosun, in a compelling music profile. According to Esomnofu, ‘Sonny Okosun portends a greater lesson on the risk of erasure. Undoubtedly great and touching base with a lot of the great musicians of his time, that his profile does not resonate strongly in the cultural landscape further reveals something about the African consciousness.’

This section also features an essay by Republic junior editor, Ijapa O, examining the current state of Nigerian theatre and its future prospects. According to O, ‘Where before theatre companies travelled all over the country to perform for audiences, they now preferred to record their plays and broadcast them on television, an innovation that quickly caught on.’

Additionally, Ukamaka Olisakwe profiles the pioneering Nigerian writer, Flora Nwapa, who dedicated her life to writing in a period where women writing and publishing works were not accorded the same respect as men. Rereading Nwapa’s Efuru after two decades, Olisakwe writes that, ‘it was as if I was discovering the novel for the first time and so was struck by the clean pragmatism of its themes, the compelling lives and the richly drawn family dynamics and relationships, how the women of this world were constantly colliding with or complementing each other.’

Sonny Okosun and the Paradox of Nigerian Greatness

Sonny Okosun was one of the most beloved artists of his time. However, the singer’s gentle perspective has not always favoured his legacy, hinting at a deeper cultural and societal...

Towards a True Nigerian Theatre

As the production and consumption of theatre in Nigeria declines, experts weigh in on its current status and what the future holds.

A Woman among Women

Flora Nwapa dedicated her life to writing in a period where women writing and publishing were not accorded the same respect as men. This resistance is reflected in her characters,...

In Climate Change & the Environment, Ancci writes on the work of Burkinabé-German architect, Diébédo Francis Kéré, as he champions the use of local materials to build sustainable housing. For someone who comes from such extreme weather, a national reality grappling with high levels of poverty, and a village with no schools, electricity or clean drinking water, Ancci writes, ‘Kéré’s mission as a trained architect was … to build schools that inspire both the community and the students about the possibilities that abound in their small community as well as in the locally sourced materials they think so little of.’

In recent years, Lagos has witnessed a surge in waterfront developments, mirroring the urban landscapes of cities like Miami and Los Angeles. In her essay, Dawn Chinagorom-Abiakalam writes on contemporary urbanization and the luxury apartment complex in Lagos. ‘The Lagos living experience now seeks to provide a shielded experience for the rich, while ignoring the needs of the lower-income citizenry who make up more than 60 per cent of Nigeria,’ Chinagorom-Abiakalam explains. ‘Rather than fostering inclusive growth, these developments have intensified socio-spatial inequality while increasing climate vulnerabilities, such as rising sea levels and increased inner-city flooding.’

The Luxury Apartment Complex in Lagos

In recent years, Lagos has witnessed a surge in waterfront developments, mirroring the urban landscapes of cities like Miami and Los Angeles. Rather than fostering inclusive growth, these developments have...

Francis Kéré’s Revolutionary Slingshot Towards Architectural Sustainability

Community engagement is central to the work of Burkinabé-German architect, Diébédo Francis Kéré, as he champions the use of local materials to build sustainable housing.

In Culture, Alternative Heritage participant and photographer, Aleruchi Kinika, brings the intricate cultures of wrapper tying and wrapper wearing in Rivers State to life in her Wrappers of Rivers photography series. Kinika shares her approach, explaining that through her photography, she ‘wanted to tell the story of the wrappers and Rivers people as one.’

Until the mid-twentieth century, Yoruba people lived in ‘agbo ilé’—a conjugation of houses that formed what Leo Frobenius described as ‘astonishingly large compounds’. In his essay, Ernest Ògúnyemí explores the expressive dimensions of Yoruba architecture. According to Ògúnyemí, ‘While the form of Yoruba architecture changed, it is remarkable that the idea of the agbo ilé (the feeling attached to it) did not go away. Sadly, today, many of us live quite remote from the indigenous and the evolved forms, and even more remotely from the feeling at the heart of their metaphoric expressions.’

The Expressive Dimensions of Yoruba Architecture

While the form of Yoruba architecture has changed, the idea of the agbo ilé has not gone away.

Wrappers of Rivers

In documenting and displaying the intricate cultures of wrapper tying and wrapper wearing in Rivers State, Aleruchi Kinika, the photographer behind the series, ‘Wrappers of Rivers’, says she ‘wanted to...

In Gender, Alternative Heritage participant, Emmanuel Azubuike, explores woman-woman marriage in south-east Nigeria, focusing on Angela, for whom marrying another woman provided the best culturally accepted alternative to having her own offspring. ‘I married a wife into my husband’s home because I do not have my own child. It is important that a woman marries another if she does not have her own offspring,’ Angela told Azubuike.

In History, Alternative Heritage participant and photographer, Olaoluwa Olowu, writes on the history of the Yorubas in Ghana. At the heart of this connection is Chief Brimah, an Ilorin merchant, whose leadership and entrepreneurial spirit forged enduring bonds with the Ga people and deeply influenced Accra’s Zongo communities.

The Yorubas of Ghana

The historic migration of the Yoruba people from Ile-Ife has shaped Ghana’s Yoruba community through trade, faith and family ties. At the heart of this connection is Chief Brimah, an...

The Woman Who Married a Woman in Igboland

In a culture that reveres procreation, and where boys are considered more valuable than girls, what happens when a woman marries another woman to fulfil her societal obligation of childbearing?

In Interviews, Nigerian architect and designer, Tosin Oshinowo, says we must ‘rethink architecture’, not just in terms of design, ‘but also in how we live, build, and develop materials that are suited to our environment. In Africa, we are still in the early stages of this shift, but it is exciting to see more practitioners, including ourselves, beginning to explore new approaches to sustainable architecture.’

‘We Must Rethink Architecture’ Tosin Oshinowo’s First Draft

Nigerian architect and designer, Tosin Oshinowo, believes that, now more than ever, the growing awareness of the climate crisis makes it imperative for architects to rethink building practices: ‘The next generation of practitioners will likely be better equipped than mine, as sustainability is now a fundamental part of their training and practice. With the right encouragement, we can expect to see meaningful change.’

In World Affairs, Lutivini Majanja examines the fate of East African men conscripted into the British Carrier Corps during the First World War, drawing from the experiences of her maternal great-grandfathers. While one of her great-grandfathers, Chivutionyi, evaded forced conscription, her other great-grandfather, Odanga, fought in the First World War—‘he is still fighting.’

From Uganda, Hadijjah Sebunya examines works in Kampala that embody the philosophy that profoundly influenced Demas Nwoko. The three buildings—the Kamwokya Community Centre, the Japanese Yamasen and the pre-colonial UNESCO heritage site, the Kasubi Tombs—have each addressed Kampala’s challenges in distinct ways. According to Sebunya, ‘All of these buildings would be embraced by the Zaria rebel society and in their own way meet the philosophy of Nwoko.’

Kampala by Design

Demas Nwoko’s design philosophy stressed the importance of beauty and significant sustainability, a message that travelled beyond Nigeria to Kampala, Uganda.

Odanga Is Still Fighting

My maternal great-grandfathers were both directly affected by the First World War. Only one of them lived to tell his story.

In 2024, The Republic announced funding from the Open Society Foundations (OSF), which will go into developing a network of universities in Nigeria. We also announced funding from the Mellon Foundation, which will support the expansion of our editorial work across multiple formats. Since our last issue, we have also received funding from the JournalismAI Innovation Challenge supported by the Google News Initiative. This issue is our first of 2025, and we’re excited to welcome you into the new year!

As usual, we encourage our readers to engage with our essays and articles, and to provide insightful comments. Readers may send their views directly to the editor by addressing emails (of no more than 700 words) to wale@republic.com.ng, with the subject, ‘Comment on Xyz Essay’, or ‘Letter to the Editor’ as applies. Comments and letters will be archived and, depending on the quality of the arguments presented, we may reach out to assist in developing your letters and comments further for publishing in the magazine.

At The Republic, we will always prioritize the meaningful exchange of ideas. We commit to pressing forward: on the most critical of social, political and economic issues; by innovating through knowledge gaps; and by providing guidance through thickets of opinion, ignorance and misinformation—three key features of our time—in search of glades of insight⎈

shop the republic

-

Looking For Ken Saro-Wiwa A Live Listening Event / Season 2 of The Republic Podcast

£20.00 -

‘The Empire Hacks Back’ by Olalekan Jeyifous by Olalekan Jeyifous

₦70,000.00 – ₦75,000.00Price range: ₦70,000.00 through ₦75,000.00 -

The Republic V9, N3 An African Manual for Debugging Empire

₦40,000.00

US$49.99